CHAPTER 4

Economic Systems

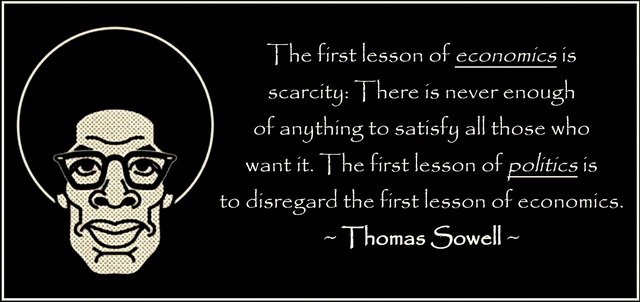

The most fundamental fact of economics, without which there would be no economics, is that what everybody wants always adds up to more than there is. If this were not true, then we would be living in a Garden of Eden, where everything is available in unlimited abundance, instead of in an economy with limited resources and unlimited desires. Because of this inherent scarcity—regardless of whether a particular economic system is one of capitalism, socialism, feudalism, or whatever—an economy not only organizes production and the distribution of the resulting output, it must by its very nature also have ways to prevent people from completely satisfying their desires. That is, it must convey the inherent scarcity, without which there would be no real point to economics, even though the particular kind of economy does not cause that scarcity.

In a market economy, prices convey the inherent scarcity through competing bids for resources and outputs that are inherently inadequate to supply all the bidders with all that they want. This may seem like a small and obvious point, but even such renowned intellectuals as the philosopher John Dewey have grossly misconceived it, blaming the particular economic system that conveys scarcity for causing the scarcity itself. Dewey saw the existing market economy as one “maintaining artificial scarcity” for the sake of “personal profit.”1 George Bernard Shaw likewise saw “restricting output” as the principle on which capitalism was founded.2 Bertrand Russell depicted a market economy as one in which “wealthy highwaymen are allowed to levy toll upon the world for the use of indispensable minerals.”3

According to Dewey, to make “potential abundance an actuality” what was needed was to “modify institutions.”4 But he apparently found it unnecessary to specify any alternative set of economic institutions in the real world which had in fact produced greater abundance than the institutions he blamed for “maintaining artificial scarcity.” As in many other cases, the utter absence of factual evidence or even a single step of logic often passes unnoticed among the intelligentsia, when someone is voicing a view common among their peers and consistent with their general vision of the world.

Similarly, a twenty-first century historian said in passing, as something too obvious to require elaboration, that “capitalism created masses of laborers who were poverty stricken.”5 There were certainly many such laborers in the early years of capitalism, but neither this historian nor most other intellectuals have bothered to show that capitalism created this poverty. If in fact those laborers were more prosperous before capitalism, then not only would such a fact need to be demonstrated, what would also need to be explained is why laborers gave up this earlier and presumably higher standard of living to go work for capitalists for less. Seldom is either of these tasks undertaken by intellectuals who make such assertions—and seldom do their fellow intellectuals challenge them to do so, when they are saying things that fit the prevailing vision.

Social critic Robert Reich has likewise referred in passing to twentieth-century capitalism as producing, among other social consequences, “urban squalor, measly wages and long hours for factory workers”6 but without a speck of evidence that any of these things was better before twentieth-century capitalism. Nothing is easier than simply assuming that things were better before, and nothing is harder than finding evidence of better housing, higher wages and shorter hours in the nineteenth and earlier centuries, whether in industry or agriculture.

The difference between creating a reality and conveying a reality has been crucial in many contexts. The idea of killing the messenger who brings bad news is one of the oldest and simplest examples. But the fundamental principle is still alive and well today, when charges of racial discrimination are made against banks that turn down a higher proportion of black applicants for mortgage loans than of white applicants.

Even when the actual decision-maker who approves or denies loan applications does so on the basis of paperwork provided by others who interview loan applicants face-to-face, and the actual decision-maker has no idea what race any of the applicants are, the decisions made may nevertheless convey differences among racial groups in financial qualifications without being the cause of those differences in qualifications, credit history or the outcomes that result from those differences. The fact that black-owned banks also turn down black applicants at a higher rate than white applicants, and that white-owned banks turn down white applicants at a higher rate than Asian American applicants,7 reinforces the point—but only for those who check out the facts that are seldom mentioned in the media, which is preoccupied with moral melodrama that fits their vision.i Among the many differences among black, white and Asian Americans is that the average credit rating among whites is higher than among blacks and the average credit rating of Asian Americans is higher than among whites.8

In light of the many differences among these three groups, it is hardly surprising that, while blacks were turned down for mortgage loans at twice the rate for whites in 2000, whites were turned down at nearly twice the rate for Asian Americans.9 But only the black-white comparison saw the light of day in much of the media. To have included data comparing mortgage loan denial rates between Asian Americans and whites would have reduced a moral melodrama to a mundane example of elementary economics.

