(Originally Posted June 2016)

The Dilemma [Challenge] Stated Clearly:

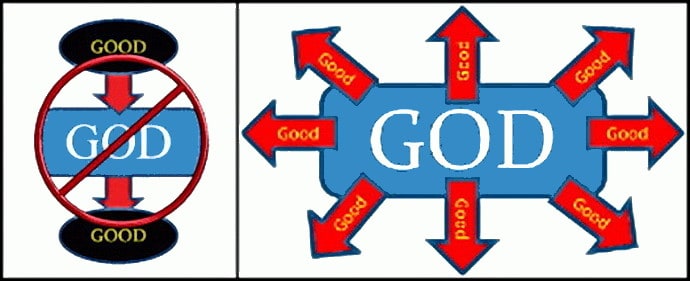

“Either something is good (holy) because God commands it or else God commands something because it is good.”

- If you say something is good because God commands it, this makes right and wrong arbitrary; In other words, God could have commanded that acts of hatred, brutality, cruelty, and so on be good. Making God Himself arbitrary and the commands His followers follow arbitrary as well.

- If God commands something because it is good, then good is independent of God. Thus, morality can’t claim to be based on God’s commands (and God Himself is bound by something “outside” Himself — nullifying the theists claim of omnipotence and omniscience.

(Here is a good less-than-five-minute telling of the above by a skeptic.)

One of the best short article’s comes from…

FREE THINKING MINISTRIES

…At first it seems like we’re stuck. Except, as mentioned earlier, this dilemma has been resolved for centuries: God is good. He is the source of goodness. He is the moral standard. His commands are not arbitrary, nor do they come from some standard external to him. They are good because they flow from his innate goodness. Dilemma averted.

Euthyphro is dead.

Now I know this doesn’t settle the issue of God’s goodness. Since this article is only intended to discuss the Euthyphro dilemma, I’ll just briefly touch on two related objections:

1 – God is not good. This is typically in response to an action or command from God in the Old Testament. And I agree that there are some things that are hard to understand and need to be discussed. But generally speaking, if we question God’s goodness, what are we judging him against? Our own moral standard? Then it’s our opinion against God’s and, if he truly exists, I’m going to trust his judgment over any finite, fallible human’s.

2 – How do we know that God is good? This question completely misses the point of Euthyphro’s resolution: God is the standard of goodness. There is nothing to compare him against or judge him by. But let’s suppose there does exist some higher moral standard. By applying this objection’s logic, we should ask “How do we know that this standard is good?” See the problem? You’re forever asking “How do we know?” to any moral standard. But if there is an objective moral standard, that is the standard by which morality is measured. It simply is good.

The best you can do is try to find some kind of inconsistency in God’s moral character. But then you can still only judge him against himself, which would point you back to objection 1. And even if you feel that one (or both) of these objections has not been resolved, my broader point is that the Euthyphro dilemma fails as a dilemma since there’s a third possible option, whether you like it or not. Thus, it’s an invalid argument.

Euthyphro is dead.

Why do skeptics keep digging him up? You may as well as ask why zombies keeps coming back. Because they do. That’s what makes them zombies. Bad arguments will always come back into fashion. But you need to see Euthyphro for what he is: a dead, defeated argument. Yet unlike zombies from TV shows and movies, he has no bite. He doesn’t even have teeth. His dilemma has been resolved for centuries….

C.A.R.M.

For those looking for a quick answer to the issue, here is a short video and explanation from the theistic worldview via CARM (and CARM’S YOUTUBE):

Here is more from CARM’S WEBSITE:

[What is it?]

The Euthyphro dilemma comes from Plato’s Euthyphro dialogue, which has had different forms over the centuries. Basically, it is “Are moral acts willed by God because they are good, or are they good because they are willed by God?” Another way of saying it is, does God say that things are moral because they are by nature moral, or do they become moral because God declares them to be?

