You can see my old posts on this (more videos):

You can see my old posts on this (more videos):

Folks, this might be the most important Independence Day to celebrate than ever before. It doesn’t (and never did) mean that you agree with every single thing that America has done. But what this country HAS gotten right is a miraculous achievement, and we are all unfathomably lucky beneficiaries. Have a happy and reflective Fourth!

(Updated 7-3-2021)

I figured this recent “Anthem Protest” would be a good update for the post. This comes to me via RIGHT SCOOP:

Gwen Berry explained today why she reacted with such contempt for the National Anthem over the weekend and it’s absolutely ridiculous (video at Twitter… click pic):

Berry claims that “If you know your history, you know the full song of the National Anthem. The third paragraph speaks to slaves in America, our blood being slang and piltered all over the floor. It’s disrespectful and it does not speak for black Americans. It’s obvious. There’s no question.”

I found this explanation unbelievable. But because I don’t know the verse, I went back and read it anyway:

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

So it turns out she’s an idiot. Yes, it uses the world ‘slave’, but it doesn’t remotely mean what she claims it means. It’s referring to the British, which is clear from the context. Not American slaves.

Erick Erickson provides us more insight here:

[….]

…the third verse of the National Anthem has nothing to do with slave labor. She’s taking language out of context by using a modern day definition and applying it to a 17th century statement. — Kenny Webster

. . . . . .

(Originally Posted Sep 29, 2017)

✩✩✩ OUR NATIONAL ANTHEM ✩✩✩

(Above video description: The original file AND description can be found here in full — HOWEVER, the audio was horrible. I tried to raise the DBs but couldn’t get rid of the hiss… but it is a must watch!)

UPDATED VIDEO ADDED

The Star-Spangled Banner, long a treasured symbol of national unity, has suddenly become “one of the most racist, pro-slavery songs” in American culture. Why is this happening? And more importantly, is it true? USA Today columnist James Robbins explores the history of the song and its author to answer these questions.

A friend asked a question about a challenge via “The Root” about the National Anthem. This is the “verse” said to be “racist”

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

It is said our (yes, OUR) anthem glories in black slaves dying. Here is how it is encapsulated in the NEW YORK TIMES:

The journalist Jon Schwarz, writing in The Intercept, argued yes, denouncing the lyrics, written by Francis Scott Key during the War of 1812, as “a celebration of slavery.” How could black players, Mr. Schwarz asked, be expected to stand for a song whose rarely sung third stanza — which includes the lines “No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave” — “literally celebrates the murder of African-Americans”?

Here is another sport figure’s comments on the flag:

Here, the SMITHSONIAN helps set the scene for us and how the Anthem came to be:

…A week earlier, Francis Scott Key, a 35-year-old American lawyer, had boarded the flagship of the British fleet on the Chesapeake Bay in hopes of persuading the British to release a friend who had recently been arrested. Key’s tactics were successful, but because he and his companions had gained knowledge of the impending attack on Baltimore, the British did not let them go. They allowed the Americans to return to their own vessel but continued guarding them. Under their scrutiny, Key watched on September 13 as the barrage of Fort McHenry began eight miles away.

“It seemed as though mother earth had opened and was vomiting shot and shell in a sheet of fire and brimstone,” Key wrote later. But when darkness arrived, Key saw only red erupting in the night sky. Given the scale of the attack, he was certain the British would win. The hours passed slowly, but in the clearing smoke of “the dawn’s early light” on September 14, he saw the American flag—not the British Union Jack—flying over the fort, announcing an American victory.

Key put his thoughts on paper while still on board the ship, setting his words to the tune of a popular English song. His brother-in-law, commander of a militia at Fort McHenry, read Key’s work and had it distributed under the name “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” The Baltimore Patriot newspaper soon printed it, and within weeks, Key’s poem, now called “The Star-Spangled Banner,” appeared in print across the country, immortalizing his words—and forever naming the flag it celebrated….

THE DAILY CALLER notes (and so does SNOPES) that this verse was in reference to slaves and mercenaries that fought on the British side:

Francis Scott Key wrote the song the morning after the British bombarded Fort McHenry toward the end of the War of 1812, when he saw the American flag still waving. In these lines of the third verse he’s celebrating the death of slaves and mercenaries who opted to fight for the British in exchange for their freedom following the war.