CHAOS VERSUS COMPETITION

Among the other unsubstantiated notions about economics common among the intelligentsia is that there would be chaos in the economy without government planning or control. The order created by a deliberately controlled process may be far easier to conceive or understand than an order emerging from an uncontrolled set of innumerable interactions. But that does not mean that the former is necessarily more common, more consequential or more desirable in its consequences.

Neither chaos nor randomness is implicit in uncontrolled circumstances. In a virgin forest, the flora and fauna are not distributed randomly or chaotically. Vegetation growing on a mountainside differs systematically at different heights. Certain trees grow more abundantly at lower elevations and other kinds of trees at higher elevations. Above some altitude no trees at all grow and, at the summit of Everest, no vegetation at all grows. Obviously, none of this is a result of any decisions made by the vegetation, but depends on variations in surrounding circumstances, such as temperature and soil. It is a systemically determined outcome with a pattern, not chaos.

Animal life also varies with environmental differences and, while animals like humans (and unlike vegetation) have thought and volition, that thought and volition are not always the decisive factors in the outcomes. That fish live in the water and birds in the air, rather than vice versa, is not strictly a matter of their choices, though each has choices of behavior within their respective environments. Moreover, what kinds of choices of behavior will survive the competition that weeds out some kinds of responses to the environment and lets others continue is likewise not wholly a matter of volition. In short, between individual volition and general outcomes are systemic factors which limit or determine what will survive, creating a pattern, rather than chaos.

None of this is difficult to understand in the natural environment. But the difference between individual, volitional causation and constraining systemic causation is one seldom considered by intellectuals when discussing economies, unless they happen to be economists. Yet that distinction has been commonplace among economists for more than two centuries. Nor has this been simply a matter of opinion or ideology. Systemic analysis was as common in Karl Marx’s Capital as in Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, and it existed in the eighteenth century school of French economists called the Physiocrats before either Marx or Smith wrote about economics.

Even the analogy between systemic order in nature and in an economy was suggested by the title of one of the Physiocratic writings of the eighteenth century, L’Ordre Naturel by Mercier de la Rivière. It was the Physiocrats who coined the phrase laissez-faire, later associated with Adam Smith, based on their conviction that an uncontrolled economy was not one of chaos but of order, emerging from systemic interactions among the people competing with, and accommodating to, one another.

Karl Marx, of course, had a less benign view of the pattern of outcomes of market competition than did the Physiocrats or Adam Smith, but what is crucial here is that he too analyzed the market economy in terms of its systemic interactions, rather than its volitional choices, even when these were the choices of its economic elites, such as capitalists. Marx said that “competition” creates economic results that are “wholly independent of the will of the capitalist.”10 Thus, for example, while a new technology with lower production costs enables the capitalist to lower his prices, the spread of that technology to competing capitalists compels him to lower his prices, according to Marx.11

Likewise in his analysis of downturns in the economy— depressions or economic “crises” in Marxian phraseology— Marx made a sharp distinction between systemic causation versus volitional causation:

A man who has produced has not the choice whether he will sell or not. He must sell. And in crises appears precisely the circumstance that he cannot sell, or only below the price of production, or even that he must sell at a positive loss. What does it avail him or us, therefore, that he has produced in order to sell? What concerns us is precisely to discover what has cut across this good intention of his.12

Neither in his theory of economics nor in his theory of history did Marx make end results simply the carrying out of individual volition, even the volition of elites. As his collaborator Friedrich Engels put it, “what each individual wills is obstructed by everyone else, and what emerges is something that no one willed.”13 Economics is about the pattern that emerges. Historian Charles A. Beard could seek to explain the Constitution of the United States by the economic interests of the individuals who wrote it, but that volitional approach was not the approach used by Marx and Engels, despite how often Beard’s theory of history has been confused with the Marxian theory of history. Marx dismissed a similar theory in his own day as “facile anecdote-mongering and the attribution of all great events to petty and mean causes.”14

