Is the U.S. tax system fair? Are the rich paying too little or too much? What about the middle and lower class? New York Times bestselling author Amity Shlaes answers these questions, and offers a tax solution that most Americans could get on board with.

Prager U

Killing the American Dream

Hat-Tip to WINTERY KNIGHT:

…Where are the jobs for the young people supposed to come from, when the young people keep voting against the private sector businesses that create jobs? I don’t know that their parents and professors are explaining to them how the economy works. Taxes and regulations make job creation harder, and then you have nowhere to work, and just live at home.

The “weak job opportunities” that Pew Research mentioned are especially weak for young people who graduate from non-STEM programs. STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) graduates are able to find jobs that pay enough. Liberal arts graduates end up serving coffee. And then they vote for more environmentalist regulations and a higher minimum wage, and find themselves out of a job entirely. The jobs just go elsewhere where there are lower taxes and fewer regulations.

It’s really important for young people to get into the workforce early and start building their resume and references with work experience. Two years of work experience is better than graduate school in most cases, too. Saving works much better when you start investing early, so watch your spending.

The American Dream is real, but it may not be for much longer. What exactly is the American Dream? And why is it in danger? Elaine Parker of Job Creators Network explains. Find out more about Job Creators Network and Information Station! https://informationstation.org/

What Every High School Principal Should Say

If every high school principal said this, it would change students’ lives and would change America. So what exactly should every high school principal say? Dennis Prager explains.

Are the Police Racist?

Are the police racist? Do they disproportionately shoot African-Americans? Are incidents in places like Ferguson and Baltimore evidence of systemic discrimination? Heather Mac Donald, a scholar at the Manhattan Institute, explains.

- See also my upload via Jason Riley interviewing Heather Mac Donald

Socialism Makes People Selfish ~ PragerU

Which is better: socialism or capitalism? Does one make people kinder and more caring, while the other makes people greedy and more selfish? In this video, Dennis Prager explains the moral differences between socialism and capitalism, and why anyone who wants a kind and generous society must support one and oppose the other.

Why Don’t Feminists Fight for Muslim Women? Culture Counts

Are women oppressed in Muslim countries? What about in Islamic enclaves in the West? Are these places violating or fulfilling the Quran and Islamic law? Ayaan Hirsi Ali, an author and activist who was raised a devout Muslim, describes the human rights crisis of our time, asks why feminists in the West don’t seem to care, and explains why immigration to the West from the Middle East means this issue matters more than ever.

Love Me Some Kreeft! (The Benefits of Belief)

Even if you don’t believe in God, do you wish you did? Even if you’re an atheist or an agnostic, is there still good reason to act religiously? Peter Kreeft, philosophy professor at Boston College, explains why even atheists should want there to be a God, and how acting as if there is one may actually lead to you believing it.

Who’s More Pro-Choice: Europe or America?

Are abortion laws more conservative in America or in Western Europe? Would a pregnant woman seeking an abortion have an easier time getting one in Texas or in…Germany? The answers, as talk show host Elisha Krauss explains, may just change how you think about America’s abortion laws.

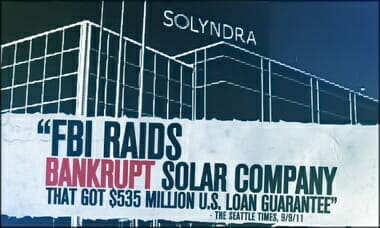

Government Investing A Recipe for Failure

- “A fundamental principle of information theory is that you can’t guarantee outcomes… in order for an experiment to yield knowledge, it has to be able to fail. If you have guaranteed experiments, you have zero knowledge” ~ George Gilder

Interview by Dennis Prager {Editors note: this is how the USSR ended up with warehouses FULL of “widgets” (things made that it could not use or people did not want) no one needed in the real world. This economic law enforcers George Gilder’s contention that when government supports a venture from failing, no information is gained in knowing if the program actually works. Only the free-market can do this.}

From transportation to energy, and everything in between, should the government invest money in as many promising projects as possible? Or would that actually doom many of those ventures to failure? Burt Folsom, historian and professor at Hillsdale College, answers those questions by drawing on the fascinating history of the race to build America’s railroads and airplanes.

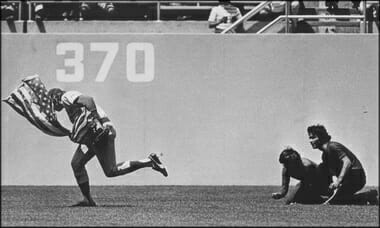

Baseball and American Culture

Rick Monday was honored by throwing out the first pitch at Monday’s game at Chavez Ravine for arguably the greatest save in Dodgers Stadium history.

What, you say, Monday was an outfielder? And why would he be credited with a save?

Forty years ago on April 25, Monday was playing centerfield for the Cubs in a game against the Dodgers.

The game turned from an ordinary early season game into one with high drama when two people suddenly appeared in the outfield at Dodger Stadium.

Legendary Dodgers announcer Vin Scully said, “”It looks like he’s going to burn a flag!”

One had an American flag. The other, lighter fluid and was planning on burning Old Glory. This was an act Monday, who served in the Marine Corps, was not about to let happen….

The scoreboard operator was swift at the button, punching up: “Rick Monday — You Made a Great Play.”…

Is There a Campus Rape Culture?

Is it true that 1 in 5 women are raped on America’s college campuses? If so, what does that say about our universities and the people who run them? If not, how did that statistic get into the mainstream? Caroline Kitchens, Senior Research Associate at the American Enterprise Institute, looks at the data and explains the very significant results.

Government: Is it Ever Big Enough?

Can the government ever be too big? How much spending is enough spending? And if there can be too much spending, where is that point? William Voegeli, Senior Editor of the Claremont Review of Books, explores these complex questions and offers some clear answers.