The dilemma is that if the acts are morally good because they are good by nature, then they are independent of God and morality somehow exists apart from God. These acts would already be good in themselves, and God would have to appeal to them to “find out” what is good. Of course, This raises questions on how moral absolutes can exist as independent abstract entities apart from a divine being. On the other hand, if something is good because God commands that it is good, then goodness is arbitrary, and God could have called murder, good, and honesty not good. The problem here is that it means God could also be a tyrant if he so chose to be. But, he chooses to be nice.

Responding to the Euthyphro Dilemma

The Euthyphro dilemma is actually a false dichotomy. That is, it proposes only two options when another is possible. The third option is that good is based on God’s nature. God appeals to nothing other than his own character for the standard of what is good and then reveals what is good to us. It is wrong to lie because God cannot lie (Titus 1:2), not because God had to discover lying was wrong or that he arbitrarily declared it to be wrong. This means that God does not declare something to be good (ignoring his own nature) or say that something is good by nature (recognizing a standard outside of himself). Both of these situations ignore the biblical option that good is a revelation of God’s nature. In other words, God is the standard of what is good. He is good by nature, and he reveals his nature to us. Therefore, for the Christian, there is no dilemma since neither position in Euthyphro’s dilemma represents Christian theology.

TITUS 1:5

- in hope of eternal life, which God, who never lies, promised before the ages began [Greek: before times eternal] (ESV)

- in the hope of eternal life that God, who cannot lie, promised before time began. (HCSB)

- This faith and knowledge make us sure that we have eternal life. God promised that life to us before time began—and God does not lie. (ERV)

- My aim is to raise hopes by pointing the way to life without end. This is the life God promised long ago—and he doesn’t break promises! (MSG)

(Apologetic Press’s Graphic – link in pic)

WILLIAM LANE CRAIG

Another short dealing with this comes from ONE-MINUTE APOLOGIST’S YouTube interview with William Lane Craig:

(Here is Dr. Craig in a class setting teaching the issue [longer].)

FRANK TUREK

Here, Frank Turek and Hank Hanegraaff discuss the issue in under 4-minutes:

Hank is holding Frank’s Book at a certain page[s]… I will reproduce the sections prior to, as well as the section from his book on the Euthyphro Argument in the APPENDIX.

STAND TO REASON

There are “two horns” to the dilemma presented, but much like Plato does, we will split the horns with a third option and show that the two choices are false because there is a third viable option (the site where I grabbed this originally is gone, therefore, so is the link. STAND TO REASON has a good post that stands in as a supplemental link):

SPLITTING EUTHYPHRO’S HORNS

If a dilemma with limited choices is presented, you should always consider that these choices may not be your only options. Euthyphro’s case is a prime example. There is a third alternative… and who knows?, there could be others that no one has come up with yet, but Christianity teaches this third alternative for the basis of morality:

God wills something because He is good.

What does this mean? It means that the nature of God is the standard of goodness. God’s nature is just the way God is. He doesn’t ‘will’ Himself to be good, and kind, and just, and holy… He just is these things. His commandments to us are an expression of that nature, so our moral duties stem from the commands of a God who IS good… and loving… and just… not a God who arbitrarily decides that he will command something on a whim, but gives commandments that stem from His unchanging character.

If God’s character defines what is good. His commands must reflect His moral nature.

[….]

The Euthyphro dilemma is a false one because there is at least one other choice that splits the horns of the dilemma. This option, taught as part of the Christian doctrine of who God is, is perfectly consistent with the concept that God must exist for objective morality to exist in our world.

Plato came up with his own third option… that moral values simply exist on their own. No need for God. Later Christian thinkers equated this to God’s moral nature, like we just discussed. However, some argue that God is not necessary; that goodness and justice, etc. can exist on their own… this idea is often referred to as Atheistic Moral Platonism…. [see STAND TO REASON about “atheistic moral Platonism”]

PETER KREEFT

This is VERY simple to grasp, but here are more dealings with it, Peter Kreeft’s short DEALING WITH THIS supposed dilemma (his entire 20-topics is free online):

There are four possible relations between religion and morality, God and goodness.