The question here is not whether most intellectuals agree with systemic analysis, either in economics or elsewhere. Many have never even considered, much less confronted, that kind of analysis. Those who reason in terms of volitional causation see chaos from conflicting individual decisions as the alternative to central control of economic processes. John Dewey, for example, said, “comprehensive plans” are required “if the problem of social organization is to be met.”15 Otherwise, there will be “a continuation of a regime of accident, waste and distress.”16 To Dewey, “dependence upon intelligence” is an alternative to “drift and casual improvisation”17—that is, chaos—and those who are “hostile to intentional social planning” were depicted as being in favor of “atomistic individualism.”18

Here, as in other cases, verbal virtuosity transforms the arguments of people with opposing views into mere emotions. In this case the emotion is hostility to social planning. That hostility is presumably due to the leftover notions of a by-gone era that society can depend on “the unplanned coincidence of the consequences of a vast multitude of efforts put forth by isolated individuals without reference to any social end,” according to Dewey’s characterization of those with whom he disagreed.19 By the time John Dewey said all this—1935—it was more than a century and a half since the Physiocrats first wrote their books, explaining how competitive markets systemically coordinate economic activities and allocate resources through supply and demand adjustments to price movements.

Whether or not one agrees with the Physiocrats’ explanations, or the similar and more sophisticated explanations of later economists, these are the arguments that would have to be answered if such arguments were not so widely evaded by reducing them to emotions or by using other arguments without arguments. Professor Ronald Dworkin of Oxford, for example, simply dismissed arguments for systemic causation in general, whether in the economy or elsewhere, as “the silly faith that ethics as well as economics moves by an invisible hand, so that individual rights and the general good will coalesce, and law based on principle will move the nation to a frictionless utopia where everyone is better off than he was before.”20

Here again, verbal virtuosity transforms an opposing argument, rather than answering it with either logic or evidence. Moreover, as of the time when Professor Dworkin made this claim, there were numerous examples of countries whose economies were primarily market economies and others whose economies clearly were not, so that empirical comparisons were readily available, including comparisons of countries composed of the same peoples—East Germany versus West Germany or North Korea versus South Korea, for example. But verbal virtuosity made both analytical and empirical arguments unnecessary.

Economic competition is what forces innumerable disparate individual decisions to be reconciled with one another, as transactions terms are forced to change in response to changes in supply and demand, which in turn change economic activities. This is not a matter of “faith” (as Dworkin would have it) or of ideology (as Dewey would have it), but of economic literacy. John Dewey could depict businesses as controlling markets but that position is not inherent in being ideologically on the left. Karl Marx was certainly on the left, but the difference was that he had studied economics, as deeply as anyone of his time.

Just as Karl Marx did not attribute what he saw as the detrimental effects of a market economy to the ill will of individual capitalists, so Adam Smith did not attribute what he saw as the beneficial effects of a market economy to the good will of individual capitalists. Smith’s depictions of businessmen were at least as negative as those of Marx,21 even though Smith is rightly regarded as the patron saint of free market economics. According to Smith, the beneficial social effects of the businessman’s endeavors are “no part of his intention.”22 Both in Adam Smith’s day and today, more than two centuries later, arguments for a free market economy are based on the systemic effects of such economies in allocating scarce resources which have alternative uses through competition in the marketplace. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the conclusions, this is the argument that must be confronted—or evaded.

Contrary to Dewey and many others, systemic arguments are independent of any notions of “atomistic individualism.” These are not arguments that each individual’s well-being adds up to the well-being of society. Such an argument would ignore the systemic interactions which are at the heart of economic analysis, whether by Adam Smith, Karl Marx or other economists. These economic arguments need not be elaborated here, since they are spelled out at length in economics textbooks.23 What is relevant here is that those intellectuals who see chaos as the alternative to government planning or control have seldom bothered to confront those arguments and have instead misconceived the issue and distorted the arguments of those with different views.

Despite the often expressed dichotomy between chaos and planning, what is called “planning” is the forcible suppression of millions of people’s plans by a government-imposed plan. What is considered to be chaos are systemic interactions whose nature, logic and consequences are seldom examined by those who simply assume that “planning” by surrogate decision-makers must be better. Herbert Croly, the first editor of the New Republic and a major intellectual figure in the Progressive era, characterized Thomas Jefferson’s conception of limited government as “the old fatal policy of drift,” as contrasted with Alexander Hamilton’s policy of “energetic and intelligent assertion of the national good.” According to Croly, what was needed was “an energetic and clear-sighted central government.”24 In this conception, progress depends on surrogate decision-makers, rather than on millions of others making their own decisions and exerting their own efforts.

