Matt Walsh details the mind blowing systemic racism of the DEI hiring practices of the FAA. (Hat-Tip to The Renegade Institute for Liberty at Bakersfield College – FB Page)

Matt Walsh

Peter Doocy Serves KJP Some Cannibal Tartare (#CannibalGate)

I was amazed at Karine Jean-Pierre’s (KJP) response to Doocy. She said that Biden lying was fine because it was an emotional moment.

What!?

See RED STATE for more of Biden’s ?-?

Per Jesse Watters below, the “fact checks” were out n “full force”

- “[Biden] off on details” – AP

- “Biden mischaracterizes” – NBC

- “Biden’s claim differs” – CNN

- “Lol” – RPT

JESSE WATTERS

Could you imagine if Trump “mischaracterized” a story like that? Oh-my-goodness.. the 24-hour news cycle would b cray-cray.

Here is Peter Doocey’s after thoughts:

MATT WALSH

Joe Biden invented a story about his uncle being eaten by cannibals. Unsurprisingly, he’s now being accused of cultural insensitivity for it.

FOX & FRIENDS

F&F discuss a few lies from Biden

Google Gemini AI Story Gets Worse | Matt Walsh

Today on the Matt Walsh Show, you might think the story of Google’s woke dystopian AI program can’t get any worse, but it has. I’ll explain. Also, the media claims that conservatives at CPAC are plotting the end of democracy. A pundit on MSNBC inadvertently claims that America is a fundamentally christian nationalist country. The Left freaks out after a court in Alabama grants personhood rights to human embryos. And Kristen Stewart is on a press tour and she really wants you to know that she’s gay. Why do we need to know this? and why is she wearing a mullet?

Our “A.I. Overlords” Are Racist! (Plus Some RPT Creations)

The first 20-minutes is about the A.I. issue and Google pausing it’s use of Gemini. Elon Musk re-Tweeted (re-Xed?) an isolated portion of this on X.

Today on the Matt Walsh Show, Google’s new AI program just launched this week and it’s already attempting to erase white people from history. Our woke dystopian future has arrived. Also, the Biden Administration tries to buy more votes with yet another “student loan forgiveness” scheme. A major cellular outage affects thousands of Americans. Is there something sinister behind it? And the National MS Society fires a 90 year old volunteer for failing to put her pronouns in her bio. It sounds like a Babylon Bee headline but it’s real.

Ep.1318

More from RED STATE:

Perhaps you saw the news about Google’s “Gemini.” It’s an AI bot that you can speak with that generates images on command.

However, as you can probably guess, the AI is incredibly leftist thanks to its programmers. You’ve probably seen some of the people who attempted to create pictures of medieval knights and Vikings only to have the bot spit back images of every race and gender under the sun except for a white person.

If you speak to Gemini, the bot will give you every excuse under the sun as to why it can’t generate images of white people on demand including the idea that it doesn’t want to generate “harmful stereotypes.” In fact, as one user pointed out, asking it to generate an image of a “white family” will make it refuse in order to ensure “fairness and non-discrimination.” However, asking it to generate a black family will cause it to deliver exactly as asked.

An AI is only as racist as its programmer, and sure enough, its programmer is pretty racist.

Jack Krawczyk is the product lead at Gemini. When it was pretty clear the AI was being racist, people began looking into Krawczyk’s posting history on X, and, sure enough, what was dug up was a mess of anti-white sentiment and social justice blabber.

- “White privilege is f**king real,” posted Krawczyk in 2018. “Don’t be an a**hole and act guilty about it — do your part in recognizing bias at all levels of egregious.”

As Krawczyk has now protected his tweets, the only way to access them is screenshots taken by X users who dug through his history.

So I have seen the Pope ones. The American Founders ones… but these take the cake!

Apparently white people never existed according to Google AI. #AI #GoogleAI #google #googlegemini pic.twitter.com/PjIG83q72t

— Noctis Draven (@DravenNoctis) February 22, 2024

I CREATED ONE (by edit)

Why Self-Esteem Is Self-Defeating (Myths of Psychology)

(Originally posted Sept 2017, updated Aug 2023)

- “There is no correlation between goodness and high self-esteem. But there is a correlation between criminality and high self-esteem. … Yes, people with high self-esteem are the ones most prone to violence.”

Is having high self-esteem key to happiness? That’s what children are told. But is it true? Or can that advice be doing more harm than good? Author and columnist Matt Walsh explains.

I am updating the original “simple” post with the below. What is the below? It is an expansion of the idea of Self-Esteem and the powers the Lefty educators try to embed in it’s fruits and goals/meaning. As with anything the Left touches, it destroys [speaking here of education], they also distort meaning of words and concepts beyond their useful parlance and application. What follows are forum discussions for an accelerated Masters degree in Education. (A friend had to go on a baseball trip with the high school team and had to take a break from his studies. I filled in.) While class was on “multicultural literature for the classroom,” in the class discussion forum there was a discussion on self-esteem which I jumped in to.

I posted the following knowing I would be the only person with ideas like this — “evolved” further along the thought process with resources foreign to most in the field chasing a degree. I will add two responses I got with added thoughts and resources for my readers. For Context, THIS PDF was one of my papers for this class… it was during the writing of this paper that “self-esteem” was being discussed.

SELF-ESTEEM

I have heard (read) a few here mention the importance of self-esteem. In studies done on inmates (drug-dealers and rapists), self-esteem was high.

I think we as educators should be careful not to try and build self-esteem. First, we do not have the right credentials to know or diagnose true self-esteem. Secondly, the type that seems to pervade definitions today is the type that hinders the kids in academics. I read an interesting book some years ago, and I would suggest everyone here gets it at some point during his or her journey to teach, and teach well. The book is entitled The Conspiracy of Ignorance: The Failure of American Public Schools, by Martin Gross. I wish to quote a bit from a section on self-esteem:

- “A large group of eager American 8th graders from two hundred schools coast-to-coast were excited about pitting their math skills against youngsters from several other nations.

- “The math bee included 24,000 thirteen-year-olds from America, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Spain, Ireland, and four Canadian provinces, all chosen at random and given the same 63-question exam in their native language.

- “It was a formidable contest, and the American kids felt primed and ready to show off their mathematical stuff. In addition to the math queries, all the students were asked to fill out a yes-no response to the simple statement “I am good at math.”

- “With typical American confidence, even bravado, our kids responded as their teachers would have hoped. Buoyed up by the constant ego building in school, two-thirds of the American kids answered yes. The emphasis on “self-esteem” – which permeates American schoolhouses – was apparently ready to pay off.

- “Meanwhile, one of their adversaries, the South Korean youngsters, were more guarded about their skills, perhaps to the point where their self-esteem was jeopardized. Only one-fourth of these young math students answered yes to the same query on competence.

- “Then the test began in earnest. Many of the questions were quite simple, even for 8th graders. One multiple-choice query asked: ‘here are the ages of five children: 13, 8, 6, 4, 4. What is the average age of these children?’ Even adults, long out of the classroom, would have no trouble with that one. You merely add up the numbers and divide by 5. The answer, and average age of 7, was one of the printed choices.

- “How did the confident American kids do on that no-brainer, on which we would expect a near-100 percent correct response? The result was ego-piercing. Sixty percent of our youngsters got it wrong.

- “When the overall test results came in, the Americans were shocked. Their team came in last, while the South Koreans won the contest. The most interesting equation was one of paradox. The math scores were in inverse ratio to the self-esteem responses. The Americans lost in math while they vanquished their opponents in self-confidence. The South Koreans, on the other hand, lost the esteem contest, but won the coveted math prize.” (pp.1-2)

An article by one of my favorite authors Paul Vitz, who is Professor Emeritus of Psychology, Department of Psychology, New York University and Adjunct Professor, John Paul II Institute for Marriage and Family, Washington, D.C. can be found at:

I hope this refocuses us to zero in on what truly makes a person (child) succeed.

