A “PART TWO” to this post is this one:

(Originally posted in 2015 after a conversation with a J-Dub at Starbucks, video file updated)

In Bobby Conway’s post over at ONE MINUTE APOLOGIST, he notes the following:

How can we reply to a Jehovah’s Witness? It’s not necessary to translate Greek nouns lacking an article as indefinite. Even Jehovah’s Witnesses aren’t consistent here. Rather, they use the indefinite article when it’s convenient to fit their theology. If they were consistent in their New World Translation, they’d have to utilize a before God in several other spots, even within John 1. For example, what do John 1:6, 1:12, 1:13, and 1:18 have in common? They’re all missing a definite article in the Greek before the word God. If Jehovah’s Witnesses were to translate these verses using the indefinite article, here’s how they would read:

- “There came a man who was sent from a God” (John 1:6).

- “He gave the right to become Children of a God” (John 1:12).

- “Who were born…of a God” (John 1:13).

- “No one has ever seen a God” (John 1:18).

As you can see, this would be a theological game changer. Jehovah’s Witnesses aren’t facing the facts. And the fact is, Jesus is divine. He’s God in the flesh. Here’s a clear example of where cultic apologetics are won or lost in the Greek. The original languages don’t reveal a Jesus who is a god; rather, they reveal a Jesus who is God. It’s not the article (necessarily) that determines the translation of the word. It’s the context. Once Jesus becomes anything less than fully God and fully man, we’ve become a cult. Next time you talk to a Jehovah’s Witness, remember, words matter, especially when talking about the Word.

[I add some more examples:]

- Matt 5:9 | Happy are the peacemakers, since they will be called sons of A God.

- Matt 6:24 | No one can slave for two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will stick to the one and despise the other. You cannot slave for A God and for Riches.

- Luke 1:35 | In answer the angel said to her: “Holy spirit will come upon you, and power of the Most High will overshadow you. And for that reason the one who is born will be called holy, A God’s Son.

- Luke 2:40 | And the young child continued growing and getting strong, being filled with wisdom, and A God’s favor continued upon him.

- John 1:6 | There came a man who was sent as a representative of A God; his name was John

- John 1:12, 13 | However, to all who did receive him, he gave authority to become A God’s children. And they were born, not from blood or from a fleshly will or from man’s will, but from A God. This one came to him in the night+ and said to him: “Rabbi, we know that you have come from God as a teacher, for no one can perform these signs that you perform unless A God is with him.”

- John 3:21 | But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that his works may be made manifest as having been done in harmony with A God.”

- John 9:16 | Some of the Pharisees then began to say: “This is not a man from A God, for he does not observe the Sabbath.” Others said: “How can a man who is a sinner perform signs of that sort?” So there was a division among them.

- John 9:33 | “If this man were not from A God, he could do nothing at all.”

- Rom 1:7 | to all those who are in Rome as A God’s beloved ones, called to be holy ones:

- Rom 1:17-18 | For in it A God’s righteousness is being revealed by faith and for faith, just as it is written: “But the righteous one will live by reason of faith.” For A God’s wrath is being revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men who are suppressing the truth in an unrighteous way,

- 1 Cor 1:30 | But it is due to him that you are in union with Christ Jesus, who has become to us wisdom from A God, also righteousness and sanctification and release by ransom,

- Phil 2:11 | and every tongue should openly acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord to the glory of A God the Father

- Phil 2:13 | For A God is the one who for the sake of his good pleasure energizes you, giving you both the desire and the power to act.

- Titus 1:1 | Paul, a slave of A God and an apostle of Jesus Christ according to the faith of God’s chosen ones and the accurate knowledge of the truth that is according to godly devotion.

I realized — after posting on an encounter with a Jehovah’s Witness at Starbucks — that I do not have a lot posted on Jehovah’s Witnesses. I do on Mormonism, but not J-Dubs. (During the Iraq War Democrats called President George W. Bush, “Dubya.” I liked this shortening of his name for conversation ease. I transferred this ease over to Jehovah’s Witnesses as “J-Dub.”). So I will post some information via discussions I have had (on-line) over the years. The one I will clean up and post here deals with a quick presentation I give when a J-Dub is in front of a doughnut or coffee shop. All you have to do is memorize John 17:3, John 1:1… and where to go to enforce your point if conversation continues… but still have to get to work.

…The best way to dial in a cult is to see who they say Jesus is. In Orthodox Christian theology, Christ is eternal. Jesus is best reflected by this statement: He always was, He always is, and He always will be… Unmoved, Unchanged, Undefeated, and never Undone!

But in LDS (Mormon) theology, Jesus was born in heaven via sexual relations between Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother; Lucifer is Jesus’ brother, born also via sexual relations between Heavenly Father and one of his many wives. So, in fact he is not eternal. Heavenly Father, e.g., God, was once a man as well. Prior to Heavenly Father being a man, he was born in a heaven to parents as well (he was born via sexual relations in a heaven and a earth). Therefore, in LDS theology, even Heavenly Father isn’t eternal. Nor is he unchanging – physically or spiritually – because he was once a man who had to follow a path to becoming his own God. Also, if Heavenly Father was born to parents, who were themselves born to parents, etc., etc.. Who were the first parents? How did they get here?

Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that the first creative act by God – Jehovah – was to create Michael the Archangel. It was Michael who came to earth as Jesus, and after went back to heaven as Michael. Both Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses do not believe that Jesus’ death on the cross was for their sins. His death was merely for Adam’s original sin, therefore, the Mormon or Jehovah’s Witness must earn their own salvation by doing good works to attain entrance into heaven. Christianity teaches that nothing man can do can please God. He is infinitely good, we are not. This is why Jesus’ sacrifice is so important to Christians: he lived the life we never could.

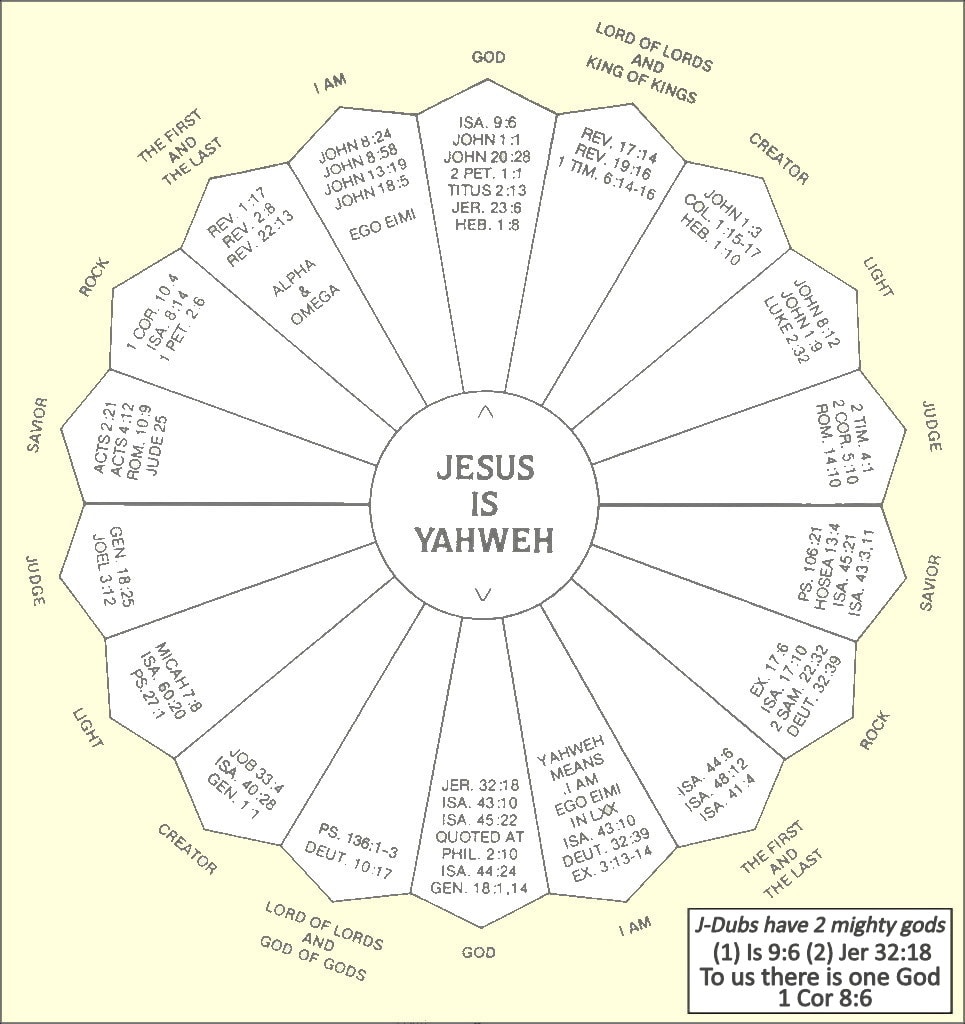

Okay, let me give you a quick refutation to share with the Jehovah’s Witness when they are at your door. Jehovah’s Witnesses are very adamant that they are monotheists, that is, they believe in one God. We do also, but we understand this one God as a trinity… do not get into the Trinity with them, this is the one subject they study the most. It takes a trained professional like me to refute their attacks on this doctrine.

You can ask them to turn to one of their favorite verses in their own bible (New World Translation), which is John 17:3:

- This means everlasting life, their taking in knowledge of you [Greek: that they may know you], the only true God, and of the one whom you sent forth, Jesus Christ (NWT).

At this point you can ask them if Jehovah is the only true God. Make the point that any other God would be a false God, ask them: so people who believe in a God other than Jehovah believe in a false God?

At this point, when you get them to agree with you that there is only one true God, ask them to turn to John 1:1, which reads:

- In [the] beginning the Word was, and the Word was with God, and the Word was a God (NWT).