Despite the notion that scarcity is contrived for the sake of profit in a market economy, that scarcity is at the heart of any economy—capitalist, socialist, feudal or whatever. Given that this scarcity is inherent in the system as a whole—any economic system—this scarcity must be conveyed to each individual in some way. In other words, it makes no sense for any economy to produce as much as physically possible of any given product, because that would have to be done with scarce resources which could be used to produce other products, whose supply is also inherently limited to less than what people want.

Markets in capitalist economies reconcile these competing demands for the same resources through price movements in both the markets for consumer goods and the market for the resources which go into producing those consumer goods. These prices make it unprofitable for one producer to use a resource beyond the point where that resource has a greater value to some competing producer who is bidding for that same resource, whether for making the same product or a different product.

For the individual manufacturer, the point at which it would no longer be profitable to use more of some factor of production—machinery, labor, land, etc.—is indeed the point which provides the limit of that manufacturer’s output, even when it would be physically possible to produce more. But, while profitability and unprofitability convey that limit, they are not what cause that limit—which is due to the scarcity of resources inherent in any economic system, whether or not it is a profit-based system. Producing more of a given output in disregard of those limits does not make an economy more prosperous. On the contrary, it means producing an excess of one output at the cost of a shortage of another output that could have been produced with the same resources. This was a painfully common situation in the government-run economy of the Soviet Union, where unsold goods often piled up in warehouses while dire shortages had people waiting in long lines for other goods.25

Ironically, Marx and Engels had foreseen the economic consequences of fiat prices created by government, rather than by supply and demand, long before the founding of the Soviet Union, even though the Soviets claimed to be following Marxian principles. When publishing a later edition of Marx’s 1847 book, The Poverty of Philosophy, in which Marx rejected fiat pricing, Engels spelled out the problem in his editor’s introduction. He pointed out that it is price fluctuations which have “forcibly brought home to the individual commodity producers what things and what quantity of them society requires or does not require.” Without such a mechanism, he demanded to know “what guarantee we have that necessary quantity and not more of each product will be produced, that we shall not go hungry in regard to corn and meat while we are choked in beet sugar and drowned in potato spirit, that we shall not lack trousers to cover our nakedness while trouser buttons flood us in millions.”26

On this point, the difference between Marx and Engels, on the one hand, and many other intellectuals of the left on the other, was simply that Marx and Engels had studied economics and the others usually had not. John Dewey, for example, demanded that “production for profit be subordinated to production for use.”27 Since nothing can be sold for a profit unless some buyer has a use for it, what Dewey’s proposition amounts to is that third-party surrogates would define which use must be subordinated to which other use, instead of having such results be determined systemically by millions of individuals making their own mutual accommodations in market transactions.

As in so many other situations, the most important decision is who makes the decision. The abstract dichotomy between “profit” and “use” conceals the real conflict between millions of people making decisions for themselves and having anointed surrogates taking those decisions out of their hands.

A volitional view of economics enables the intelligentsia, like politicians and others, to dramatize economics, explaining high prices by “greed”j and low wages by a lack of “compassion,” for example. While this is part of an ideological vision, an ideology of the left is not sufficient by itself to explain this approach. “I paint the capitalist and the landlord in no sense couleur de rose,” Karl Marx said in the introduction to the first volume of Capital. “My stand-point,” he added, however, “can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.”28 In short, prices and wages were not determined volitionally but systemically.

Understanding that was not a question of being on the left or not, but of being economically literate or illiterate. The underlying notion of volitional pricing has, in our own times, led to at least a dozen federal investigations of American oil companies over the years, in response to either gasoline shortages or increases in gasoline prices—with none of these investigations turning up facts to support the sinister explanations abounding in the media and in politics when these investigations were launched. Many people find it hard to believe that negative economic events are not a result of villainy, even though they accept positive economic events— the declining prices of computers that are far better than earlier computers, for example—as being just a result of “progress” that happens somehow.

In a market economy, prices convey an underlying reality about supply and demand—and about production costs behind supply, as well as innumerable individual preferences and trade-offs behind demand. By regarding prices as merely arbitrary social constructs, some can imagine that existing prices can be replaced by prices controlled by government, reflecting wiser and nobler notions, such as “affordable housing” or “reasonable” health care costs. A history of price controls going back for centuries, in countries around the world, shows negative and even disastrous consequences from treating prices as mere arbitrary constructs, rather than as symptoms and conveyances of an underlying reality that is not nearly as susceptible of control as the prices are.

As far as many, if not most, intellectuals are concerned, history would show that but does not, because they often see no need to consult history or any other validation process beyond the peer consensus of other similarly disposed intellectuals when discussing economic issues.