INDEPENDENT JOURNAL REVIEW puts the idea to bullet points:

The U.S. CAPITAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY also comments on the added “fifth verse” by Oliver Wendell Holmes at the start of the Civil War:

Fifty years later, in 1861, poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. would write a fifth verse to the National Anthem, reflecting the nation’s strife and looking toward a more peaceable future:

When our land is illum’d with Liberty’s smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her glory,

Down, down, with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

By the millions unchain’d who our birthright have gained

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the brave.

Here, Wendell, unlike Key, foresaw not only the inevitable emancipation of the nation’s slaves, but also the freed African Americans gaining full citizen rights and ensuring the country’s preservation. Today, this verse is not considered an official part of the National Anthem, but during the Civil War, it was printed in song books throughout the northern United States as an extension of Key’s lyrics. In this way, Francis Scott Key and the War of 1812 bequeathed to the nation not just a song, but a step toward the perpetuating of liberty—just as the Revolutionary War and Civil War did.

Again, the Left views complex history through the lens of a historical Marxist view. Something that Howard Zinn tried to do as well, but did so by rewriting history… as the Modern Left still does.

Francis Scott Key, like many during that time, had a varied history on slavery. He fought for slaves to be free in court – pro bono. But, he also fought to return runaway slaves to owners at some point in his life – probably for money. So he was an opportunistic lawyer to pay bills… nothing has changed. WIKI continues with this:

Key publicly criticized slavery’s cruelties, so much that after his death a newspaper editorial stated “So actively hostile was he to the peculiar institution that he was called ‘The Nigger Lawyer’ …. because he often volunteered to defend the downtrodden sons and daughters of Africa. Mr. Key convinced me that slavery was wrong—radically wrong.” In June 1842, Key attended the funeral of William Costin, a free, mixed race resident who had challenged Washington’s surety bond laws.

The SMITHSONIAN again notes that Key was a founding member and active leader of the American Colonization, of which the primary goal was to send free African-Americans back to Africa. Keys, even though he abhorred slavery, and fought to free slaves at times, was removed from the board in 1833 as its policies shifted toward abolitionist. The mood of the nation as a whole was shifting. While Keys couldn’t envision a multi-ethnic nation, others could. But Keys position wasn’t necessarily “racist,” as some ex-slaves wanted the same. To recall a portion of the above quote from the Capital Historical Society, “…Wendell, unlike Key, foresaw not only the inevitable emancipation of the nation’s slaves, but also the freed African Americans gaining full citizen rights and ensuring the country’s preservation.”

YOU SEE, people change… as do nations (because they, like corporations, are made up of people). I make this point in my post on AUGUSTINE, who is often used to support old-earth positions… but little know that later in his life he rejected the old-earth view and wrote quite a bit on the young earth (creationist) viewpoint.

A man needs to be judged by his life’s journey. As do nations.

Likewise, conservatives believe that Robert Byrd may have sincerely changed his formerly racist beliefs. But when Democrats accuse Republicans of racism because they went to Strom Thurmond’s (one of the only major Dixiecrats to change to Republican – watch here and here) funeral and gave him praise, even though he changed his views on race/racism. All we point out is that if praising an ex Dixiecrat at a funeral makes one racist… then what does lauding a KKK Grand Kleagle at his funeral make Democrats?

A man needs to be judged by his life’s journey.

So does a nation.

Here is the rest of the SMITHSONIAN piece I wish to excerpt:

A religious man, Key believed slavery sinful; he campaigned for suppression of the slave trade. “Where else, except in slavery,” he asked, “was ever such a bed of torture prepared?” Yet the same man, who coined the expression “the land of the free,” was himself an owner of slaves who defended in court slaveholders’ rights to own human property.

Key believed that the best solution was for African-Americans to “return” to Africa—although by then most had been born in the United States. He was a founding member of the American Colonization Society, the organization dedicated to that objective; its efforts led to the creation of an independent Liberia on the west coast of Africa in 1847. Although the society’s efforts were directed at the small percentage of free blacks, Key believed that the great majority of slaves would eventually join the exodus. That assumption, of course, proved to be a delusion. “Ultimately,” says historian Egerton, “the proponents of colonization represent a failure of imagination. They simply cannot envision a multiracial society. The concept of moving people around as a solution was widespread and being applied to Indians as well.”