Religion and morality may be thought to be independent. Kierkegaard’s sharp contrast between “the ethical” and “the religious,” especially in Fear and Trembling, may lead to such a supposition. But (a) an amoral God, indifferent to morality, would not be a wholly good God, for one of the primary meanings of “good” involves the “moral”—just, loving, wise, righteous, holy, kind. And (b) such a morality, not having any connection with God, the Absolute Being, would not have absolute reality behind it.

God may be thought of as the inventor of morality, as he is the inventor of birds. The moral law is often thought of as simply a product of God’s choice. This is the Divine Command Theory: a thing is good only because God commands it and evil because he forbids it. If that is all, however, we have a serious problem: God and his morality are arbitrary and based on mere power. If God commanded us to kill innocent people, that would become good, since good here means “whatever God commands.” The Divine Command Theory reduces morality to power. Socrates refuted the Divine Command Theory pretty conclusively in Plato’s Euthyphro. He asked Euthyphro, “Is a thing pious because the gods will it, or do the gods will it because it is pious?” He refuted the first alternative, and thought he was left with the second as the only alternative.

But the idea that God commands a thing because it is good is also unacceptable, because it makes God conform to a law higher than himself, a law that overarches God and humanity alike. The God of the Bible is no more separated from moral goodness by being under it than he is by being over it. He no more obeys a higher law that binds him, than he creates the law as an artifact that could change and could well have been different, like a planet.

The only rationally acceptable answer to the question of the relation between God and morality is the biblical one: morality is based on God’s eternal nature. That is why morality is essentially unchangeable. “I am the Lord your God; sanctify yourselves therefore, and be holy, for I am holy” (Lev. 11:44). Our obligation to be just, kind, honest, loving and righteous “goes all the way up” to ultimate reality, to the eternal nature of God, to what God is. That is why morality has absolute and unchangeable binding force on our conscience.

The only other possible sources of moral obligation are:

a. My ideals, purposes, aspirations, and desires, something created by my mind or will, like the rules of baseball. This utterly fails to account for why it is always wrong to disobey or change the rules.

b. My moral will itself. Some read Kant this way: I impose morality on myself. But how can the one bound and the one who binds be the same? If the locksmith locks himself in a room, he is not really locked in, for he can also unlock himself.

c. Another human being may be thought to be the one who imposes morality on me—my parents, for example. But this fails to account for its binding character. If your father commands you to deal drugs, your moral obligation is to disobey him. No human being can have absolute authority over another.

d. “Society” is a popular answer to the question of the origin of morality “this or that specific person” is a very unpopular answer. Yet the two are the same. “Society” only means more individuals. What right do they have to legislate morality to me? Quantity cannot yield quality; adding numbers cannot change the rules of a relative game to the rightful absolute demands of conscience.

e. The universe, evolution, natural selection and survival all fare even worse as explanations for morality. You cannot get more out of less. The principle of causality is violated here. How could the primordial slime pools gurgle up the Sermon on the Mount?

Atheists often claim that Christians make a category mistake in using God to explain nature; they say it is like the Greeks using Zeus to explain lightning. In fact, lightning should be explained on its own level, as a material, natural, scientific phenomenon. The same with morality. Why bring in God?

Because morality is more like Zeus than like lightning. Morality exists only on the level of persons, spirits, souls, minds, wills—not mere molecules. You can make correlations between moral obligations and persons (e.g., persons should love other persons), but you cannot make any correlations between morality and molecules. No one has even tried to explain the difference between good and evil in terms, for example, of the difference between heavy and light atoms.

So it is really the atheist who makes the same category mistake as the ancient pagan who explained lightning by the will of Zeus. The atheist uses a merely material thing to explain a spiritual thing. That is a far sillier version of the category mistake than the one the ancients made; for it is possible that the greater (Zeus, spirit) caused the lesser (lightning) and explains it; but it is not possible that the lesser (molecules) adequately caused and explains the greater (morality). A good will might create molecules, but how could molecules create a good will? How can electricity obligate me? Only a good will can demand a good will; only Love can demand love.

(TWENTY ARGUMENTS FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD: THE MORAL ARGUMENT)

MISC.