- A 1989 study of mathematical skills compared students in eight different countries. American students ranked lowest in mathematical competence and Korean students ranked highest. But the researchers also asked students to rate how good they were at mathematics. The Americans ranked highest in self-judged mathematical ability, while the Koreans ranked lowest. Mathematical self-esteem had an inverse relation to mathematical accomplishment! This is certainly an example of a “feel-good” psychology, keeping students from an accurate perception of reality. The self-esteem theory predicts that only those who feel good about themselves will do well — which is supposedly why all students need self-esteem — but in fact feeling good about yourself may simply make you over-confident, narcissistic, and unable to work hard. (Paul Vitz)

I wish I had kept the original engagements written to me from Rachel, and Jodi. Unfortunately all I have are my responses — so context will be tough, but out of these responses and my additions there will be usable material for the religio-political apologist. First up is Rachel

Hi Rachel,

Did you read those articles I posted in my main post and other responses? What are your thoughts on those articles? I will give you another one to read that may address some of your worries about self-esteem. http://www.cyc-net.org/today2002/today020208.html (Trying to track down the article… will update when I find it.)

Unfortunately, you make my point when you say

- “What do these kids have high self esteem about? Living below poverty levels? Typically, being abandoned by one or both parents? Having society in general believe that they will never succeed at anything? Having the life expectancy of 21 either being in jail or dead?”

These items you mention have nothing to do with self-esteem.

Maybe, just maybe, is it possible that you have a distorted view of self-esteem? Or in the least, a distorted view of what builds healthy self-esteem?

I may be wrong on my position as well. But I have made a fifteen-year study of this on and off [as well as other accompanying issues], and I feel confident in saying I have a good grasp on the subject. Whereas most I meet haven’t heard about self-esteem as currently applied by educators as being harmful.

They merely defend the status quo or what they have accepted as the truth of the matter… without critically analyzing their own views on it. So I am use to — when presenting this to others — getting an immediate visceral response. When the person then goes and investigates the matter for themselves, usually their story changes over a year or two.

I want to give an example of two organizations, one that gives kids the proper tools to accomplish self-esteem for themselves and the other one who preaches defeat constantly. This can be exemplified in the dichotomy between what a commentator calls “victacrats,” like Rainbow/Push Coalition with the guiding hand of Rev. Jesse Jackson and that of BOND with the guiding hand of Rev. Jesse Lee Peterson. Two ways of dealing with one’s surroundings, one is optimistic (has hope and goals), one pessimistic (always trying to “keep hope alive,” because apparently it is always under attack).

Jordan Peterson – Self-esteem Doesn’t Exist

Here is an interaction with another gal, Jodi. I assume from the “quote marks” around “tolerant,” she was anything but.

Jodi,

I truly appreciate your boldness. It is refreshing, and “tolerant” (see my other post).

I want to post some quotes from another article, which I kindly ask any here to read, it is quite interesting. And tell me as you read this if this sounds like some of the more “hooligan” type kids on campus:

… But a spate of recent articles suggests that the tide may be turning. When Senator Robert Torricelli failed to admit wrongdoing as he resigned, Andrew Sullivan’s opinion piece in Time magazine (October 7, 2002) blamed “the sheer, blinding brightness of the man’s self-love” on the self-esteem movement. An article by Erica Goode in the New York Times (October 1, 2002) proclaimed that “‘D’ students . . . think as highly of themselves as valedictorians, and serial rapists are no more likely to ooze with insecurities than doctors or bank managers.” Worse, the writer said, some people with high self-esteem are likely to respond with aggression if anyone dares to criticize them: “Neo-Nazis, street toughs, school bullies . . . combine preening self-satisfaction with violence.”

In the pages of the New York Times Magazine (February 3, 2002), psychologist Lauren Slater maintained that the self-esteem movement has produced a “discourse of affirmation” that ladles out praise regardless of achievement. She concluded that self-appraisal and self-control need to take the place of self-esteem in psychotherapy. In the Christian Science Monitor (October 24, 2002), conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza said of self-esteem that “unlike honor, it does not have to be earned.”

Most such media critiques draw on the well-publicized research findings of the same three social psychologists: Roy Baumeister, Jennifer Crocker, and Nicholas Emler. But, as we shall see, these psychologists rely on mistaken conceptions of self-esteem and on flawed research methods.

PSYCHOLOGISTS AGAINST SELF-ESTEEM

Roy Baumeister, a professor of psychology at Case Western Reserve University, is the academic psychologist best known for claiming that “D” students, gang leaders, racists, murderers, and rapists have high self-esteem. Examining empirical studies on how murderers and rapists respond to self-defining statements, Baumeister and his colleagues have pointed out that these individuals consciously believe they are superior, not inferior—a belief that, Baumeister says, is characteristic of high self-esteem.

Baumeister does not claim that high self-esteem necessarily leads to aggression; in order to do so, it must be combined with an ego threat (a challenge to one’s high self-appraisal). In a study that has gotten less media attention, Baumeister and Brad Bushman tested this hypothesis experimentally. Participants were given the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, which contains such items as “If I ruled the world it would be a much nicer place,” and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. (See below for more about these questionnaires.) The ego threat was a strong criticism of the participant’s intellectual competence. Participants were given the opportunity to aggress against the people who had criticized them, by delivering a blast of noxious noise. (Since this was a social psychology experiment, the noise was not really delivered to the critic.) What the results showed was that the narcissism measure, not the self-esteem score, predicted the strength of the aggressive response (the intensity and duration of the noise). But because those who scored high on the narcissism questionnaire also tended to score high on the self-esteem scale, it looked as though some people with “high” self-esteem are aggressive when their sense of self is threatened.

The research of Jennifer Crocker, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, has indicated that deriving one’s self-esteem from certain “external” contingencies, such as appearance, is associated with potentially destructive behavior, including alcohol and drug use, and eating disorders. Crocker and her colleagues conducted a study with applicants to graduate programs who based their self-esteem on academic competence. They found that such students showed greater increases in self-esteem on days of acceptance and greater decreases on days of rejection. The stability of self-esteem is an important area of investigation because several studies have found that people whose self-esteem is unstable (that is, fluctuates substantially on a daily basis) are more emotionally reactive to everyday events. They are more likely to become depressed when confronted with daily hassles and are more prone to anger when their self-esteem is threatened.

Crocker’s findings have led her to conclude that the pursuit of self-esteem has significant costs. Crocker has gone on to contend that self-esteem ought to be non-contingent: not based on any source at all. If people value themselves positively without conditions or criteria, Crocker maintains, they will be less likely to suffer from problem drinking, maladaptive hostile reactions, and depression.

Nicholas Emler, a psychologist at the University of Surrey, is a researcher whose work has garnered extensive media attention in Great Britain. He also believes that high self-esteem is a source of trouble. His 2001 monograph Self-Esteem: The Costs and Causes of Low Self-Worthreviews a wide range of published research, concluding that low self-esteem is not a risk factor for delinquency, violence against others, or racial prejudice. On the contrary, he suggests, high self-esteem is the more plausible risk factor. Relying on Baumeister’s and Crocker’s evidence about the pitfalls of self-esteem, as well as other research, Emler asserts that people with high self-esteem are more likely to engage in risky pursuits, such as driving too fast and driving drunk. Lastly, Emler finds little evidence that self-esteem and educational attainment are associated, since even failing students can show high self-esteem on questionnaires. …

Does any of that ring true to you… just a bit? And the question then becomes Jodi, do you have a degree that gives you the tools to delineate between proper (i.e., earned) self-esteem and narcissism?

I don’t, and when I look into who writes the textbooks and teacher resources on this matter, they do not either. Instead, they merely accept the latest fad, like outcome-based education. When I deal with other people’s kids I do not bet their kids to pop-psychology. And I let their parents know that I don’t.