The crucial distinction between market transactions and collective decision-making is that in the market people are rewarded according to the value of their goods and services to those particular individuals who receive those goods and services, and who have every incentive to seek alternative sources, so as to minimize their costs, just as sellers of goods and services have every incentive to seek the highest bids for what they have to offer. But collective decision-making by third parties allows those third parties to superimpose their preferences on others at no cost to themselves, and to become the arbiters of other people’s economic fate without accountability for the consequences.

Nothing better illustrates the difference between a volitional explanation of economic activity and a systemic explanation than the use of “greed” as an explanation of high incomes. Greed may well explain an individual’s desire for more money, but income is determined by what other people pay, whether those other people are employers or consumers. Except for criminals, most people in a market economy receive income as a result of voluntary transactions. How much income someone receives voluntarily depends on other people’s willingness to part with their money in exchange for what the recipient offers, whether that is labor, a commodity or a service. John D. Rockefeller did not become rich simply because he wanted money; he became rich because other people preferred to buy his oil, for example, because it was cheaper. Bill Gates became rich because people around the world preferred to buy his computer operating system rather than other operating systems that were available.

None of this is rocket science, nor is it new. A very old expression captured the fallacy of volitional explanations when it said, “If wishes were horses, beggars would ride.” Yet volitional explanations of prices and incomes continue to flourish among the intelligentsia. Professor Peter Corning of Stanford University, for example, attributes high incomes to personality traits found supposedly in one-third of the population because “the ‘free market’ capitalist system favors the one-third who are the most acquisitive and egocentric and the least concerned about fairness and justice.”29 This description would apply as readily to petty criminals who rob local stores and sometimes shoot their owners to avoid being identified, often for small sums of money that would never support the lifestyle of the rich and famous. The volitional explanation of high incomes lacks even correlation, much less causation.

The tactical advantage of volitional explanations is not only that it allows the intelligentsia to be on the side of the angels against the forces of evil, but also that it avoids having to deal with the creation of wealth, an analysis of which could undermine their whole social vision. By focusing on the money that John D. Rockefeller received, rather than the benefits that millions of other people received from Rockefeller—which provided the reason for turning their money over to him in the first place, rather than buying from somebody else—such transactions can be viewed as moral melodramas, rather than mundane transactions for mutual advantage. Contrary to “robber baron” rhetoric, Rockefeller did not reduce the wealth of society but added to it, his own fortune being a share in that additional wealth, as his production efficiencies and innovations reduced the public’s cost of oil to a fraction of what it had been before.

ZERO-SUM ECONOMICS

Among the consequences of the economic illiteracy of most intellectuals is the zero-sum vision of the economy mentioned earlier, in which the gains of one individual or one group represent a corresponding loss to another individual or another group. According to noted twentieth-century British scholar Harold Laski, “the interests of capital and labor are irreconcilable in fundamentals—there’s a sum to divide and each wants more than the other will give.”30 This assumption is seldom spelled out this plainly, perhaps not even in the minds of most of those whose conclusions require such an implicit zero-sum assumption as a foundation. But the widespread notion, coalescing into a doctrine, that one must “take sides” in making public policy or even in rendering judicial decisions, ignores the fact that economic transactions would not continue to take place unless both sides find these transactions preferable to not making such transactions.

Contrary to Laski and many others with similar views, there is no given “sum to divide,” as there would be with manna from heaven. It is precisely the cooperation of capital and labor which creates a wealth that would not exist otherwise, and that both sides would forfeit if they did not reconcile their conflicting desires at the outset, in order to agree on terms under which they can join together to produce that output. It is literally preposterous (putting in front what comes behind) to begin the analysis with “a sum to divide”—that is, wealth—when that wealth can be created only after capital and labor have already reconciled their competing claims and agreed to terms on which they can operate together to produce that wealth.

Each side would of course prefer to have the terms favor themselves more, but both sides must be willing to accept some mutually agreeable terms or no such transaction will take place at all, much less continue. Far from being an “irreconcilable” situation, as Laski claimed, it is a situation reconciled millions of times each day. Otherwise, the economy could not function. Indeed, a whole society could not function without vast numbers of both economic and non-economic decisions to cooperate, despite the fact that no two sets of interests, even among members of the same family, are exactly the same. The habit of many intellectuals to largely ignore the prerequisites, incentives and constraints involved in the production of wealth has many ramifications that can lead to many fallacious conclusions, even if their verbal virtuosity conceals those fallacies from others and from themselves.