While Plato was dealing with polytheism and a form of monism, this argument as dealt with herein is response to the challenges presented to theism. However, his use of a third option is what we present here as well… making this dilemma mute. What was Plato’s solution?

- “You split the horns” of the dilemma by formulating a third alternative, namely, God is the good. The good is the moral nature of God Himself. That is to say, God is necessarily holy, loving, kind, just, and so on. These attributes of God comprise the good. God’s moral character expresses itself toward us in the form of certain commandments, which became for us our moral duties. Hence, God’s commandments are not arbitrary but necessarily flow from His own nature. (BE THINKING quoting Dr. Craig)

They [“the Good”] are the necessary expression [“commands”] of the way God “is” — RPT.

One of the most important notes to mention is that once there is a third alternative, there is no longer a dilemma.

TRUE FREE THINKER

Ken Ammi of True Free Thinker deals with the many aspects of this supposed dilemma. He does an excellent job of doing this. However, zero in on the section from the 2:40 mark to the 3:45 mark (the same idea is brought up in the 6:55 through 9:55 mark of the Craig response — Craig”s audio follows Mario’s). Ken Ammi does a bang-up job below (Ammi’s article being read by someone else):

(Above audio description from YouTube) Mario’s original audio is here. Apologetic315 and TrueFreeThinker team up to put to rest the many aspects of what is perceived to be a dilemma by many first year philosophy students in the Euthyphro dialogue between two Grecian thinkers: “Essay: The Euthyphro Dichotomy by Ken Ammi“

MORE CRAIG

Here is William Lane Craig responding to some challenges in regards to the Euthyphro argument.

Here is more at CAA’s “CATECHISM”:

APPENDIX

Atheists and Morality: What I Am NOT Saying

The next few paragraphs my editor wanted me to take out. He said it repeats too much from above. He’s right to a certain extent. But it can’t be left out because many atheists I meet think I’m making an argument that I’m not making. (It’s probably my fault.) So let me spell it out as explicitly as I can.

I am not saying that you have to believe in God to be a good person or that atheists like David Silverman are immoral people.

David seems like a very nice man. And some atheists live more moral lives than many Christians.

I am also not saying that atheists don’t know morality or that you need the Bible to know basic right and wrong. Everyone knows basic right and wrong whether they believe in God or have the Bible or not. In fact, that’s exactly what the Bible teaches (see Romans 2:14-15).9

What I am saying is that atheists can’t justify morality. They can act morally and judge some actions as being moral and others immoral (as David Silverman does). But they can provide no objective basis for those judgments. Whether it’s the Holocaust, raping and murdering children, eating children, aborting children, or who adopts children, atheists have no objective standard by which to judge any of it.

Let me go out on a limb and suggest that if your worldview requires you to believe that raping children, murdering children, eating children, and slaughtering six million innocent people is just a matter of opinion, then you have the wrong worldview.

No Book Without an Author—No Morality Without God

Unlike David Silverman, Sam Harris is a new atheist who believes in objective morality. In his book, The Moral Landscape, Harris maintains that objective morality is related to “the well-being of conscious creatures,” and that science can help us determine what brings “well-being” to conscious creatures.

What’s objectionable about that thesis? Well-being is usually associated with moral choices (although not always). And science may help us discover what actually helps bring about well-being. The problem with Harris’s approach is that he is addressing the wrong question.

The question is not what method should we use to discover what is moral, but what actually makes something moral? Why does a moral law exist at all, and why does it have authority over us?

The Moral Landscape gives us no answer. It’s a nearly three-hundred-page-long example of the most common mistake made by those who think objective morality can exist without God. Harris seems to think that because we can know objective morality (epistemology), that explains why objective morality exists in the first place (ontology).

You may come to know about objective morality in many different ways: from parents, teachers, society, your conscience, etc. (Harris talks about brain states.) And you can know it while denying God exists. But that’s like saying you can know what a book says while denying there’s an author. Of course you can do that, but there would be no book to know unless there was an author! In other words, atheists can know objective morality while denying God exists, but there would be no objective morality unless God exists.