Thank you again for the thoughtful challenge.

I was trying to be as gracious as I could.

Parents want to do all they can to help their kids become happy, independent adults, but the question is, how do we do that? For the last 30 years, parents have heard that instilling “high self-esteem” is the secret to raising successful children. But the research does not support that. In fact, the quality of ‘high self-control’ is emerging as the most important trait. This talk by Heidi Landes, parent coach and mother of 4, looks at the research around these concepts, as well as giving parents simple ways to encourage their children to develop greater self-control, and a greater chance of success in adulthood.

Heidi Landes is a parent coach who started a coaching business called Courage for Parents with her husband, Gabe. Their mission is to help parents prepare their children for life. They also serve as a host family for medical mission children from Africa and travel with their family to Mexico several times a year to volunteer at an orphanage. Heidi received an undergraduate degree from Miami University and a MBA from the University of Dayton. Early in her career, she founded TeenWorks, Inc., a faith-based nonprofit that taught entrepreneurialism to youth, and served on the board of Her Star Scholars, an organization that sends young girls to school in underdeveloped countries. Heidi and her husband live in Dayton with their four children.

Dr. Paul Vitz notes the end result of what Dr. Baumeister confirms:

…Finally, the whole focus on ourselves feeds unrealistic self love. What psychologists often call narcissism. One would have thought America had enough trouble with narcissism in the 70s which was the Me Generation and in the 80s with the yuppies. Today, the search for self-esteem is just the newest expression of America’s old egomania.

In giving school children happy faces for all their homework just because it was handed in or giving them trophies for just being on the team is flattery of the kind found for decades in our commercial slogans “You deserve a break today,” “You are the boss,” “Have it your way.” Such self love is an extreme expression of an individualistic psychology long supported by our consumer world. Now, it is reinforced by educators who gratify the vanity of even our youngest children with repetitive mantras like “You are the most important person in the whole world.”

This narcissistic emphasis in American society and especially in education and to some extent in religion is a disguised form of self worship. If accepted, America would have 250 million “most important persons in the whole world.” Two hundred and fifty million golden selves. If such idolatry were not socially so dangerous, it would be embarrassing, even pathetic. Let’s hope common sense makes something of a come back…..

Here is more… a “for instance” via PSYCHOLOGY TODAY in an article notes the following:

As a culture, we are highly concerned with self-esteem. And this is a good thing. How we feel about ourselves determines how we treat those around us and vice versa. In 1890, William James identified self-esteem as a fundamental human need, no less essential for survival than emotions such as anger and fear. And yet, we often fail to measure the many distinctions between self-esteem and vanity, or we fail to understand how our actions and reactions can serve to bolster one as opposed to the other.

Terror management theorist Dr. Sheldon Solomon makes the point that self-esteem is “controversial as some claim that it is vitally important for psychological and interpersonal well-being, while others insist that self-esteem is unimportant or is associated with increased violence and social insensitivity.” He goes on to say that “those who claim that high self-esteem is problematic and associated with increased aggression are either willfully or unwittingly confusing and [equating] self-esteem with narcissism.”

The distinction between self-esteem and narcissism is of great significance on a personal and societal level. Self-esteem differs from narcissism in that it represents an attitude built on accomplishments we’ve mastered, values we’ve adhered to, and care we’ve shown toward others. Narcissism, conversely, is often based on a fear of failure or weakness, a focus on one’s self, an unhealthy drive to be seen as the best, and a deep-seated insecurity and underlying feeling of inadequacy. So where do these attitudes come from? And why do we form them?

[….]

Studies have shown that children offered compliments for skills they haven’t mastered or talents they do not possess are left feeling as if they’d received no praise at all, often even emptier and less secure. Only children praised for real accomplishments were able to build self-esteem. The others were left to develop something far less desirable–narcissism. Unnatural pressure or unearned buildup can lead to increased insecurities and anxieties that foster narcissism over self-confidence.

THE GUARDIAN expands on the emptiness of this modern educational push and the miapplication of it:

A widespread view among teachers and social workers that delinquency, violence and under-achievement can be blamed on people’s low self-esteem is debunked today in research commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Nicholas Emler, a social psychologist at the London School of Economics, claims to have exploded the myth that a limited sense of self-worth lies behind just about every personal and social ill – from drug abuse and racism to poverty and business failure.

“Widespread belief in ‘raising self-esteem’ as a cure for social problems has created a huge market for self-help manuals and educational programmes that threatens to become the psychotherapeutic equivalent of snake oil,” he says. “Unfortunately, many of the claims made about self-esteem are not rooted in hard evidence.”

Individuals with an unjustifiably high opinion of themselves often pose a greater threat to those around them than do people whose sense of self-worth is unusually low, Emler argues.

The research, Self-esteem: The Costs and Causes, is based on analysis of studies of children and young people, linking measurement of their self-esteem to their subsequent behaviour. Emler found relatively low self-esteem did not lead people into delinquency, violence (including child and partner abuse), drug use, alcohol abuse, educational under-attainment or racism.

On the other hand, young people with very high self-esteem were more likely than others to hold racist attitudes, reject social pressures from adults and peers and engage in physically risky pursuits, such as drink-driving or driving too fast.

The research identified a few areas where low self-esteem could be a risk factor. It made people more liable to suicide, depression, teenage pregnancy and victimisation by bullies. But in each case a low sense of self-worth was only one of several risk factors.

Emler found that parents had the most influence on young people’s level of self-esteem – both through genetic inheritance and upbringing. The effects of high or low achievement at school were relatively small.

All of this is of course rooted in Abraham Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs,” Carl Rogers’ Self-Image, or John Dewey’s “Whole Person. The progressive, humanistic endeavors give zero tools to the educator to distinguish between narcissism and a healthy value based and merit based self-esteem.

In this video I provide a short introduction to the ideas of humanistic psychologists Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. Maslow and Rogers both emphasized the role of an intrinsic drive towards self-actualization, or fulfilling one’s greatest potential, in shaping an individual.

What is Secular Humanism? Most teachers end up being engrained with this reductionistic religion, whether they realize it or not:

Secular Humanism is a well-articulated worldview. This is evident from the three Humanist Manifestos written in 1933 and revised in 1973 and again in 2000. According to their own pronouncements, Secular Humanists are atheists who believe that the scientific method is the primary way we can know about life and living, from understanding who we are as humans to questions of ethics, social issues, and politics.

However, apart from the specifics of what Secular Humanists believe, the pressing issue is this: is Secular Humanism a religion? This is important in light of current discussions surrounding the idea of “separation of church and state.” That’s because this phrase has been used by the courts and secular organizations (such as American’s United Against Church and State) in an attempt to eradicate all mention of God from the public square, including public debates over social issues, discussions in politics, and especially regarding what is taught in public/government schools.

To verify that a number of major tenets of Secular Humanism are taught in public schools, one only needs to compare Secular Humanist beliefs with what is actually being presented through public school textbooks. For example, any text on psychology includes what are considered the primary voices in that field: Abraham Maslow, Eric Fromm, Carl Rogers, and B. F. Skinner, to name a few. Yet, each of these men are atheists who have been selected as “Humanist of the Year” by a major Secular Humanist organization. So why are almost all the psychologists studied in school Secular Humanists? Why are no Christian psychologists included in the curriculum? Is this balanced treatment of the subject matter being taught?

Or when it comes to law, why are the Ten Commandments, historically known to be the foundation for English Common Law and American jurisprudence, judged to be inappropriate material to be hung on the school wall, in a courtroom, or as part of a public display on government property? The answer, of course, is an appeal to the “separation” principle.

But if this is how the courts are going to interpret the separation principle, we must insist that this ruling be applied equally to all religious faiths, not favoring some others. Therefore, for the sake of fairness under the law, if Secular Humanism is a religious faith, too, then teaching the tenets of this religious faith must also be eliminated from public school textbooks and classroom discussions. …..