This is the clincher. Ask them if Jesus is a false God or a true God. Our Bible doesn’t put the athat I underlined; the Greek literally calls Jesus God Almighty. They may want to change the subject, or the like. Just keep pressing the issue – politely – that according to their own Bible they are polytheists (a person who believes in multiple gods), and are not monotheists…

Here is a conversion by an evangelist at a Jehovah’s Witness convention where the idea of John 1:1 and 17:3 are fleshed out:

Remember, J-Dubs consider themselves rabidly monotheistic, but as one scholar says below, “…It must be stated quite frankly that, if the Jehovah’s Witnesses take this translation seriously, they are polytheists.” Here is another conversation where the J-Dubs “multiple gods” view is applied to creation (from the 5:12 mark). And of course a CLASSIC presentation by the late/great Walter Martin.

The verses that one should be familiar with are used in the conversation on John 8:58-59. Both verses are worth memorizing defenses of, but the area I want to focus on are the Old Testament verses used in this discussion:

Gordon, Jesus clearly states He is God in John 8:58-59. It doesn’t need any explaining to a first century Jew. But to a 21st century honky (western-Caucasian man / a white boy / cracker), it does need explaining. And as you can see, the first century Jews tried to stone Jesus for claiming such (John 8:59 and John 10:31-33). The first century Jew could not stone a man for claiming to be “in one mind,” or in “the same step” as God. They could only stone him for the blasphemy of claiming to be God, not a god.

John 8:58 needs no explaining if you are familiar with the Bible. But if you are not, and do not understand Exodus 3:14, then you would have to have an explanation. But since you apparently understand Exodus 3:14, then you understand Jesus clear claim to be God. So you have corrected yourself.

In fact, this is what the ENTIRE trial of Jesus was about?! He was on trial for claiming to be God, and this claim eventually led to His crucifixion (Zechariah 12:10).

The talk of who God is should be consolidated as to create more room on the board for the other members.

- “See now that I, I am He, and there is no God besides Me” (Deuteronomy 32:39 NASB)

- “Before Me there was no God formed, and there will be none after me” (Isaiah 43:10 NASB)

- “Is there any God besides Me, or is there any other Rock? I know of none” (Isaiah 44:8 NASB)

- “I am the Lord, and there is no other; besides Me there is no God” (Isaiah 45:5 NASB)

So it seems quite clear that when Jesus is called God, or even “a God” in John 1:1 (which John 17:3 says there is only One true God) – and is worshipped like God (which Matthew 4:10 reserves only for the One true God) – one must scratch his head in perplexity.

Are Jehovah’s Witnesses polytheists? They claim not to be, they claim to be monotheists. Mormons are polytheists, or more precisely – henotheists, they admit such (another example of why they are considered outside the “pale of orthodoxy”). The dilemma is (referencing John 17:3) that Jehovah Witnesses have two gods, and this cannot be reconciled with Deuteronomy 32:39 that “there is no God besides me;” or, John 17:3 which states “that they might know thee the only true God;” as well as God almighty calling Jesus God almighty in Hebrews 1:8-10. Alternatively Jesus clear statement to his deity (Godship) in John 8:58 and Matthew 22:41-46 (Jesus Himself making the comparison to Psalm 110:1).

When I talk to JW’s or LDS I drive the point home that Jesus would be a false god if he weren’t “God.” But this is something they can’t accept either… so the Bible must be wrong? But contrary to what Gordon says, Jesus clearly defined himself as – not a God – but thee God of the Shema.

And from Let Us Reason’s site, we find a list of leading and well-respected Greek language scholars ~ some even being quoted at one time as supporting the J-Dubs version in their own publications. I will embolden their names:

WHAT DO GREEK SCHOLARS THINK ABOUT JEHOVAH’S WITNESS TRANSLATION OF JOHN 1:1?

- Dr. J. J. Griesback: “So numerous and clear are the arguments and testimonies of Scriptures in favor of the true Deity of Christ, that I can hardly imagine how, upon the admission of the Divine authority of Scripture, and with regard to fair rules of interpretation, this doctrine can by any man be called in doubt. Especially the passage John 1:1 is so clear and so superior to all exception, that by no daring efforts of either commentators or critics can it be snatched out of the hands of the defenders of the truth.”

- Dr. Eugene A. Nida (Head of the Translation Department of the American Bible Society Translators of the GOOD NEWS BIBLE): “With regard to John 1:1 there is, of course, a complication simply because the NEW WORLD TRANSLATION was apparently done by persons who did not take seriously the syntax of the Greek”. (Bill and Joan Cetnar Questions for Jehovah’s Witnesses “who love the truth” p..55

- Dr. William Barclay (University of Glasgow, Scotland): “The deliberate distortion of truth by this sect is seen in their New Testament translations. John 1:1 translated:’. . . the Word was a god’.a translation which is grammatically impossible. It is abundantly clear that a sect which can translate the New Testament like that is intellectually dishonest. THE EXPOSITORY TIMES Nov, 1985

- Dr. B. F. Westcott (Whose Greek text [pictured on the left of the graphic which is to the right] is used in JW KINGDOM INTERLINEAR [the NWT text is to the right of Westcott’s Greek text …click to enlarge]): “The predicate (God) stands emphatically first, as in 4:24. It is necessarily without the article… No idea of inferiority of nature is suggested by the form of expression, which simply affirms the true Deity of the Word… in the third clause `the Word’ is declared to be `God’ and so included in the unity of the Godhead.”