Science might be able to tell you if an action may hurt someone—like if giving a man cyanide will kill him—but science can’t tell you whether or not you ought to hurt someone. Who said it’s wrong to harm people? Sam Harris? Does he have authority over the rest of humanity? Is his nature the standard of Good?

To get his system to work, Sam Harris must smuggle in what he claims is an objective moral standard: “well-being.” As William Lane Craig pointed out in his debate with Harris, that’s not a fail-safe criterion of what’s right. But even if it was, what objective, unchanging, moral authority establishes it as right? It can’t be Sam Harris or any other finite, changing person. Only an unchanging authoritative being, who can prescribe and enforce objective morality here and beyond the grave, is an adequate standard. Only God can ground Justice and ensure that Justice is ultimately done.

Can’t Evolution Explain Morality?

We’ve already seen that an atheistic worldview can’t account for objective morality, as even Richard Dawkins once admitted. He wrote, “It’s pretty hard to get objective morality without religion.” Yet some atheists persist in claiming that evolution somehow gives us objective morality to help us survive—that if we didn’t “cooperate” with one another, we wouldn’t survive. But this argument doesn’t survive for several reasons.

First, trying to explain morality by biology is a massive category mistake. A category mistake is when you treat something in one category as if it belongs in another category. Questions like those posed earlier do that: “‘What is the chemical composition of justice?” or “What does courage taste like?” Justice and courage do not have chemicals or flavor, so the questions commit category mistakes.

The same is true when atheists try to explain moral laws by biological processes. Morality and biology are in different categories. You can’t explain an immaterial moral law by a material biological process. Justice is not made of molecules. Furthermore, moral laws are prescriptive and come from authoritative personal agents. Biological processes are descriptive and have no authority to tell you what to do. How could a mutating genetic code have the moral authority to tell you how you ought to behave?

Second, biological processes can’t make survival a moral right. There is no real “good” or purpose to evolution. Without God, survival is a subjective preference of the creature wanting to survive, but not an objective moral good or right. Biology describes what does survive, not what ought to survive. Why should humans survive as opposed to anything else? And which humans, we or the Nazis?

If one could make the case that survival is somehow a right, then should a person rape to propagate his DNA? Should a person murder if it helps him survive? Should a society murder the weak and undesirables to improve the gene pool and help the desirables survive? Hitler used evolutionary theory to justify just that.

You can’t answer those moral questions without smuggling a moral law into the evolutionary worldview. As Sam Harris rightly puts it, “Evolution could never have foreseen the wisdom or necessity of creating stable democracies, mitigating climate change, saving other species from extinction, containing the spread of nuclear weapons, or of doing much else that is now crucial to our happiness in this century.” Indeed, evolution describes a survival-of-the-fittest outcome. It doesn’t prescribe a moral outcome. That’s why Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, to their credit, are anti-Darwinian when it comes to morality. They just don’t realize that they are stealing a moral law from God when they condemn a survival-of-the-fittest ethic.

Third, physical survival isn’t the highest moral virtue. Sacrificing yourself to save someone else, as our military heroes often do, is the highest form of morality and love—far higher than mere survival. That’s exactly what Jesus claimed and then did for us.14

Fourth, since evolution is a process of change, then morals must change. Rape and murder may one day be considered “good.” So if evolution is your guide, it’s impossible for morals to be objective and unchanging.

Fifth, the assertion that evolution gave us morality as a kind of “social contract” to enable civilization isn’t an adequate ground for objective morality. ‘What if someone violates the “contract?” Is he immoral for doing so? To judge him wrong, you would again need to appeal to an objective moral law beyond any “social contract,” like we did in order to condemn the Nazi “social contract.”

Finally, the claim that we wouldn’t survive without cooperation is a pragmatic issue, not a moral issue. And it isn’t even true. Many people survive and even prosper precisely because they don’t cooperate with other people! Criminals often prosper quite nicely. So do dictators. Atheist Joseph Stalin murdered millions more people than he cooperated with. He never got justice in this life. He died comfortably in bed at the age of seventy-four, shaking his fist at God one last time.