And SUMMIT has more on sel-esteem worth reading:

Historically, the concept of self-esteem has no clear intellectual origins; no major theorist has made it a central concept. Many psychologists have emphasized the self, in various ways, but the usual focus has been on self-actualization, or fulfillment of one’s total potential. As a result, it is difficult to trace the source of this emphasis on self-esteem. Apparently, this widespread preoccupation is a distillation of the general concern with the self — found in many psychological theories. Self-esteem seems to be the common denominator pervading the writings of such varied theorists as Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow, “ego-strength” psychologists, and various recent moral educators. In any case, the concern with self-esteem hovers everywhere in America today. It is, however, most reliably found in the world of education — from professors of education to principals, teachers, school boards, and television programs concerned with preschool children.

Self worth, a feeling of respect and confidence in one’s being, has merit, as we shall see. But an ego-centered, “let me feel good” self-esteem can ignore our failures and need for God.

What is wrong with the concept of self-esteem? Lots — and it is fundamental in nature. There have been thousands of psychological studies on self-esteem. Often the term self-esteem is muddled in confusion as it becomes a label for such various aspects as self-image, self-acceptance, self worth, self-trust, or self-love. The bottom line is that no agreed-upon definition or agreed-upon measure of self-esteem exists, and whatever it is, no reliable evidence supports self-esteem scores meaning much at all anyway. There is no evidence that high self-esteem reliably causes anything — indeed lots of people with little of it have achieved a great deal in one dimension or another.

For instance, Gloria Steinem, who has written a number of books and been a major leader of the feminist movement, recently revealed in a book-long statement that she suffers from low self-esteem. And many people with high self-esteem are happy just being rich, beautiful, or socially connected. Some other people whose high self-esteem has been noted are inner-city drug dealers, who generally feel quite good about themselves: after all, they have succeeded in making a lot of money in a hostile and competitive environment.

A 1989 study of mathematical skills compared students in eight different countries. American students ranked lowest in mathematical competence and Korean students ranked highest. But the researchers also asked students to rate how good they were at mathematics. The Americans ranked highest in self-judged mathematical ability, while the Koreans ranked lowest. Mathematical self-esteem had an inverse relation to mathematical accomplishment! This is certainly an example of a “feel-good” psychology, keeping students from an accurate perception of reality. The self-esteem theory predicts that only those who feel good about themselves will do well — which is supposedly why all students need self-esteem — but in fact feeling good about yourself may simply make you over-confident, narcissistic, and unable to work hard.

I am not implying that high self-esteem is always negatively related to accomplishment. Rather, the research mentioned above shows that measures of self-esteem have no reliable relationship to behavior, either positive or negative. In part, this is simply because life is too complicated for so simple a notion to be of much use. But we should expect this failure in advance. We all know, and know of, people who are motivated by insecurities and self-doubts. These are often both the heroes and the villains of history. The prevalence of certain men of small stature in the history of fanatical military leadership is well-documented: Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Hitler, and Stalin were all small men determined to prove they were “big.” Many great athletes and others have had to overcome grave physical disabilities and a lack of self-esteem. Many superior achievements appear to have their origin in what psychologist Alfred Adler called “inferiority completes.”

The point is not that feeling bad about ourselves is good, but rather that only two things can truly change how we feel about ourselves: real accomplishment and developing “basic trust.” First, real accomplishment in the real world affects our attitudes. A child who learns to read, who can do mathematics, who can play the piano or baseball, will have a genuine sense of accomplishment and an appropriate sense of self-esteem. Schools that fail to teach reading, writing, and arithmetic corrupt the proper understanding of self-esteem. Educators who say, “Don’t grade them, don’t label them. You have to make them feel good about themselves,” cause the problems. It makes no sense for students to be full of self-esteem if they have learned nothing. Reality will soon puncture their illusions, and they will have to face two disturbing facts: that they are ignorant, and that the adults responsible for teaching them have lied to them. In the real world praise has to be the reward for something worthwhile: praise must be connected to reality.

There is an even more fundamental way in which most people come to genuine self-esteem — actually, to feelings of self-worth and what psychologists call “basic trust.” Such feelings come through receiving love; first of all, our mother’s love. But this foundational experience of love and self-confidence cannot be faked. When teachers attempt to create this deep and motivating emotion by pretending they “love” all their students and by praising them indiscriminately, they misunderstand the nature of this kind of love. Parental love simply cannot be manufactured by a teacher in a few minutes of interaction a day for each of thirty or more students. The child not only knows that such love is “fake,” but that real teachers are supposed to teach, and that this involves not just support but discipline, demands, and reprimands. Good teachers show their love by caring enough to use discipline. Thus, the best, most admired teachers in our high schools today often are the athletic coaches. They still teach, but they expect performance, and they rarely worry about self-esteem.

Similar problems arise for those who try to build their own flagging self-esteem by speaking lovingly to their “inner child” — or other insecure inner selves. Such attempts are doomed to failure for two reasons: first, if we are insecure about our self-worth, how can we believe our own praise? And second, like the child, we know the need for self-discipline and accomplishment.

Self-esteem should be understood as a response, not a cause. It is primarily an emotional response to what we and what others have done to us. Though it is a desirable feeling or internal state, like happiness it does not cause much. Also, like happiness, and like love, self-esteem is almost impossible to get by trying to get it. Try to get self-esteem and you will fail. But do good to others and accomplish something for yourself, and you will have all you need.

The subject is vital for Christians, partly because so many are so concerned about it and partly because the recovery of self-esteem has been touted as tantamount to a new reformation. We must note, however, that self-esteem is a deeply secular concept — not one with which Christians should be particularly involved. Nor need they be. Christians should have a tremendous sense of self-worth: God made us in His image, He loves us, He sent His Son to save each of us; our destiny is to be with Him forever. Each of us is of such value that the angels rejoice over every repentant sinner. But on the other hand, we have nothing on our own to be proud of, we were given life along with all our talents, and we are all poor sinners. There is certainly no theological reason to believe that the rich or the successful or the high in self-esteem are more favored by God and more likely to reach heaven, indeed there is far more evidence to the contrary: “Blessed are the meek.”

In addition, self-esteem is based on the very American notion that each of us is responsible for our own happiness. Thus, within a Christian framework, self-esteem has a subtle, pathological aspect: we may take the “pursuit of happiness” as a far more intense personal goal than the pursuit of holiness. Today self-esteem has become very important because it is thought to be essential to happiness: unless you love yourself, you will not be happy. But to assume that we must love ourselves, that God will not love us as much as we need to be loved, is a form of practical atheism. We say we believe in God, but we don’t trust Him. Instead, many Christians live by the very unbiblical “God loves those who love themselves.”

Another problem is that Christians have begun to excuse evil or destructive behavior on the grounds of “low self-esteem.” But self-esteem, whether high or low, does not determine our actions. We are accountable for them and we are responsible for trying to do good and avoid evil. Low self-esteem does not make someone an alcoholic, nor does it enable a person finally to admit his or her addiction and do something about it. Both of these decisions are up to each of us regardless of one’s level of self-esteem.

Finally, the whole focus on ourselves feeds unrealistic self-love, which psychologists often call “narcissism.” One would have thought America had enough trouble with narcissism in the seventies with the “Me Generation,” and in the eighties with the Yuppies. But today’s search for self-esteem is just the newest expression of America’s old egomania. And giving schoolchildren happy faces on all their homework just because it was handed in or giving them trophies for just being on the team is flattery of the kind found for decades in our commercial slogans: “You deserve a break today”; “You are the boss”; and “Have it your way.” Such self-love is an extreme expression of an individualistic psychology long supported by consumerism. Now it is reinforced by educators who gratify the vanity of even our youngest children with repetitive mantras like “You are the most important person in the whole world.”