The Gospel According to St. John (Eerdmans,1953- reprint) p. 3, (The Bible Collector, July-December, 1971, p. 12.).

“Numerous scholars with true credentials in the Biblical languages have condemned the Watchtower’s New World Translation as a fatal distortion of God’s written Word. For example, see The Bible Collector (July-December, 1971) issue which devotes three articles evaluating the Watchtower scripture.” ~ UK Apologetics

- Dr. Anthony Hoekema, commented: Their New World Translation of the Bible is by no means an objective rendering of the sacred text into Modern English, but is a biased translation in which many of the peculiar teachings of the Watchtower Society are smuggled into the text of the Bible itself (The Four Major Cults, pp. 238, 239].

- Dr. Ernest C. Colwell (University of Chicago): “A definite predicate nominative has the article when it follows the verb; it does not have the article when it precedes the verb; . . .this statement cannot be regarded as strange in the prologue of the gospel which reaches its climax in the confession of Thomas. `My Lord and my God.’ ” John 20:28

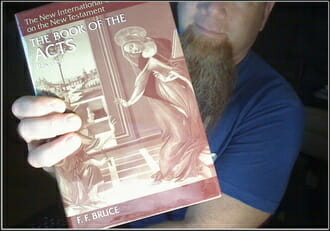

- Dr. F. F. Bruce (University of Manchester, England): “Much is made by Arian amateur grammarians of the omission of the definite article with `God’ in the phrase `And the Word was God’. Such an omission is common with nouns in a predicate construction. `a god’ would be totally indefensible.”

- Dr. Paul L. Kaufman (Portland OR.): “The Jehovah’s Witness people evidence an abysmal ignorance of the basic tenets of Greek grammar in their mistranslation of John 1:1.”

- Dr. Charles L. Feinberg (La Mirada CA.): “I can assure you that the rendering which the Jehovah’s Witnesses give John 1:1 is not held by any reputable Greek scholar.”

- Dr. Robert Countess, who wrote a doctoral dissertation on the Greek text of the New World Translation, concluded that the The Christ of the New World Translation “has been sharply unsuccessful in keeping doctrinal considerations from influencing the actual translation …. It must be viewed as a radically biased piece of work. At some points it is actually dishonest. At others it is neither modern nor scholarly “78 No wonder British scholar H.H. Rowley asserted, “From beginning to end this volume is a shining example of how the Bible should not be translated.”79 Indeed, Rowley said, this translation is “an insult to the Word of God.”

- Dr. Harry A. Sturz: (Dr. Sturz is Chairman of the Language Department and Professor of Greek at Biola College) “Therefore, the NWT rendering: “the Word was a god” is not a “literal” but an ungrammatical and tendential translation. A literal translation in English can be nothing other than: “the word was God.” THE BIBLE COLLECTOR July – December, 1971 p. 12

- Dr. J. Johnson of California State University, Long Beach. When asked to comment on the Greek, said, “No justification whatsoever for translating theos en ho logos as ‘the Word was a god’. There is no syntactical parallel to Acts 23:6 where there is a statement in indirect discourse. Jn.1:1 is direct.. I am neither a Christian nor a Trinitarian.

DO ANY REPUTABLE GREEK SCHOLARS AGREE WITH THE NEW WORLD TRANSLATION OF JOHN 1:1?

- A. T. Robertson: “So in John 1:1 theos en ho logos the meaning has to be the Logos was God, -not God was the Logos.” A New short Grammar of the Greek Testament, AT. Robertson and W. Hersey Davis (Baker Book House, p. 279.

- E. M. Sidebottom:”…the tendency to write ‘the Word was divine’ for theos en ho Iogos springs from a reticence to attribute the full Christian position to john. The Christ of the Fourth Gospel (S.P.C.K., 1961), p. 461.

- C. K. Barrett: “The absence of the article indicates that the Word is God, but is not the only being of whom this is true; if ho theos had been written it would have implied that no divine being existed outside the second person of the Trinity.” The Gospel According to St. John (S.P.C.K., 1955), p. 76.

- C. H. Dodd: “On this analogy, the meaning of _theos en ho logos will be that the ousia of ho logos, that which it truly is, is rightly denominated theos… That is the ousia of ho theos (the personal God of Abraham,) the Father goes without saying. In fact, the Nicene homoousios to patri is a perfect paraphrase.” “New Testament Translation Problems the bible Translator, 28, 1 (Jan. 1977), P. 104.

- Randolph 0. Yeager: “Only sophomores in Greek grammar are going to translate ..and the Word was a God.’ The article with logos, shows that to logos is thesubject of the verb en and the fact that theos is without the article designates it as the predicate nominative. The emphatic position of theos demands that we translate ‘…and the Word was God.’ John is not saying as Jehovah’s Witnesses are fond of teaching that Jesus was only one of many Gods. He is saying precisely the opposite.” The Renaissance New Testament, Vol. 4 (Renaissance Press, 1980), P. 4.