You see, Americans’ belief then was “not merely in themselves [shocker to millennials] but also in their future…. lying just beyond the western horizon” (ibid). And that is key. As Paul Johnson rightly notes in his history book on America:

“…can a nation rise above the injustices of its origins and, by its moral purpose and performance, atone for them? All nations are born in war, conquest, and crime, usually concealed by the obscurity of a distant past. The United States, from its earliest colonial times, won its title-deeds in the full blaze of recorded history, and the stains on them are there for all to see and censure: the dispossession of a indigenous people, and the securing of self-sufficiency through the sweat and pain of an enslaved race. In the judgmental scales of history, such grievous wrongs must be balanced by the erection of a society dedicated to justice and fairness.”

Paul Johnson, A History of the American People (New York, NY: Harper Perenial, 1997), 3.

Since the death of George Floyd, athletes and activists have been saying that Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling protests were misunderstood and that they were never about the American flag. However, Kaepernick’s reasoning back when he first took a knee in 2016 say otherwise. Join MRCTV’s Nick Kangadis for a new edition of Out Of Left Field where he’ll remind everyone that his protest was, at least in part, about the American flag for Kaepernick. If you’re sick of being talked down to like you don’t understand what’s going on, Kangadis dishes out a little common sense, reason and logic that are typically non-existent when people become too self-righteous about a cause.

I love how all the chatter died down… tears. I wish I knew more of the context behind this:

Larry Elder interviews Anthony Davis on a few topics, I isolate this segment to the kneeling issue.Again, like others, he realizes this is a private business and that a product is being sold. Your petty activism can be done in a better and more constructive way.

Also, I have heard from close family (plural) that no previous rule existed for the players to kneel.

THIS IS NOT THE CASE:

According to the NFL the Game Operations Manual is it’s “Bible”

Here are the NFL’s rules governing the National Anthem, found on pages A 62-63 of the NFL Game Operations Manual (TIME|September 25, 2017). I will emphasize the loophole the players were using and the owners were too scared to make waves because of:

MORE HERE: The 1st Amendment and Colin Kaepernick (September 3rd, 2016)

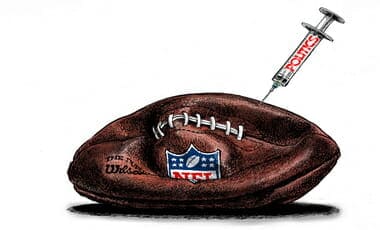

Dennis Prager reads from a TRUTH REVOLT article. What I liked about the article is the empty seat the Viking put in. The NFL is disgraceful… and Prager is right, it is not “national” any longer.

Pamela Dee Gaudry, Georgia physician, took to Facebook on Saturday to criticize Delta Airlines for stopping her from singing the national anthem after her flight landed in Atlanta. According to Gaudry, an announcement was made that the remains of a soldier were onboard the flight and passengers were asked to sit quietly in their seats as the transfer was made. Gaudry then started singing the national anthem to honor the soldier, which is when a flight attendant allegedly told her to stop as it might offend passengers from other countries.

Why should every American stand for the National Anthem? Because the Anthem and the flag represent America, and America is a free nation. That alone is worth standing for. Joy Villa, singer, songwriter, and recording artist, explains.

Historian Paul Johnson Opines:

[p. 3>] The creation of the United States of America is the greatest of all human adventures. No other national story holds such tremendous lessons, for the American people themselves and for the rest of mankind. It now spans four centuries and, as we enter the new millennium, we need to retell it, for if we can learn these lessons and build upon them, the whole of humanity will benefit in the new age which is now opening. American history raises three fundamental questions. First, can a nation rise above the injustices of its origins and, by its moral purpose and performance, atone for them? All nations are born in war, conquest, and crime, usually concealed by the obscurity of a distant past. The United States, from its earliest colonial times, won its title—deeds in the full blaze of recorded history, and the stains on them are there for all to see and censure: the dispossession of an indigenous people, and the securing of self—sufficiency through the sweat and pain of an enslaved race. In the judgmental scales of history, such grievous wrongs must be balanced by the erection of a society dedicated to justice and fairness. Has the United States done this? Has it expiated its organic sins? The second question provides the key to the first. In the process of nation—building, can ideals and altruism—the desire to build the perfect community—be mixed successfully with acquisitiveness and ambition, without which no dynamic society can be built at all? Have the Americans got the mixture right? Have they forged a nation where righteousness has the edge over the needful self—interest? Thirdly, the Americans originally aimed to build another—worldly `City on a Hill,’ but found themselves designing a republic of the people, to be a model for the entire planet. Have they made good their audacious claims? Have they indeed proved exemplars for humanity? And will they continue to be so in the new millennium?