This narcissistic emphasis in our society, and especially in education and religion, is a disguised form of self-worship. If accepted, America would have 250 million “most important persons in the whole world,” 250 million golden selves. If such idolatry were not socially so dangerous, it would be embarrassing, even pathetic.

168 LGBTQA2+ Awareness Days

I am starting a new movement! LOL

Keep January LGBTTQQFAIPBGD7@bRs?PLWb+2Z9A2 Free!

If you tabulate all the days celebrated… we have 168 days noted in our countries calendar for the LGBTQA2+ persons.

One Hundred And Sixty Eight!

As you prepare for Pride Month, we must also remember to celebrate:

Bisexual Health Awareness Month

International Transgender Day of Visibility

National LGBT Health Awareness Week

National Transgender HIV Testing Day

Non-Binary Parents Day

Lesbian Visibility Day

International… pic.twitter.com/xW9mw5KUYU— The Matt Walsh Show (@MattWalshShow) May 30, 2023

This is the list from GLAAD

FEBRUARY

- February 7: National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- Week after Valentine’s Day: Aromantic Spectrum Awareness Week

- February 28: HIV Is Not A Crime Awareness Day

MARCH

- March: Bisexual Health Awareness Month

- Week varies in March: National LGBT Health Awareness Week

- March 10: National Women & Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- March 20: National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- March 31: International Transgender Day of Visibility

APRIL

- April 6: International Asexuality Day

- April 10: National Youth HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- Third Friday of April: Day of Silence

- April 18: National Transgender HIV Testing Day

- April 18: Nonbinary Parents Day

- April 26: Lesbian Visibility Day

MAY

- First Sunday In May: International Family Equality Day

- May 17: International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia

- May 19: National Asian & Pacific Islander HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- May 22: Harvey Milk Day

- May 24: Pansexual and Panromantic Awareness and Visibility Day

JUNE

- June: LGBTQ Pride Month

- June 1: LGBTQ Families Day

- June 12: Pulse Remembrance Day

- June 15: Anniversary of U.S. Supreme Court Bostock decision expanding protections to LGBTQ employees Day

- June 26: Anniversary of U.S. Supreme Court legalizing marriage equality Day

- June 27: National HIV Testing Day

- June 28: Stonewall Day

- June 30: Queer Youth of Faith Day

JULY

- Week of July 14: Nonbinary Awareness Week, culminates in International Nonbinary People’s Day on July 14

- July 16: International Drag Day

AUGUST

- August 14: Gay Uncles Day

- August 20: Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

SEPTEMBER

- September 18: National HIV/AIDS & Aging Awareness Day

- Week of September 23: Bisexual+ Awareness Week, culminates in Celebrate Bisexuality Day on September 23

- September 27: National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

OCTOBER

- October: LGBTQ History Month

- October 8: International Lesbian Day

- October 11: National Coming Out Day

- October 15: National Latinx HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- October 19: National LGBT Center Awareness Day

- Third Wednesday in October: International Pronouns Day

- Third Thursday in October: Spirit Day

- Last week in October: Asexual Awareness Week

- October 26: Intersex Awareness Day

NOVEMBER

- First Sunday of November: Transgender Parent Day

- November 13 – 19: Transgender Awareness Week

- November 20: Transgender Day of Remembrance

DECEMBER

- December 1: World AIDS Day

- December 8: Pansexual/Panromantic Pride Day

- December 14: HIV Cure Research Day

The Law Is Clear, Life Begins In The Womb (Scott Peterson)

I saw the video [to the right] on Seth Gruber’s Rumble, and I realized I did not have a post here concerning Scott Peterson.

So I wish to fill in the gap with this posting. What follows are some pro-life apologists using Scott Peterson as an example to argue for the life, from conception. Who is Scott Peterson? — for my younger audience.

Who Is Scott Peterson?

In a case that riveted the nation, Scott Peterson was convicted of killing his eight-month pregnant wife, Laci, in 2002. With the help of his mistress, who had not previously known he was married, the FBI was able to collect evidence for the case against him. He was sentenced to death by lethal injection in 2004 for the first-degree murder of his wife and the second-degree murder of their fetus son.

In doing some searching for “stuff” for this post, I came across this blogpost by SECUALR PRO-LIFE… an atheist pro-lifer (yes, THEY EXIST, but they DO – NOT… lol). Here is a portion of that post that mentions Scott Peterson — and brought me to a video I likewise isolated, edited, and posted to my RUMBLE. Both the text and the video discuss what pro-life philosopher, Trent Horn, calls “Golden Retriever Reasoning.”

Enjoy:

Gradualism

This is the argument that pro-life philosopher Trent Horn referred to as Golden Retriever Reasoning. This position essentially states that the unborn don’t have the same value that we do, but they do have some value, just like dogs do. It would be wrong for me to kill my neighbor’s Golden Retriever, not because he’s as valuable as humans but because he belongs to my neighbor. Additionally, you shouldn’t just kill them for a trivial reason, but if circumstances get very tough, then you are justified in killing them.

But as Trent points out in the video, this doesn’t account for why we treat the unborn as no different than infants in some situations (for example, in some states if you kill a wanted unborn child you are charged with murder, not animal cruelty, such as when Scott Peterson killed his pregnant wife and unborn child in California several years ago; he was charged with two counts of murder). In fact, many pro-choice people do treat the unborn as babies if they’re wanted.

We don’t become “more human” by developing further, we just develop more of the traits that humans possess. Similarly, we don’t become “more of a person” by developing further, we just develop the capacity to perform the functions that persons can perform.

So the Gradualist position just doesn’t account for why abortion should be available, especially on demand as we currently have it in the United States now.

(I also add a clip from Seth Gruber)

Much more can be found at my Roe v. Wade post: SCOTUS Overturns Roe/Casey!

SEA TURTLES VS. HUMANS

Bill Maher: Kathy, why do you oppose a women’s right to choose

Kathy Ireland: Bill, when my husband was going to medical school I underwent a transformation. Because I used to be in favor of abortion. But I noticed when I was reading through some of his medical teaching books, that according to a law in science known as the law of biogenesis, every living thing reproduces after it own kind. That means dog produce dogs, cats produce cats, humans produce humans. If we want to know what something is we simply ask what are its parents. If we know what the parents are, we know what the thing in question is. And I reasoned from that because human parents can only produce human offspring, unborn human fetuses could be nothing but human beings, because the law of biogenesis rules out every other alternative. And I concluded therefore that because human fetuses were part of our family, we should not harm them without justification.

Mr. B responds to the claim that “life begins at conception” is only a religious belief.

This is an excerpt from Randy Alcorn’s book (older edition), “Pro-Life Answers to Pro-Choice Arguments Expanded & Updated“

It is uncertain when human life begins; that’s a religious question that cannot be answered by science.

An article printed and distributed by the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL [the original, and still largest pro-choice organization]) describes as anti-choice the position that human life begins at conception. It says the pro-choice position is, Personhood at conception is a religious belief, not a provable biological fact.

Bill O’Reilly of Fox News said on July 3, 2000, “No one knows when human life begins.” He made no distinction between biological life and any other kind of life. Mr. OReilly then went on to ask a guest if “is an embryo in a [petri] dish a human life”? Sen. Hatch’s claim that “an embryo in a petri dish is not a human life”?

1a. If there is uncertainty about when human life begins, the benefit of the doubt should go to preserving life.

[One of the reasons the Supreme Court allowed the legalization of abortion is that they werent sure of when life began.] Suppose there is uncertainty about when human life begins. If a hunter is uncertain whether a movement in the brush is caused by a person, does his uncertainty lead him to fire or not to fire? If youre driving at night and you think the dark figure ahead on the road may be a child, but it may be just a shadow of a tree, do you drive into it or do you put on the brakes? If we find someone who may be dead or alive, but were not sure, what is the best policy? To assume he is alive and try to save him, or to assume he is dead and walk away?