Intervention by politicians, judges, or others, in order to impose terms more favorable to one side—minimum wage laws or rent control laws, for example—reduces the overlapping set of mutually agreeable terms and, almost invariably, reduces the number of mutually acceptable transactions, as the party disfavored by the intervention makes fewer transactions subsequently. Countries with generous minimum wage laws, for example, often have higher unemployment rates and longer periods of unemployment than other countries, as employers offer fewer jobs to inexperienced and low-skilled workers, who are typically the least valued and lowest paid—and who are most often priced out of a job by minimum wage laws.

It is not uncommon in European countries with generous minimum wage laws, as well as other worker benefits that employers are mandated to pay for, to have inexperienced younger workers with unemployment rates of 20 percent or more.31 Employers are made slightly worse off by having to rearrange their businesses and perhaps pay for more machinery to replace the low-skilled workers whom it is no longer economic to hire. But those low-skilled, usually younger, workers may be made much worse off by not being able to get jobs as readily, losing both the wages they could earn otherwise and sustaining the perhaps greater loss of not acquiring the work experience that would lead to better jobs and higher pay.

In short, “taking sides” often ends up making both sides worse off, even if in different ways and to different degrees. But the very idea of taking sides is based on treating economic transactions as if they were zero-sum events. This zero-sum vision of the world is also consistent with the disinterest of many intellectuals in what promotes or impedes the creation of wealth, on which the standard of living of a whole society depends, even though the creation of more wealth has lifted “the poor” in the United States today to economic levels not reached by most of the American population in past eras or in many other countries even today.

Just as minimum wage laws tend to reduce employment transactions with those whose pay is most affected, so rent control laws have been followed by housing shortages in Cairo, Melbourne, Hanoi, Paris, New York and numerous other places around the world. Here again, attempts to make transactions terms better for one party usually lead the other party to make fewer transactions. Builders especially react to rent control laws by building fewer apartment buildings and, in some places, building none at all for years on end.

Landlords may continue to rent existing apartments but often they cut back on ancillary services such as painting, repairs, heat and hot water—all of which cost money and all of which are less necessary to maintain at previous levels to attract and keep tenants, once there is a housing shortage. The net result is that apartment buildings that receive less maintenance deteriorate faster and wear out, without adequate numbers of replacements being built. In Cairo, for example, this process led to families having to double up in quarters designed for only one family. The ultimate irony is that such laws can also lead to higher rents on average— New York and San Francisco being classic examples—when luxury housing is exempted from rent control, causing resources to be diverted to building precisely that kind of housing.

The net result is that tenants, landlords, and builders can all end up worse off than before, though in different ways and to different degrees. Landlords seldom end up living in crowded quarters or on the street, and builders can simply devote more of their time and resources to building other structures such as warehouses, shopping malls and office buildings, as well as luxury housing, all of which are usually not subject to rent control laws. But, again, the crucial point is that both sides can end up worse off as a result of laws and policies based on “taking sides,” as if economic transactions were zero-sum processes.

One of the few writers who has explicitly proclaimed the zero-sum vision of the economy—Professor Lester C. Thurow of M.I.T., author of The Zero-Sum Society—has also stated that the United States has been “consistently the industrial economy with the worst record” on unemployment. He spelled it out:

Lack of jobs has been endemic in peacetime during the past fifty years of American history. Review the evidence: a depression from 1929 to 1940, a war from 1941 to 1945, a recession in 1949, a war from 1950 to 1953, recessions in 1954, 1957–58, and 1960–61, a war from 1965 to 1973, a recession in 1969–70, a severe recession in 1974–75, and another recession probable in 1980. This is hardly an enviable economic performance.32

Several things are remarkable about Professor Thurow’s statement. He reaches sweeping conclusions about the record of the United States vis-à-vis the record of other industrial nations, based solely on a recitation of events within the United States—a one-nation international comparison when it comes to facts, rather than rhetoric. Studies which in fact compare the unemployment rate in the United States versus Western European nations, for example, almost invariably show Western European nations with higher unemployment rates, and longer periods of unemployment, than the United States.33 Moreover, the wars that Professor Thurow throws in, in what is supposed to be a discussion of unemployment, might leave the impression that wars contribute to unemployment, when in fact unemployment virtually disappeared in the United States during World War II and has been lower than usual during the other wars mentioned.34

Professor Thurow’s prediction about a recession in 1980 turned out to be true, though that was hardly a daring prediction in the wake of the “stagflation” of the late 1970s. What turned out to be false was the idea that large-scale government intervention was required to head off more unemployment—that, in Thurow’s words, the government needed to “restructure the economy so that it will, in fact, provide jobs for everyone.”35 What actually happened was that the Reagan administration took office in 1981 and did the exact opposite of what Lester Thurow advocated—and, after the recession passed, there were twenty years of economic growth, low unemployment and low inflation.36

Professor Thurow was not, and is not, some fringe kook. According to the material on the cover of the 2001 reprint of his 1980 book The Zero-Sum Society, “Lester Thurow has been professor of management and economics at MIT for more than thirty years.” He is also the “author of several books, including three New York Times best sellers, he has served on the editorial board of the New York Times, as a contributing editor of Newsweek, and as a member of Time magazine’s Board of Economics.” He could not be more mainstream—or more wrong. But what he said apparently found resonance among the elite intelligentsia, who made him an influence on major media outlets.