- Henry Alford: “Theos must then be taken as implying God, in substance and essence,–not ho theos, ‘the Father,’ in person. It noes not = theios; nor is it to be rendered a God–but, as in sarx engeneto, sarx expresses that state into which the Divine Word entered by a-definite act, so in theos en, theos expresses that essence which was His en arche:–that He was very God . So that this first verse must be connected thus: the Logos was from eternity,–was with God (the Father),–and was Himself God.” (Alford’s Greek Testament: An Exegetical and Critical Commentary, Vol. I, Part II Guardian ‘press 1976 ; originally published 1871). p. 681.

- Donald Guthrie: “The absence of the article with Theos has misled some into t inking teat the correct understanding of the statement would be that ‘the word was a God’ (or divine), but this is grammatically indefensible since Theos is a predicate.” New Testament Theology (InterVarsity Press, 1981), p. 327.

- Bruce M. Metzger, Professor of New Testament Language and literature at Princeton Theological Seminary said: “Far more pernicious in this same verse is the rendering, . . . `and the Word was a god,’ with the following footnotes: ” `A god,’ In contrast with `the God’ “. It must be stated quite frankly that, if the Jehovah’s Witnesses take this translation seriously, they are polytheists. In view of the additional light which is available during this age of Grace, such a representation is even more reprehensible than were the heathenish, polytheistic errors into which ancient Israel was so prone to fall. As a matter of solid fact, however, such a rendering is a frightful mistranslation.” “The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Jesus Christ,” Theology Today (April 1953), p. 75.

- James Moffatt: “‘The Word was God . . .And the Word became flesh,’ simply means he Word was divine . . . . And the Word became human.’ The Nicene faith, in the Chalcedon definition, was intended to conserve both of these truths against theories that failed to present Jesus as truly God and truly man ….” Jesus Christ the Same (Abingdon-Cokesbury, 1945), p. 61.

- E. C. Colwell: “…predicate nouns preceding the verb cannot be regarded as indefinite -or qualitative simply because they lack the article; it could be regarded as indefinite or qualitative only if this is demanded by the context,and in the case of John l:l this is not so.” A Definite Rule for the Use of the Article in the Greek New Testament,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 52 (1933), p. 20.

- Philip B. Harner: “Perhaps the clause could be translated, ‘the Word had the same nature as God.’ This would be one way of representing John’s thought, which is, as I understand it,”that ho logos, no less than ho theos, had the nature of theos.””(Qualitative Anarthrous Predicate Nouns Mark 15:39 and John 1:1,” journal of Biblical Literature, 92, 1 (March 1973), p. 87.

- Philip Harner states in the Journal of Biblical Literature, 92, 1 (March 1973) on Jn.1:1 “In vs. 1c the Johannine hymn is bordering on the usage of ‘God’ for the Son, but by omitting the article it avoids any suggestion of personal identification of the Word with the Father. And for Gentile readers the line also avoids any suggestion that the Word was a second God in any Hellenistic sense.” (pg. 86. Harner notes the source of this quote: Brown, John I-XII, 24)

- Julius R. Mantey: “Since Colwell’s and Harner’s article in JBL, especially that of Harner, it is neither scholarly nor reasonable to translate John 1:1 ‘The Word was a god.’ Word-order has made obsolete and incorrect such a rendering …. In view of the preceding facts, especially because you have been quoting me out of context, I herewith request you not to quote the Manual Grammar of the Greek New Testament again, which you have been doing for 24 years.” Letter from Mantey to the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society. “A Grossly Misleading Translation …. John 1:1, which reads ‘In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God,’ is shockingly mistranslated, ‘Originally the Word was, and the Word was with God, and the Word was a god,’ in a New World Translation of the Christian Greek Scriptures, published under the auspices o Jehovah’s Witnesses.” Statement JR Mantey, published in various sources.

COMMENTARY:

1) In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. This One was in the beginning with God. Even the first readers of John’s Gospel must have noted the resemblance between the first phrase ἐν ἀρχῇ, “in the beginning,” and that with which Moses begins Genesis. This parallel with Moses was, no doubt, intentional on John’s part. The phrase points to the instant when time first began and the first creative act of God occurred. But instead of coming down from that first instant into the course of time, John faces in the opposite direction and gazes back into the eternity before time was. We may compare John 17:5; 8:58, and possibly Rev. 3:14, but scarcely ἀπʼ ἀρχῆς in Prov. 8:23, for in this passage “from the beginning” refers to Wisdom, a personification, of which v. 25 reports: “I was brought forth,” something that is altogether excluded as regards the divine person of the Logos.