Shouldn’t we give the benefit of the doubt to life? Otherwise we are saying, This may or may not be a child, therefore it’s all right to destroy it.

1b. Medical Textbooks and scientific reference works constantly agree that human life begins at conception.

Many people have been told that there is no medical or scientific consensus as to when human life begins. This is simply untrue. Among those scientists who have no vested (monetary) in the abortion issue, there is an overwhelming consensus that human life begins at conception. (Conception is the moment when the egg is fertilized by the sperm, bringing into existence the zygote, which is a genetically distinct individual.)

Dr. Bradley M. Pattens textbook, Human Embryology, states:

- It is the penetration of the ovum by a spermatozoan and the resultant mingling of the nuclear material each brings to the union that constitutes the culmination of the process of fertilization and marks the initiation of a new individual.

Dr. Keith L. Moores text on embryology, referring to the single cell zygote, says:

- The cell results from fertilization of an oocyte by a sperm and is the beginning of a human being. He also states, Each of us started life as a cell called a zygote.

Doctors J. P. Greenhill and E. A. Friedman, in their work on biology and obstetrics, state:

- The zygote thus formed represents the beginning of a new life.

Dr. Louis Fridhandler, in the medical textbook Biology of Gestation, refers to fertilization as:

- that wondrous moment that marks the beginning of life for a new unique individual.

Doctors E. L. Potter and J. M. Craig write in Pathology of the Fetus and the Infant:

- Every time a sperm cell and ovum unite a new being is created which is alive and will continue to live unless its death is brought about by some specific condition.

Popular scientific reference works reflect this same understanding of when human life begins. Time and Rand McNallys Atlas of the Human Body states:

- In fusing together, the male and female gametes produce a fertilized single cell, the zygote, which is the start of a new individual.

In an article on pregnancy, the Encyclopedia Britannica says:

- A new individual is created when the elements of a potent sperm merge with those of a fertile ovum, or egg.

These sources confidently affirm, with no hint of uncertainty that life begins at conception. They state not a theory or hypothesis and certainly not a religious belief every one is a secular source. Their conclusion is squarely based on the scientific and medical facts.

1c. Some of the worlds most prominent scientist and physicians testified to a U. S. Senate committee that human life begins at conception.

In 1981, a United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee invited experts to testify on the question of when life begins. Al of the quotes from the following experts come directly from the official government record of their testimony.

Dr. Alfred M. Bongioanni, professor of pediatrics and obstetrics at the University of Pennsylvania, stated:

- I have learned from my earliest medical education that human life begins at the time of conception. I submit that human life is present throughout this entire sequence from conception to adulthood and that any interruption at any point throughout this time constitutes a termination of a human life.

I am no more prepared to say that these early stages [of development in the womb] represent an incomplete human being than I would be to say that the child prior to the dramatic effects of puberty is not a human being. This is human life at every stage.

Dr. Jerome LeJeune, professor of genetics at the University of Descartes in Paris, was the discoverer of the chromosome pattern of Downs syndrome. Dr. LeJeune testified to the Judiciary Subcommittee that:

- after fertilization has taken place a new human being has come into being. He stated that this is no longer a matter of taste or opinion, and not a metaphysical contention, it is plain experimental evidence. He added, Each individual has a very neat beginning, at conception.

Professor Hymie Gordon, Mayo Clinic:

- By all the criteria of modern molecular biology, life is present from the moment of conception.

Professor Micheline Matthews-Roth, Harvard University Medical School:

- It is incorrect to say that biological data cannot be decisive. It is scientifically correct to say that an individual human life begins at conception. Our laws, one function of which is to help preserve the lives of our people, should be based on accurate scientific data.

Dr. Watson A. Bowes, University of Colorado Medical School:

- The beginning of a single human life is from a biological point of view as simple and straightforward matter the beginning is conception. This straightforward biological fact should not be distorted to serve sociological [familial, age, or medical advances], political [pro-choice], or economic goals [cannot finish school].

A prominent physician points out that at these Senate hearings, Pro-abortionists, though invited to do so, failed to produce even a single expert witness who could specifically testify that life begins at any other point other than conception or implantation.

1d. Many other prominent scientists and physicians have likewise affirmed with certainty that human life begins at conception.

Ashley Montague, a geneticist and professor at Harvard and Rutgers, is unsympathetic to the pro-life cause. Nevertheless, he affirms unequivocally, The basic fact is simple: Life begins not at birth, but conception.

Dr. Bernard Nathanson, internationally known obstetrician and gynecologist, was co-founder of what is now the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL [Dr. Nathanson help start the entire pro-choice movement]). He owned and operated what was at the time the largest abortion clinic in the Western hemisphere. He was directly involved in over sixty thousand abortions.

Dr. Nathansons study of developments in the science of fetology and his use of ultrasound to observe the unborn child in the womb led him to the conclusion that he had made a horrible mistake. Resigning from his lucrative position, Nathanson wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine that he was deeply troubled by his increasing certainty that I had in fact presided over 60, 000 deaths.

In his film, The Silent Scream, Dr. Nathanson later stated, Modern technologies have convinced us that beyond question the unborn child is simply another human being, another member of the human community, indistinguishable in every way from us. Dr. Nathanson wrote Aborting America to inform the public of the realities behind the abortion rights movement of which he had been a primary leader. At the time Dr. Nathanson was an atheist. His conclusions were not even remotely religious, but squarely based on the biological facts.

Dr. Lundrum Shettles was for twenty-seven years attending obstetrician-gynecologist at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York. Shettles was a pioneer in sperm biology, fertility, and sterility. He is internationally famous for being the discoverer of male- and female- producing sperm. His intrauterine photographs of preborn children appear in over fifty medical textbooks. Dr. Shettles staes:

- I oppose abortion, I do so, first, because I accept what is biologically manifest that human life commences at the same time of conception and, secondly, because I believe it is wrong to take innocent human life under any circumstances. My position is scientific, pragmatic, and humanitarian.

The official Senate report on Senate Bill 158, the Human Life Bill, summarized the issue this way:

- Physicians, biologists, and other scientists agree that conception marks the beginning of the life of a humans being a being that is and is a member of the human species. There is overwhelming agreement on this point in countless medical, biological, and scientific writings.

Does It Matter?

In a statement form the The Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity, Director of Media and Policy Daniel McConchie said:

- “Stem cell lines are quickly becoming marketable items. Once some integral human parts can be bought and sold, we run the risk that democratic societies will decide that other weak and defenseless members of the human race in those societies can be utilized for profits as well.”

Jews and Blacks were once said by the courts to be less than human, I wonder if we are headed down that path again?

Democrats Don’t Actually Want To Debate Abortion (Matt Walsh)

Glamour Magazine Has Earth Shattering/Breaking News! (Matt Walsh)

Yes, it is the biggest story of the millennia… except it isn’t. Matt Walsh explains:

The TV “green screen” is via GLOBAL KREATORS excellent YouTube Channel

More via THE DAILY WIRE: (As an aside, the picture I include technically is a naked woman, mutilated and deluded. But nonetheless, a woman. Not even a transgender, but a transvestite — getting the terminology “straight” [pun intended].)

Glamour U.K. kicked off “Pride” month by featuring a pregnant female who identifies as a transgender male on the cover, writing in the featured piece that “he gave birth,” language many slammed on social media.

The fashion magazine features author Logan Brown on the cover — topless and covered in paint designed to look like a partial three-piece suit. The headline reads, “Trans Pregnant Proud.”

In several posts on Instagram, the magazine included clips from the Brown interview, with the outlet writing that they had met Brown “two weeks before he gave birth to his daughter, Nova, to talk about queer love, gender dysphoria, and navigating the NHS as a pregnant transgender man.”