Similar prescriptions for active government intervention in the economy have abounded among intellectuals, past and present. John Dewey, for example, used such attractive phrases as “socially organized intelligence in the conduct of public affairs,”37 and “organized social reconstruction”38 as euphemisms for the plain fact that third-party surrogate decision-makers seek to have their preferences imposed on millions of other people through the power of government. Although government is often called “society” by those who advocate this approach, what is called “social” planning are in fact government orders over-riding the plans and mutual accommodations of millions of people subject to those orders.

Despite whatever vision may be conjured up by euphemisms, government is not some abstract embodiment of public opinion or Rousseau’s “general will.” Government consists of politicians, bureaucrats, and judges—all of whom have their own incentives and constraints, and none of whom can be presumed to be any less interested in the promotion of their own interests or notions than are people who buy and sell in the marketplace. Neither sainthood nor infallibility is common in either venue. The fundamental difference between decision-makers in the market and decision-makers in government is that the former are subject to continuous and consequential feedback which can force them to adjust to what others prefer and are willing to pay for, while those who make decisions in the political arena face no such inescapable feedback to force them to adjust to the reality of other people’s desires and preferences.

A business with red ink on the bottom line knows that this cannot continue indefinitely, and that they have no choice but to change whatever they are doing that produces red ink, for which there is little tolerance even in the short run, and which will be fatal to the whole enterprise in the long run. In short, financial losses are not merely informational feedback but consequential feedback which cannot be ignored, dismissed or spun rhetorically through verbal virtuosity.

In the political arena, however, only the most immediate and most attention-getting disasters—so obvious and unmistakable to the voting public that there is no problem of “connecting the dots”—are comparably consequential for political decision-makers. But laws and policies whose consequences take time to unfold are by no means as consequential for those who created those laws and policies, especially if the consequences emerge after the next election. Moreover, there are few things in politics as unmistakable in its implications as red ink on the bottom line is in business. In politics, no matter how disastrous a policy may turn out to be, if the causes of the disaster are not understood by the voting public, those officials responsible for the disaster may escape any accountability, and of course they have every incentive to deny having made mistakes, since admitting mistakes can jeopardize a whole career.

Why the transfer of economic decisions from the individuals and organizations directly involved—often depicted collectively and impersonally as “the market”—to third parties who pay no price for being wrong should be expected to produce better results for society at large is a question seldom asked, much less answered. Partly this is because of rhetorical packaging by those with verbal virtuosity. To say, as John Dewey did, that there must be “social control of economic forces”39 sounds good in a vague sort of way, until that is translated into specifics as the holders of political power forbidding voluntary transactions among the citizenry.

FOOTNOTES

1 John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 2000), p. 43.

2 Bernard Shaw, The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (New York: Brentano’s Publishers, 1928), p. 208.

3 Bertrand Russell, Sceptical Essays (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1928), p. 230.

4 John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action, p. 65.

5 Aida D. Donald, Lion in the White House: A Life of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Basic Books, 2007), p. 10.

6 Robert B. Reich, Supercapitalism: The Transformation of Business, Democracy, and Everyday Life (New York: Vintage Books, 2008), p. 21.

7 Harold A. Black, et al., “Do Black-Owned Banks Discriminate against Black Borrowers?” Journal of Financial Ser vices Research, February 1997, pp. 185– 200.

8 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to the Congress on Credit Scoring and Its Effects on the Availability and Affordability of Credit, submitted to the Congress pursuant to Section 215 of the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of 2003, August 2007, p. 80.

9 United States Commission on Civil Rights, Civil Rights and the Mortgage Crisis (Washington: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 2009), p. 53.

10 Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1909), Vol. III, pp. 310– 311.

11 Karl Marx, “Wage Labour and Capital,” section V, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Selected Works (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1955), Vol. I, p. 99. See also Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. III, pp. 310–311.

12 Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value: Selections (New York: International Publishers, 1952), p. 380.