In the Greek many phrases lack the article, which is not considered necessary, R. 791; so John writes ἐν ἀρχῇ. But in John’s first sentence the emphasis is on this phrase “in the beginning” and not on the subject “the Word.” This means that John is not answering the question, “Who was in the beginning?” to which the answer would naturally be, “God”; but the question, “Since when was the Logos?” the answer to which is, “Since all eternity.” This is why John has the verb ἦν, “was,” the durative imperfect, which reaches back indefinitely beyond the instant of the beginning. What R. 833 says about a number of doubtful imperfects, some of which, though they are imperfect in form are yet used as aorists in sense, can hardly be applied in this case. We, of course, must say that the idea of eternity excludes all notions of tense, present, past, and future; for eternity is not time, even vast time, in any sense but the absolute opposite of time—timelessness. Thus, strictly speaking, there is nothing prior to “the beginning,” and no duration or durative tense in eternity. In other words, human language has no forms of expression that fit the conditions of the eternal world. Our minds are chained to the concepts of time. Of necessity, then, when anything in eternity is presented to us, it must be by such imperfect means as our minds and our language afford. That is why the durative idea in the imperfect tense ἦν is superior to the punctiliar aoristic idea: In the beginning the Logos “was,” ein ruhendes und waehrendes Sein (Zahn)—“was” in eternal existence. All else had a beginning, “became,” ἐγένετο, was created; not the Logos. This—may we call it—timeless ἦν in John’s first sentence utterly refutes the doctrine of Arius, which he summed up in the formula: ἦν ὅτε οὑκ ἦν, “there was (a time) when he (the Son) was not.” The eternity of the Logos is co-equal with that of the Father.

Without a modifier, none being necessary for John’s readers and hearers, he writes ὁ λόγος, “the Word.” This is “the only-begotten Son which is in the bosom of the Father,” v. 18. “The Logos” is a title for Christ that is peculiar to John and is used by him alone. In general this title resembles many others, some of them being used also by Christ himself, such as Light, Life, Way, Truth, etc. To imagine that the Logos-title involves a peculiar, profound, and speculative Logos-doctrine on the part of John is to start on that road which in ancient times led to Gnosticism and in modern times to strange views of the doctrine concerning Christ. We must shake off, first of all, the old idea that the title “Logos” is in a class apart from the other titles which the Scriptures bestow upon Christ, which are of a special profundity, and that we must attempt to penetrate into these mysterious depths. This already will release us from the hypothesis that John borrowed this title from extraneous sources, either with it to grace his own doctrine concerning Christ or to correct the misuse of this title among the churches of his day. Not one particle of evidence exists to the effect that in John’s day the Logos-title was used for Christ in the Christian churches in any false way whatever. And not one particle of evidence exists to the effect that John employed this title in order to make corrections in its use in the church. The heretical perversions of the title appear after the publication of John’s Gospel.

Philo’s and the Jewish-Alexandrian doctrine of a logos near the time of Christ has nothing to do with the Logos of John. Philo’s logos is in no sense a person but the impersonal reason or “idea” of God, a sort of link between the transcendent God and the world, like a mental model which an artist forms in his thought and then proceeds to work out in some kind of material. This logos, formed in God’s mind, is wholly subordinate to him, and though it is personified at times when speaking of it, it is never a person as is the Son of God and could not possibly become flesh and be born a man. Whether John knew of this philosophy it is impossible for us to say; he himself betrays no such knowledge.

As far as legitimate evidence goes, it is John who originated this title for Christ and who made it current and well understood in the church of his day. The observation is also correct that what this title expressed in one weighty word was known in the church from the very start. John’s Logos is he that is called “Faithful and True” in Rev. 19:11; see v. 13: “and his name is called The Word of God.” He is identical with the “Amen, the faithful and true witness,” in Rev. 3:14; and the absolute “Yea,” without a single contradictory “nay” in the promises of God in 2 Cor. 1:19, 20, to whom the church answers with “Amen.” This Logos is the revealed “mystery” of God, of which Paul writes Col. 1:27; 2:2; 1 Tim. 3:16; which he designates explicitly as “Christ.” These designations go back to the Savior’s own words in Matt. 11:27; 16:17. Here already we may define the Logos-title: the Logos is the final and absolute revelation of God, embodied in God’s own Son, Jesus Christ. Christ is the Logos because in him all the purposes, plans, and promises of God are brought to a final focus and an absolute realization.

But the thesis cannot be maintained that the Logos-title with its origin and meaning is restricted to the New Testament alone, in particular to the Son incarnate, and belongs to him only as he became flesh. When John writes that the Logos became flesh, he evidently means that he was the Logos long before he became flesh. How long before we have already seen—before the beginning of time, in all eternity. The denial of the Son’s activity as the Logos during the Old Testament era must, therefore, be denied. When John calls the Son the Logos in eternity, it is in vain to urge that v. 17 knows only about Moses for the Old Testament and Christ as the Logos only for the New. Creation takes place through the Logos, v. 3; and this eternal Logos is the life and light of men, v. 4, without the least restriction as to time (New as opposed to Old Testament time). The argument that this Logos or Word “is spoken” and does not itself “speak” is specious. This would require that the Son should be called ὁ λεγόμενος instead of ὁ λόγος. The Logos is, indeed, spoken, but he also speaks. As being sent, given, brought to us we may stress the passive idea; as coming, as revealing himself, as filling us with light and life, the active idea is just as true and just as strong.