Atheists call murderers like Stalin, Mao, and Poi Pot, who were atheists themselves, “madmen”—as if reason alone should have led them to act morally. But those dictators were very reasonably following their atheistic belief that without God, everything is permissible. Reason is a tool by which we discover what the moral law is, but it can’t account for why the moral law exists in the first place. For the moral law to exist, God must exist. If God does not exist, then why shouldn’t Stalin and Mao have murdered to get what they wanted, especially since they knew they could get away with it? That certainly was not “unreasonable.”

From Euthyphro to Elvis

“Not so fast,” say atheists. “Even if evolution doesn’t work as the standard of morality, you can’t ground objective morality in God either. You’re forgetting about the Euthyphro dilemma.”

Euthyphro is a character in one of Plato’s writings who poses a couple of questions that either make God subject to objective morality or an arbitrary source of morality. The supposed dilemma goes like this: Does God do something because it is good (which would imply there is a standard of Good beyond God), or is it Good because God does it (which would imply that God arbitrarily makes up morality)?

But this is not an actual dilemma at all. An actual dilemma has only two opposing alternatives: A or non-A. We don’t have that here. In this situation we have A and B. Well, maybe there is a third alternative: a C. There is.

When it comes to morality, God doesn’t look up to another standard beyond Himself. If He has to look up to another standard, then He wouldn’t be God—the standard beyond Him would be God. Nor is God arbitrary. There is nothing arbitrary about an unchanging standard of Good.

The third alternative is that God’s nature is the standard. God Himself is the unchanging standard of Good. The buck has to stop somewhere, and it stops at God’s unchanging moral nature. In other words, the standard of rightness we know as the Moral Law flows from the nature of God Himself—infinite justice and infinite love.

How can God’s nature account for ultimate value? Before answering that, we need to reiterate that an atheistic worldview can’t account for the objective value of human beings. On an atheistic worldview, we’re nothing but overgrown germs that arrived here accidentally by mindless processes and thus have no ultimate purpose or significance. Life is meaningless. We are each objectively worth zero. And adding a bunch of us up into a society doesn’t create value. If you add up a bunch of zeroes, the total worth is still zero.

But on a Christian worldview, God is the ground and source of ultimate value, and He endows us with His image. Therefore, our lives have objective value, meaning, and purpose. If there is a real purpose to life—a “final cause” as Aristotle put it—then there must be a right way to live it. After all, to get to a specific destination, you can’t just go in any direction. Morality helps inform us of that direction. That means God doesn’t arbitrarily make up moral commands. He’s not an exasperated parent who justifies everything with, “Just do it because I said so!” God’s commands are consistent with His moral nature and point us to the final cause or objective goal of our lives (more on that goal later).

So the source of our lives as human beings is God, not primordial slime. And source is important. You can see the importance of source by considering the most expensive items ever sold at auction:

- The most expensive lock of hair: Elvis Presley’s, $115,000.

- The most expensive piece of clothing: Marilyn Monroe’s “Happy Birthday Mr. President” dress, $1,267,500.

- The most expensive piece of sports memorabilia: Mark McGwire’s 70th-home-run ball from 1998, $3,000,000.

People ascribed enormous value to those items not because the raw materials are that valuable—you can get hair, dresses, and baseballs for a lot less—but because of the source of each item. People or events that are deemed special are connected with those items.

The values of those items are extrinsic in that they are ascribed by whatever the buyers want to pay. But if Christianity is true, your value is intrinsic because you are connected to God. Your value is based on the worth infused into you by the source and standard of all value, God Himself.

Marinate in that for a minute: The infinite God has endowed you with immeasurable worth. The majestic heavens aren’t made in His image, but you are! That’s why you have moral rights. As Thomas Jefferson put it, “All men are created equal [and] are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Because of God, you are inherently valuable, and always will be, no matter what you’ve done or what anyone else thinks about you. Your value is far from zero. You are literally sacred.

- Frank Turek, Stealing from God (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2014), 98-106.