13 Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Selected Correspondence 1846–1895, translated by Dona Torr (New York: International Publishers, 1942), p. 476.

14 Ibid., p. 159.

15 John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action, p. 73. “Unless freedom of individual action has intelligence and informed conviction back of it, its manifestation is almost sure to result in confusion and disorder.” John Dewey, Intelligence in the Modern World: John Dewey’s Philosophy, edited by Joseph Ratner (New York: Modern Library, 1939), p. 404.

16 John Dewey, Human Nature and Conduct: An Introduction to Social Psychology (New York: Modern Library, 1957), p. 277.

17 John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action, p. 56.

18 Ibid., p. 50.

19 Ibid., p. 65.

20 Ronald Dworkin, Taking Rights Seriously (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980), p. 147.

21 Adam Smith denounced “the mean rapacity, the monopolizing spirit of merchants and manufacturers” and “the clamour and sophistry of merchants and manufacturers,” whom he characterized as people who “seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public.” As for policies recommended by such people, Smith said: “The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (New York: Modern Library, 1937), pp. 128, 250, 460. Karl Marx wrote, in the preface to the first volume of Capital: “I paint the capitalist and the landlord in no sense couleur de rose. But here individuals are dealt with only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, embodiments of particular class-relations and class-interests. My standpoint, from which the evolution of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.” In Chapter X, Marx made dire predictions about the fate of workers, but not as a result of subjective moral deficiencies of the capitalist, for Marx said: “As capitalist, he is only capital personified” and “all this does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist.” Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1919), Vol. I, pp. 15, 257, 297.

22 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 423.

23 My own sketch of these arguments can be found in Chapters 2 and 4 of my Basic Economics: A Common Sense Guide to the Economy, fourth edition (New York: Basic Books, 2011). More elaborate and more technical accounts can be found in more advanced texts.

24 Herbert Croly, The Promise of American Life (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989), pp. 44, 45.

25 See, for example, Nikolai Shmelev and Vladimir Popov, The Turning Point: Revitalizing the Soviet Economy (New York: Doubleday, 1989), pp. 141, 170; Midge Decter, An Old Wife’s Tale: My Seven Decades in Love and War (New York: Regan Books, 2001), p. 169.

26 Frederick Engels, “Introduction to the First German Edition,” Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (New York: International Publishers, 1963), p. 19.

27 John Dewey, Characters and Events: Popular Essays in Social and Political Philosophy, edited by Joseph Ratner (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1929), Vol. II, p. 555.

28 Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. I, p. 15.

29 Peter Corning, The Fair Society: The Science of Human Nature and the Pursuit of Social Justice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), p. 125.

30 Harold J. Laski, Letter to Oliver Wendell Holmes, September 13, 1916, Holmes-Laski Letters: The Correspondence of Mr. Justice Holmes and Harold J. Laski 1916–1935, edited by Mark DeWolfe Howe (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1953), Vol. I, p. 20.

31 Holman W. Jenkins, Jr., “Business World: Shall We Eat Our Young?” Wall Street Journal, January 19, 2005, p. A13.

32 Lester C. Thurow, The Zero-Sum Society: Distribution and the Possibilities for Economic Change (New York: Basic Books, 2001), p. 203.

33 Beniamino Moro, “The Economists’ ‘Manifesto’ On Unemployment in the EU Seven Years Later: Which Suggestions Still Hold?” Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review, June-September 2005, pp. 49–66; Economic Report of the President (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2009), pp. 326–327.

34 Theodore Caplow, Louis Hicks and Ben J. Wattenberg, The First Measured Century: An Illustrated Guide to Trends in America, 1900–2000 (Washington: AEI Press, 2001), p. 47.

35 Lester C. Thurow, The Zero-Sum Society, p. 203.

36 “The Turning Point,” The Economist, September 22, 2007, p. 35.

37 John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action, p. 53. See also p. 88.

38 Ibid., p. 89.

39 Ibid., p. 44.

The Matildas were missing several established internationals on Wednesday night, including star striker Kyah Simon. They also rotated players more than usual, which contributed to a lack of cohesion. However, there is no denying losing to a team of school boys is far from ideal preparation for the world’s fifth ranked team in their quest for Olympic gold at Rio. The following is with a H/T to

The Matildas were missing several established internationals on Wednesday night, including star striker Kyah Simon. They also rotated players more than usual, which contributed to a lack of cohesion. However, there is no denying losing to a team of school boys is far from ideal preparation for the world’s fifth ranked team in their quest for Olympic gold at Rio. The following is with a H/T to