This opens up the wealth of the Old Testament references to the Logos. “And God said, Let there be light,” Gen. 1:4. “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness,” Gen. 1:26. “Through faith we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God,” Heb. 11:3. “By the word of the Lord were the heavens made.… For he spake, and it was done; he commanded, and it stood fast,” Ps. 33:6 and 9. “He sent his word,” Ps. 107:20; 147:15. These are not mere sounds that Jehovah uttered as when a man utters a command, and we hear the sound of his words. In these words and commands the Son stands revealed in his omnipotent and creative power, even as John says in v. 3: “All things were made by him.” This active, omnipotent revelation “in the beginning” reveals him as the Logos from all eternity, one with the Father and the Spirit and yet another, namely the Son.

He is the Angel of the Lord, who meets us throughout the Old Testament from Genesis to Malachi, even “the Angel of the Presence,” Isa. 63:9. He is “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature: for by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by him, and for him: and he was before all things, and by him all things consist. And he is the head of the body, the church: who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence. For it pleased the Father, that in him should all fulness dwell,” Col. 1:15–19. This is the revelation of the Logos in grace. The idea that by the Logos is meant only the gospel, or the gospel whose content is Christ, falls short of the truth. “Logos” is a personal name, the name of him “whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting,” Micah 5:2. And so we define once more, in the words of Besser, “The Word is the living God as he reveals himself, Isa. 8:22; Heb. 1:1, 2.” Using a weak human analogy, we may say: as the spoken word of a man is the reflection of his inmost soul, so the Son is “the brightness of his (the Father’s) glory, and the express image of his person,” Heb. 1:3. Only of Jesus as the Logos is the word true, “He that hath seen me hath seen the Father,” John 16:9; and that other word, “I and my Father are one,” John 10:30.

And the Word was with God, πρὸς τὸν θεόν. Here we note the first Hebrew trait in John’s Greek, a simple coordination with καί, “and,” followed in a moment by a second. The three coordinate statements in v. 1 stand side by side, and each of the three repeats the mighty subject, “the Word.” Three times, too, John writes the identical verb ἦν, its sense being as constant as that of the subject: the Logos “was” in all eternity, “was” in an unchanging, timeless existence. In the first statement the phrase “in the beginning” is placed forward for emphasis; in the second statement the phrase “with God” is placed at the end for emphasis.

In the Greek Θεός may or may not have the article, for the word is much like a proper noun, and in the Greek this may be articulated, a usage which the English does not have. Cases in which the presence or the absence of the article bears a significance we shall note as we proceed. The preposition πρός, as distinct from ἐν, παρά, and σύν, is of the greatest importance. R. 623 attempts to render its literal force by translating: “face to face with God.” He adds 625 that πρός is employed “for living relationship, intimate converse,” which well describes its use in this case. The idea is that of presence and communion with a strong note of reciprocity. The Logos, then, is not an attribute inhering in God, or a power emanating from him, but a person in the presence of God and turned in loving, inseparable communion toward God, and God turned equally toward him. He was another and yet not other than God. This preposition πρός sheds light on Gen. 1:26, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.”

Now comes the third statement: And the Word was God. In English we place the predicate last, while in the Greek it is placed first in order to receive the fullest emphasis. Here Θεός must omit the article thus making sure that we read it as the predicate and not as the subject, R. 791. “ ‘The Word was with God.’ This sounds, speaking according to our reason, as though the Word was something different from God. So he turns about, closes the circle, and says, ‘And God was the Word.’ ” Luther. God is the Word, God himself, fully, completely, without diminution, in very essence. What the first statement necessarily involves when it declares that already in the beginning the Word was; what the second statement clearly involves when it declares the eternal reciprocal relation between the Word and God—that is declared with simple directness in the third statement when the Word is pronounced God with no modifier making a subtraction or limitation. And now all is clear; we now see how this Word who is God “was in the beginning,” and how this Word who is God was in eternal reciprocal relation with God. This clarity is made perfect when the three ἦν are seen to be eternal, shutting out absolutely a past that in any way is limited. The Logos is one of the three divine persons of the eternal Godhead.

2) And now the three foregoing sentences are joined into one: This One was in the beginning with God. Just as we read “the Word,” “the Word,” “the Word,” three times, like the peals of a heavenly bell, like a golden chord on an organ not of earth sounding again and again, so the three rays of heavenly light in the three separate sentences fuse into one—a sun of such brightness that human eyes cannot take in all its effulgence. “It is as if John, i.e., the Spirit of God who reveals all this to him, meant to bar from the beginning all the attempts at denial which in the course of dogmatical and historical development would arise; as though he meant to say: I solemnly repeat, The eternal Godhead of Christ is the foundation of the church, of faith, of true Christology!” G. Mayer.