We must never forget that the settlement of what is now the United States was only part of a larger enterprise. And this was the work of the best and the brightest of the entire European continent. They were greedy. As Christopher Columbus said, men crossed the Atlantic primarily in search of gold. But they were also idealists. These adventurous young men thought they could transform the world for the better. Europe was too small for them—for their energies, their ambitions, and [p. 4>] their visions. In the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries, they had gone east, seeking to reChristianize the Holy Land and its surroundings, and also to acquire land there. The mixture of religious zeal, personal ambition—not to say cupidity—and lust for adventure which inspired generations of Crusaders was the prototype for the enterprise of the Americas.

In the east, however, Christian expansion was blocked by the stiffening resistance of the Moslem world, and eventually by the expansive militarism of the Ottoman Turks. Frustrated there, Christian youth spent its ambitious energies at home: in France, in the extermination of heresy, and the acquisition of confiscated property; in the Iberian Peninsula, in the reconquest of territory held by Islam since the 8th century, a process finally completed in the 1490s with the destruction of the Moslem kingdom of Granada, and the expulsion, or forcible conversion, of the last Moors in Spain. It is no coincidence that this decade, which marked the homogenization of western Europe as a Christian entity and unity, also saw the first successful efforts to carry Europe, and Christianity, into the western hemisphere. As one task ended, another was undertaken in earnest.

The Portuguese, a predominantly seagoing people, were the first to begin the new enterprise, early in the 15th century. In 1415, the year the English King Henry V destroyed the French army at Agincourt, Portuguese adventurers took Ceuta, on the north African coast, and turned it into a trading depot. Then they pushed southwest into the Atlantic, occupying in turn Madeira, Cape Verde, and the Azores, turning all of them into colonies of the Portuguese crown. The Portuguese adventurers were excited by these discoveries: they felt, already, that they were bringing into existence a new world, though the phrase itself did not pass into common currency until 1494. These early settlers believed they were beginning civilization afresh: the first boy and girl born on Madeira were christened Adam and Eve. But almost immediately came the Fall, which in time was to envelop the entire Atlantic. In Europe itself, the slave—system of antiquity had been virtually extinguished by the rise of Christian society. In the 1440s, exploring the African coast from their newly acquired islands, the Portuguese rediscovered slavery as a working commercial institution. Slavery had always existed in Africa, where it was operated extensively by local rulers, often with the assistance of Arab traders. Slaves were captives, outsiders, people who had lost tribal status; once enslaved, they became exchangeable commodities, indeed an important form of currency.

[p. 5>] The Portuguese entered the slave—trade in the mid—15th century, took it over and, in the process, transformed it into something more impersonal, and horrible, than it had been either in antiquity or medieval Africa. The new Portuguese colony of Madeira became the center of a sugar industry, which soon made itself the largest supplier for western Europe. The first sugar— mill, worked by slaves, was erected in Madeira in 1452. This cash—industry was so successful that the Portuguese soon began laying out fields for sugar—cane on the Biafran Islands, off the African coast. An island off Cap Blanco in Mauretania became a slave—depot. From there, when the trade was in its infancy, several hundred slaves a year were shipped to Lisbon. As the sugar industry expanded, slaves began to be numbered in thousands: by 1550, some 50,000 African slaves had been imported into Sao Tome alone, which likewise became a slave entrepot. These profitable activities were conducted, under the aegis of the Portuguese crown, by a mixed collection of Christians from all over Europe—Spanish, Normans, and Flemish, as well as Portuguese, and Italians from the Aegean and the Levant. Being energetic, single young males, they mated with whatever women they could find, and sometimes married them. Their mixed progeny, mulattos, proved less susceptible than pure—bred Europeans to yellow fever and malaria, and so flourished. Neither Europeans nor mulattos could live on the African coast itself. But they multiplied in the Cape Verde Islands, 300 miles off the West African coast. The mulatto trading—class in Cape Verde were known as Lancados. Speaking both Creole and the native languages, and practicing Christianity spiced with paganism, they ran the European end of the slave—trade, just as Arabs ran the African end.