“I spent so much time feeling shame and being hard on myself until I thought, ‘You can enjoy this process or make it really difficult for yourself,’” Brown said in the piece. “I’m a pregnant man, and I’m proud to do what I’m doing…”

Brown, whose partner is a non-binary drag queen performer in the U.K., also told the outlet, “I took a pregnancy test, and it was positive. I’d been off testosterone for a while due to some health issues. It was like my whole world just stopped. That everything, all my manlihood that I’ve worked hard for, for so long, just completely felt like it was erased.”

[….]

Libs Of TikTok shared the cover on Twitter, with many people reacting to the headlines and comments Brown made in the article, blasting them as a “lie” and more.

“As a student of biology, that isn’t how that works,” one person wrote.

“He was able to give birth only because he’s not a ‘he,’” another tweeted. “Corrupting the language won’t make fantasies become reality. Demanding that all of Society upends itself to please a tiny group of severely troubled people is unreasonable & it’s not helpful to those in desperate need.”

“He did not give birth, she did,” one person wrote. “XY DNA is male; XX is female. There are two sexes.”

While another tweeted, “This is so unnatural. There is nothing cute about this at all. Men don’t get pregnant and give birth. They can’t even produce milk.”……

Truth Doesn’t Always Find Friends (Galatians 4:16)

Watching Matt Walsh yesterday he said something that made me wanna excerpt it. I didn’t get to it last night, and luckily I didn’t. This morning at a men’s group discussion during small groups a verse on truth came up (Galatians 4:16), and that reminded me of a J. Vernon McGee commentary, which brought me to Chuck Smith as well (also discussed at the meeting this morning). Of course this short video wouldn’t be complete without Jack Nicholson’s character in the movie “A Few Good Men,” Colonel Nathan R. Jessep, talking about truth. So I hope this hits the right nerve with some who happen upon this.

Here are some commentaries on Galatians 4:16

Have I now become your enemy by telling you the truth? (HCSB)

Truth is not always relished where sin is nourished

L. Moody, Notes from My Bible: From Genesis to Revelation (Chicago; New York; Toronto: Fleming H. Revell, 1895), 165.

A person with pure motives and real friendship does not always say things that are pleasant to hear. Paul was telling the Galatians the truth, and as result was being labeled as their enemy. Sometimes the truth hurts; but a faithful friend would courageously confront another.

Earl D. Radmacher, Ronald Barclay Allen, and H. Wayne House, The Nelson Study Bible: New King James Version (Nashville: T. Nelson Publishers, 1997), Ga 4:16.

I had always wanted to place on the pulpit, facing the preacher, the words, “Sir, we would see Jesus.” A very fine officer of the church I served in downtown Los Angeles did this for me after he heard me express this desire. There is another verse I wanted to place on the audience side of the pulpit, but I never had the nerve to do it. It is these words of Paul: “Am I therefore become your enemy, because I tell you the truth?” As you know, many folk today really don’t want the preacher to tell the truth from the pulpit. They would much rather he would say something complimentary that would smooth their feathers and make them feel good. We all like to have our backs rubbed, and there is a lot of back-rubbing from the contemporary pulpit rather than the declaration of the truth.

Vernon McGee, Thru the Bible Commentary, electronic ed., vol. 5 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997), 179.

QUESTION—Is this a question or a statement?

- It is a rhetorical question [BNTC, Lns, Lt, Mor, NIGTC, NTC; all versions]: because I am being truthful to you, have I therefore become your enemy? The Galatians do not appear to be able to tolerate the truth [NTC]. Paul wants them to face the reality of what they were doing. Paul was not their enemy when he initially preached the gospel to them, and as he continued to do so, and they should see it as a friendly gesture, not as a hostile one [Mor]. Paul wanted them to realize that he was truly their friend even though he had to use strong language in this letter and possibly in the previous letter [NTC].

- It is a statement [ICC, NCBC, NIBC, NIC, SSA, WBC]: therefore it appears that I have become your enemy because I am being truthful to you! The idea is ‘So I have become your enemy!’ and this reflects the Judaizers’ view of Paul, not Paul’s [NCBC]. The conjunction ὥστε ‘therefore’ indicates a conclusion from the facts stated in 4:14–15: Since they once regarded Paul with such great affection and now consider him as an enemy, this could only come about because he had been telling them the truth [ICC, WBC].

Robert Stutzman, An Exegetical Summary of Galatians, 2nd ed. (Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2008), 160.

become your enemy There come times with all God’s servants when certain people proclaim something fresh and new in doctrine, and then the old messenger of God, who was blessed to them, comes to be despised. I have lived long enough to see dozens of very fine fancies started, but they have all come to nothing. I daresay I shall see a dozen more, and they will all come to nothing. But here I stand. I am not led astray either by novelties of excitement or novelties of doctrine. The things which I preached at the first, I preach still, and so I shall continue, as God shall help me. But I know, in some little measure, what the apostle meant when he said, “Am I therefore become your enemy, because I tell you the truth?”

by being truthful to you There are many who have incurred enmity through speaking the gospel very plainly, for the natural tendency of man is toward ceremony, toward some form of legal righteousness: he must have something aesthetic, something that delights his sensuous nature, something that he can see and hear, to mix up that with the simplicity of faith. Paul was as clear as noonday against everything of that kind, and so the Galatians got at last to be angry with him. Well, he could not help that, but it did grieve him.

Charles Spurgeon, Galatians, ed. Elliot Ritzema, Spurgeon Commentary Series (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2013), Ga 4:16.

Am I therefore become your enemy? He now returns to speak about himself. It was entirely their own fault, he says, that they had changed their minds. Though it is a common remark, that truth begets hatred, yet, except through the malice and wickedness of those who cannot endure to hear it, truth is never hateful. While he vindicates himself from any blame in the unhappy difference between them, he indirectly censures their ingratitude. Yet still his advice is friendly, not to reject, on rash or light grounds, the apostleship of one whom they had formerly considered to be worthy of their warmest love. What can be more unbecoming than that the hatred of truth should change enemies into friends? His aim then is, not so much to upbraid, as to move them to repentance.

John Calvin and William Pringle, Commentaries on the Epistles of Paul to the Galatians and Ephesians (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 129–130.

Paul’s emotion betrays itself in the ellipsis of his thought. At one time the Galatians counted themselves blessed for having Paul in their midst, but this is passed. Is the opposite now the case? And so have I become your enemy by telling you the truth?

Read this as a question; ὥστε means, “and so,” R. 999. “An enemy of yours” is active, one who hates you, and not passive, one who is hated by you (C.-K. 459). The perfect tense “have I become” is used in the Greek fashion from the standpoint of the readers and refers to the time when they read this letter in which Paul tells them the truth. Will they then say: “Paul has become hostile to us”? Ah, but it is the best and the truest friend who honestly tells us the truth about ourselves even when he knows we shall not like it. False friends are the ones who hide such truth from us and do so in order to remain in our favor.

Some regard this statement as a declaration: “Wherefore I have become your enemy by telling you the truth.” But that is not true (v. 19). If he intends to imply that the Galatians now consider him as being hostile to them, this thought is expressed far better by a question. The declarative idea is made more confusing when the inferior reading in v. 15 is adopted: τίς οὖν ἦν; “What, then, was your felicitation of yourselves?” and supplying in thought: “Nothing but superficiality,” and then attaching: “Wherefore I have become your enemy.” Paul regards the self-felicitation of the Galatians as being genuine; he even states the strongest reason for his so doing: that they were willing to sacrifice their eyes for him.

Again, Paul is not their enemy. Finally, the ὥστε clause cannot be construed across the intervening γάρ statement and attached to the question asked in v. 15. The reason: “I testify,” etc., would be contradicted by any declaration that Paul is an enemy of the Galatians. Regard the sentence as a question, and all is readily understood.

C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Paul’s Epistles to the Galatians, to the Ephesians and to the Philippians (Columbus, O.:Lutheran Book Concern, 1937), 222–223.