The Greek has the handy demonstrative οὗτος with which it sums up emphatically all that has just been said concerning a subject. In English we must use a very emphatic “he” or some equivalent like “this One,” “the Person,” or “the same” (our versions), although these equivalents are not as smooth and as idiomatic as οὗτος is in the Greek. Verse 2 does not intend to add a new feature regarding the Logos; it intends, by repeating the two phrases from the first two sentences, once more with the significant ἦν, to unite into a single unified thought all that the three preceding sentences have placed before us in coordination. So John writes “this One,” re-emphasizing the third sentence, that the Word was God; then “was in the beginning,” re-emphasizing the first sentence, that the Word was in the beginning; finally “with God,” re-emphasizing the second sentence, that the Word was in reciprocal relation with God. Here one of the great characteristics of all inspired writing should not escape us; realities that transcend all human understanding are uttered in words of utmost simplicity yet with flawless perfection. The human mind cannot suggest an improvement either in the terms used or in the combination of the terms that is made. Since John’s first words recall Genesis 1, we point to Moses, the author of that first chapter, as another incomparable example of inspired writing—the same simplicity for expressing transcendent thought, the same perfection in every term and every grammatical combination of terms. Let us study Inspiration from this angle, i.e., from what it has actually produced throughout the Bible. Such study will both increase our faith in Inspiration and give us a better conception of the Spirit’s suggestio rerum et verborum.

3) The first four sentences belong together, being connected, as they are, by two καί and the resumptive οὗτος. They present to us the person of the Logos, eternal and very God. Without a connective v. 3 proceeds with the first work of the Logos, the creation of all things. All things were made through him; and without him was not made a single thing that is made. The negative second half of this statement re-enforces and emphasizes the positive first half. While John advances from the person to the work, this work substantiates what is said about the person; for the Logos who created all things must most certainly be God in essence and in being.

“All things,” πάντα without the article, an immense word in this connection, all things in the absolute sense, the universe with all that it contains. This is more than τὰ πάντα with the article, which would mean all the things that exist at present, while πάντα covers all things present, past, and future. While the preposition διά denotes the medium, Rom. 11:36 and Heb. 2:10 show that the agent himself may be viewed as the medium; hence “through him,” i.e., the Logos, must not be read as though the Logos was a mere tool or instrument. The act of creation, like all the opera ad extra, is ascribed to the three persons of the God-head and thus to the Son as well as to the Father; compare the plural pronouns in Gen. 1:26.

The verb ἐγένετο, both in meaning and in tense, is masterly. The translation of our versions is an accommodation, for the verb means “came into existence,” i.e., “became” in this sense. The existence of all things is due to the Logos, not, indeed, apart from the other persons of the Godhead but in conjunction with them, as is indicated throughout the creative speaking in Gen. 1. “All things came into being” since the beginning, the Logos through whom they were called into being existed before the beginning, from eternity. The verb “became” is written from the point of view of the things that entered existence, while in Genesis the verb “created” is written from the viewpoint of God, the Creator. John repeats ἐγένετο in the negative part of his statement and adds the perfect tense γέγονεν in the attached relative clause. These repetitions emphasize the native meaning of this verb. As creatures of the Logos “all things became.”

The punctiliar tense, a historical aorist, is in marked contrast to the durative imperfect of the four preceding ἦν. This aorist goes back to the creative acts of Gen. 1. These acts are fundamental; for all creatures that came into existence in the later course of time have their origin in the creative acts of that wonderful week recorded in Genesis. We may thus pass down through the centuries, even to the last day of time, and always it will be true: ὁ κόσμος διʼ αὑτοῦ ἐγένετο, “the world was made through him,” v. 10, where this significant verb is repeated for the fourth time.

John’s positive statement is absolute. This the negative counterpart makes certain: and without him was not a single thing made that is made. Whereas the plural πάντα covers the complete multitude or mass, the strong singular οὐδὲ ἕν points to every individual in that mass and omits none. “Not one thing” is negative; hence also the phrase with the verb is negative, “became without him” or apart from him and his creative power. Apart from the Logos is nihil negativum et privativum. Yet in both the positive and the negative statements concerning the existence of all things and of every single thing the implication stands out that the Logos himself is an absolute exception. He never “became” or “came into existence.” No medium (διά) is in any sense connected with his being. The Son is from all eternity “the uncreated Word.”

The relative clause ὃ γέγονεν is without question to be construed with ἕν and cannot be drawn into the next sentence. We need not present all the details involved in this statement since the question must be considered closed. The margin of the R. V., which still offers the other reading, is incorrect and confusing. No man has ever been able to understand the sense of the statement, “That which hath been made was life in him.” Linguistically the perfect tense with its present force, γέγονεν, clashes quite violently with the following imperfect tense ἦν, so violently that the ancient texts were altered, changing οὑδὲ ἕν into οὑδέν, and ζωὴ ἧν into ζωή ἐστιν. But even these textual alterations fail to give satisfaction apart from the grave question of accepting them as the true reading of the text. So we read, “And without him not a single thing that exists came into existence.” The perfect tense γέγονεν, of course, has a present implication and may be translated, “that exists” or “that is made.” But the perfect tense has this force only as including the present result of a past act. The perfect always reaches from the past into the present. The single thing of which John speaks came into existence in the past and only thus is in existence now. What John thus says is that every single thing that now exists traces its existence back to the past moment when it first entered existence. Thus the aorist ἐγένετο is true regarding all things in the universe now or at any time. Every one of them derives its existence from the Logos. Since γέγονεν as a perfect tense includes past origin, we should not press its present force so as to separate the past creative acts of the Logos from the present existence of the creature world.

C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. John’s Gospel (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Publishing House, 1961), 27–38.