This new—style slave—trade was quickly characterized by the scale and intensity with which it was conducted, and by the cash nexus which linked African and Arab suppliers, Portuguese and Lancado traders, and the purchasers. The slave—markets were huge. The slaves were overwhelmingly male, employed in large—scale agriculture and mining. There was little attempt to acculturalize them and they were treated as body—units of varying quality, mere commodities. At Sao Tome in particular this modern pattern of slavery took shape. The Portuguese were soon selling African slaves to the Spanish, who, following the example in Madeira, occupied the Canaries and began to grow cane and mill sugar there too. By the time exploration and colonization spread from the islands across the Atlantic, the slave—system was already in place.

In moving out into the Atlantic islands, the Portuguese discovered [p. 6>] the basic meteorological fact about the North Atlantic, which forms an ocean weather—basin of its own. There were strong currents running clockwise, especially in the summer. These are assisted by northeast trade winds in the south, westerlies in the north. So seafarers went out in a southwest direction, and returned to Europe in a northeasterly one. Using this weather system, the Spanish landed on the Canaries and occupied them. The indigenous Guanches were either sold as slaves in mainland Spain, or converted and turned into farm—labourers by their mainly Castilian conquerors. Profiting from the experience of the Canaries in using the North Atlantic weather system, Christopher Columbus made landfall in the western hemisphere in 1492. His venture was characteristic of the internationalism of the American enterprise. He operated from the Spanish city of Seville but he came from Genoa and he was by nationality a citizen of the Republic of Venice, which then ran an island empire in the Eastern Mediterranean. The finance for his transatlantic expedition was provided by himself and other Genoa merchants in Seville, and topped up by the Spanish Queen Isabella, who had seized quantities of cash when her troops occupied Granada earlier in the year.

The Spanish did not find American colonization easy. The first island—town Columbus founded, which he called Isabella, failed completely. He then ran out of money and the crown took over. The first successful settlement took place in 1502, when Nicolas de Ovando landed in Santo Domingo with thirty ships and no fewer than 2,500 men. This was a deliberate colonizing enterprise, using the experience Spain had acquired in its reconquista, and based on a network of towns copied from the model of New Castile in Spain itself. That in turn had been based on the bastides of medieval France, themselves derived from Roman colony—towns, an improved version of Greek models going back to the beginning of the first millennium BC. So the system was very ancient. The first move, once a beachhead or harbour had been secured, was for an official called the adelantana to pace out the streetgrid.6 Apart from forts, the first substantial building was the church. Clerics, especially from the orders of friars, the Dominicans and Franciscans, played a major part in the colonizing process, and as early as 1512 the first bishopric in the New World was founded. Nine years before, the crown had established a Casa de la Contracion in Seville, as headquarters of the entire transatlantic effort, and considerable state funds were poured into the venture. By 1520 at least 10,000 Spanishspeaking Europeans were living on the island of Hispaniola in the [p. 7>] Caribbean, food was being grown regularly and a definite pattern of trade with Europeans had been established.

The year before, Hernando Cortes had broken into the American mainland by assaulting the ancient civilization of Mexico. The expansion was astonishingly rapid, the fastest in the history of mankind, comparable in speed with and far more exacting in thoroughness and permanency than the conquests of Alexander the Great. In a sense, the new empire of Spain superimposed itself on the old one of the Aztecs rather as Rome had absorbed the Greek colonies.8 Within a few years, the Spaniards were 1,000 miles north of Mexico City, the vast new grid—town which Cortes built on the ruins of the old Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.

This incursion from Europe brought huge changes in the demography, the flora and fauna, and the economics of the Americas. Just as the Europeans were vulnerable to yellow fever, so the indigenous Indians were at the mercy of smallpox, which the Europeans brought with them. Europeans had learned to cope with it over many generations but it remained extraordinarily infectious and to the Indians it almost invariably proved fatal. We do not know with any certainty how many people lived in the Americas before the Europeans came. North of what is now the Mexican border, the Indians were sparse and tribal, still at the hunter—gatherer stage in many cases, and engaged in perpetual inter—tribal warfare, though some tribes grew corn in addition to hunting and lived part of the year in villages—perhaps one million of them, all told. Further south there were far more advanced societies, and two great empires, the Aztecs in Mexico and the Incas in Peru. In central and south America, the total population was about 20 million. Within a few decades, conquest and the disease it brought had reduced the Indians to 2 million, or even less. Hence, very early in the conquest, African slaves were in demand to supply labor. In addition to smallpox, the Europeans imported a host of welcome novelties: wheat and barley, and the ploughs to make it possible to grow them; sugarcanes and vineyards; above all, a variety of livestock. The American Indians had failed to domesticate any fauna except dogs, alpacas and llamas. The Europeans brought in cattle, including oxen for ploughing, horses, mules, donkeys, sheep, pigs and poultry. Almost from the start, horses of high quality, as well as first—class mules and donkeys, were successfully bred in the Americas. The Spanish were the only west Europeans with experience of running large herds of cattle on horseback, and this became an outstanding feature of the New World, where [p. 8>] enormous ranches were soon supplying cattle for food and mules for work in great quantities for the mining districts.