It was natural that a certain uneasy reserve should begin to mark the Galatian Christians’ attitude to Paul. They knew that the teaching to which they were now giving ear could not commend itself to him, and that he would disapprove of their accepting it. This reserve would be reinforced if they entertained suggestions tending to discredit him, or to diminish his standing in their eyes. When he heard of what was happening, he could be trusted to tell them they were wrong, and such plain speaking was bound to be unpalatable.

ὥστε is used here to introduce a rhetorical question.

It is hazardous to find in Paul’s use of ἐχθρὸς here the source of his later designation among the Ebionites as ἐχθρὸς ἄνθρωπος (Epistle of Peter to James, 2; Clem. Recog. 1.70f.), as is done by H.-J. Schoeps, Judenchristentum, 120, 474; Paul, 82; a much more probable source is the ἐχθρὸς ἄνθρωπος of Mt. 13:28 (cf. Schoeps, Judenchristentum, 127).

ἀληθεύων. In telling them the truth Paul is their best friend. The truth he is now telling them is the same as what he told them when first he came among them, and on that occasion it won their friendship for him. For this ‘truth’ is nothing other than the good news of divine grace. If it is true, then the ‘other gospel’ brought by the trouble-makers is self-evidently false. It is reading an alien idea into the text to say with W. Schmithals, ‘Precisely this argument of Paul shows that in truth people in Galatia were declaiming against Paul on account of the apostle’s fleshly [“sarkic”] weakness’ (Paul and the Gnostics, 50 n. 107).

The situation, in fact, is not unlike that in which Paul was later involved with the Corinthian church, when it was visited by interlopers who brought a ‘different gospel’ and tried to disparage Paul in his converts’ eyes; Paul protests his unchanging love for his friends, even while he remonstrates vigorously with them: ‘If I love you the more, am I to be loved the less?’ (2 Cor. 12:15).

F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1982), 211.

ὤστε ἐχθρὸς ὑμῶν γέγονα ἀληθεύων ὑμῖν, “so, [it seems,] I have become your enemy because I am telling you the truth!” Elsewhere in the NT ὤστε (“therefore,” “so”) is always used at the beginning of independent clauses to draw an inference from what has just been stated (cf. Gal 3:9, 24; 4:7, etc.). Most commentators acknowledge this. Yet almost all critical texts, translations and commentaries treat v 16 as a rhetorical question (e.g., WH, Souter, Nestle, UBSGT, KJV, RSV, JB, NIV, Lightfoot, Lietzmann, Oepke, Schlier, Mussner, Betz, Bruce), despite demurrings to the contrary (cf. Betz, Galatians, 228: “The connection of ὤστε [“therefore”] is certainly loose”; ibid., 228 n. 97: “ὤστε [“therefore”] introducing a question is odd”). Nonetheless, linguistically speaking, Burton, Zahn, and Sieffert are right: v 16 must be read as an indignant exclamation that draws an inference from what is stated in vv 14–15; “the appropriate punctuation is, therefore, an exclamation point” (Burton, Galatians, 244–45). It is not, of course, Paul’s own statement of relationships, but his evaluation of what seems to be his converts’ attitude: “So, [it seems,] I have become your enemy because I am telling you the truth!”

ἐχθρός, “enemy,” was the epithet given Paul by the later Ebionites (cf. Ps.-Clem. Hom., Ep. Pet. 2.3; Ps.-Clem. Recog. 1.70), though whether the Judaizers of Galatia ever used it of him is impossible to say. The modal present participial phrase ἀληθεύων ὑμῖν, “by telling you the truth,” refers not to some past proclamation, but to the truth Paul is now telling the Galatians, which, of course, is what he told them when he was first with them and which then won such a favorable response from them.

Richard N. Longenecker, Galatians, vol. 41, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1990), 193.

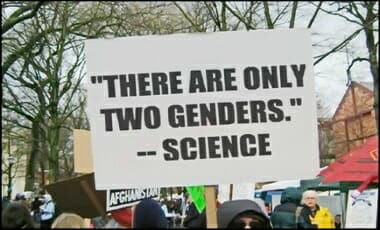

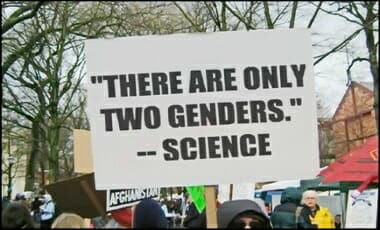

Princeton Professor’s Failure At Proving Gender Is a Spectrum

MATT WALSH dissects an article written by a Princeton professor who claims that he can prove that there are more than two sexes. The Ivy League professor, Agustín Fuentes, has specialized knowledge in “racism,” “sex/gender” and “chasing monkeys,” according to his biography page. He argued in Scientific American magazine on Monday that biological reproductive cells (gametes) – such as sperm and egg cells – does not delineate whether someone is male or female. (BREITBART)

A Transvestite EMT Debates Matt Walsh on “Genders”

When my fellow compatriots say “liberalism is a mental disorder,” it’s hard to disagree.

Dylan Mulvaney Celebrates “Womanhood” Even Though Still a Man

(ADDED CANDACE OWENS AT THE BOTTOM)

Today on the Matt Walsh Show, infamous male TikToker Dylan Mulvaney has a star-studded extravaganza in New York celebrating his “day 365 of girlhood.” The entire Daily Wire lineup made an appearance during the show. We’ll play the clip and talk about it. Joe Biden lashes out at those who want to protect children from abuse, calling us “sinful.” The president also uses an alleged letter from a child to promote the gender wage gap myth. Netflix quietly cancels its kid’s show featuring a non-binary bison. And in our Daily Cancellation, a conservative author is ruthlessly mocked by the Left for not being able to define the word “woke.” But since when is the Left in any position to make fun of anyone else for not being able to define a word?

PJ-MEDIA has this find:

…..I still haven’t quite recovered from the clip of Drew Barrymore kneeling before Dylan Mulvaney like he’s some sort of god, yet now I have to react to yet another clip featuring Mulvaney that is going viral — though, and this one is a real doozy, too.

This new footage features Mulvaney during an appearance on The Price is Right. And it.. well… just watch it.

Pre-Girlhood Dylan is the same as Dylan 365. pic.twitter.com/1c4JWyqOgy

— Dr. Jebra Faushay (@JebraFaushay) March 16, 2023

Upon watching this video, it becomes abundantly clear that Dylan Mulvaney is an individual who has always sought attention in a rather desperate manner. His flamboyant and over-the-top demeanor, coupled with a disposition reminiscent of the iconic Richard Simmons from Sweatin’ to the Oldies, is embarrassing and apparent.

It is true that contestants on The Price is Right are known to get very excited and even extremely animated, but have you ever seen a contestant engage in the kind of behavior exhibited by Mr. Mulvaney here? Upon winning the game he proceeds to flail around on the floor, prance about on stage, dance, and even fall down, and get back up in dramatic fashion. He literally performs for the cameras for close to a full minute.

According to a study published in the National Library of Medicine, patients with gender identity disorder (gender dysphoria) have a disproportionately high frequency of personality disorders. “The frequency of personality disorders was 81.4%. The most frequent personality disorder was narcissistic personality disorder (57.1%) and the least was borderline personality disorder. The average number of diagnoses was 3.00 per patient.”….

BEN SHAPIORO

Dylan Mulvaney has a video from when he was on The Price Is Right a few years ago. If you look closely, it appears he is putting on the same act today as he was then. So, this all an act?

The most absurd sight of the day is courtesy of Dylan Mulvaney. Yesterday, Dylan celebrated “365 Days of Girlhood” by dressing like a girl and putting on a musical at the Rainbow Room in New York. Dylan even gave the Daily Wire crew a shoutout at the end.

CANDACE OWENS

Candace Owens discusses Dylan Mulvaney’s celebration of “day 365 of ‘girlhood'” with a strange variety show that included me and the other Daily Wire hosts. What an honor. (Full Candace Owens episode HERE)