The Spaniards, hearts hardened in the long struggle to expel the Moors, were ruthless in handling the Indians. But they were persistent in the way they set about colonizing vast areas. The English, when they followed them into the New World, noted both characteristics. John Hooker, one Elizabethan commentator, regarded the Spanish as morally inferior `because with all cruel inhumanity … they subdued a naked and yielding people, whom they sought for gain and not for any religion or plantation of a commonwealth, did most cruelly tyrannize and against the course of all human nature did scorch and roast them to death, as by their own histories doth appear.’ At the same time the English admired `the industry, the travails of the Spaniard, their exceeding charge in furnishing so many ships … their continual supplies to further their attempts and their active and undaunted spirits in executing matters of that quality and difficulty, and lastly their constant resolution of plantation.”

With the Spanish established in the Americas, it was inevitable that the Portuguese would follow them. Portugal, vulnerable to invasion by Spain, was careful to keep its overseas relations with its larger neighbor on a strictly legal basis. As early as 1479 Spain and Portugal signed an agreement regulating their respective spheres of trade outside European waters. The papacy, consulted, drew an imaginary longitudinal line running a hundred leagues west of the Azores: west of it was Spanish, east of it Portuguese. The award was made permanent between the two powers by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which drew the lines 370 leagues west of Cape Verde. This gave the Portuguese a gigantic segment of South America, including most of what is now modern Brazil. They knew of this coast at least from 1500 when a Portuguese squadron, on its way to the Indian Ocean, pushed into the Atlantic to avoid headwinds and, to its surprise, struck land which lay east of the treaty line and clearly was not Africa. But their resources were too committed to exploring the African coast and the routes to Asia and the East Indies, where they were already opening posts, to invest in the Americas. Their first colony in Brazil was not planted till 1532, where it was done on the model of their Atlantic island possessions, the crown appointing `captains,’ who invested in land—grants called donatorios. Most of this first wave failed, and it was not until the Portuguese transported the sugar—plantation system, based on slavery, from Cape Verde and the Biafran Islands, to the part of Brazil they called Pernambuco, [p. 9>] that profits were made and settlers dug themselves in. The real development of Brazil on a large scale began only in 1549, when the crown made a large investment, sent over 1,000 colonists and appointed Martin Alfonso de Sousa governor—general with wide powers. Thereafter progress was rapid and irreversible, a massive sugar industry grew up across the Atlantic, and during the last quarter of the 16th century Brazil became the largest slave—importing center in the world, and remained so. Over 300 years, Brazil absorbed more African slaves than anywhere else and became, as it were, an Afro—American territory. Throughout the 16th century the Portuguese had a virtual monopoly of the Atlantic slave trade. By 1600 nearly 300,000 African slaves had been transported by sea to plantations—25,000 to Madeira, 50,000 to Europe, 75,000 to Cape Sao Tome, and the rest to America. By this date, indeed, four out of five slaves were heading for the New World.”

It is important to appreciate that this system of plantation slavery, organized by the Portuguese and patronized by the Spanish for their mines as well as their sugar—fields, had been in place, expanding steadily, long before other European powers got a footing in the New World. But the prodigious fortunes made by the Spanish from mining American silver, and by both Spanish and Portuguese in the sugar trade, attracted adventurers from all over Europe…

Via POLITISTICK:

“One of the biggest things we can do is identify what our problem is. We have a problem which we have a white Marxist organization that has indoctrinated our kids the last 15 years with anti-white, anti-flag, anti-American — everything you see on the sidelines today has been flooded into our community — the liberal filth for 15 years — it’s called Black Entertainment Television [BET].

It’s not owned by black people It’s white people with a black facade, black employees with a message that is anti-American. So you have all these kids growing up in this environment, they’ve become millionaires, they’re going to believe what they were taught to believe.

We are up against a very evil ideology, guys. And understand that and we pull these guys from behind their corporate boardrooms. Have them stand in front of the American people and explain what they are doing to us.”