Nearly every American knows the phrase “separation of church and state.” Do you know where it’s from? Here’s a hint: it’s not in the Constitution. John Eastman, professor of law at Chapman University, explains how and why this famous phrase has played such an outsized role in American life and law.

An excerpt from a larger paper (the below was originally posted Jul 26, 2015):

…The First Amendment never intended to separate Christian principles from government. Yet today we so often hear the First Amendment coupled with the phrase “separation of church and state. The First Amendment simply states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Obviously, the words “separation,” “church,” or “state” are not found in the First Amendment; furthermore, that phrase appears in no founding document! While most recognize the phrase “separation of church and state,” few know its source; but it is important to understand the origins of that phrase. What is the history of the First Amendment?

The process of drafting the First Amendment made the intent of the Founders abundantly clear; for before they approved the final wording, the First Amendment went through nearly a dozen different iterations and extensive discussions.

Those discussions – recorded in the Congressional Records from June 7 through September 25, 1789 – make clear their intent for the First Amendment. For example, the original version (followed by later versions) introduced in the Senate on September 3, 1789, stated:

- “Congress shall not make any law establishing any religious denomination.”

- “Congress shall make no law establishing any particular denomination.”

- “Congress shall make no law establishing any particular denomination in preference to another.”

- “Congress shall make no law establishing religion [denomination] or prohibiting the free exercise there of.”

By it, the Founders were saying: “We do not want in America what we had in Great Britain: we don’t want one denomination running the nation. We will not have Catholics, or Anglicans, or any other single denomination. We do want God’s principles, but we don’t want one denomination running the nation.”

Of interest is the proposal that George Mason – a member of the Constitutional Convention and “The Father of the Bill of Rights” – put forth for the First Amendment:

- “All men have equal, natural and unalienable right to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that no particular sect or society of Christians [denomination] ought to be favored or established by law in preference to others.”

Their intent was well understood, as evidence by court rulings after the First Amendment. For example, a 1799 court declared:

- “By our form of government, the Christian principles – we do want God’s principles – but we don’t want one denomination to run the nation.”

Again, note the emphasis: “We do want Christian principles – we do want God’s principles – but we don’t want one denomination to run the nation.”

[….]

On the day the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence, they underwent an immediate transformation. The day before, each of them had been a British citizen, living in a British colony, with thirteen crown-appointed British state governments. However, when they signed that document and separated from Greta Britain, they lost all of their State governments.

Consequently, they returned home from Philadelphia to their own States and began to create new State constitutions. Samuel Adams and John Adams helped write the Massachusetts constitution; Benjamin Rush and James Wilson helped write Pennsylvania’s constitution; George Read and Thomas McKean helped write Delaware’s constitution; the same is true in other States as well. The Supreme Court in Church of Holy Trinity v. United States (1892) pointed to these State constitutions as precedents to demonstrate the Founders’ intent.

Notice, for example, what Thomas McKean and George Read placed in the Delaware constitution:

- “Every person, who shall be chosen a member of either house, or appointed to any office or place of trust… shall… make and subscribe the following declaration, to wit: ‘I do profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God, blessed forever more, and I acknowledge the Holy Scripture of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration.’”

Take note of some other State constitutions. The Pennsylvania constitution authored by Benjamin Rush and James Wilson declared:

- “And each member [of the legislature], before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz: ‘I do believe in one God, the Creator and Governor of the Universe, the rewarded of the good and the punisher of the wicked, and I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine Inspiration.’”

The Massachusetts constitution, authored by Samuel Adams – the Father of the American Revolution – and John Adams, stated:

- “All persons elected must make and subscribe the following declaration, viz. ‘I do declare that I believe the Christian religion and have firm persuasions of its truth.’”

North Carolina’s constitution required that:

- “No person, who shall deny the being of God, or the truth of the [Christian] religion, or the Divine authority either of the Old or New Testaments, or who shall hold religious principles incompatible with the freedom and safety of the State, shall be capable of holding any office, or place of trust or profit in the civil department, within this State.”

You had to apply God’s principles to public service, otherwise you were not allowed to be a part of the civil government. In 1892, the Supreme Court (Church of Holy Trinity v. United States) pointed out that of the forty-four States that were then in the Union, each had some type of God-centered declaration in its constitution. Not just any God, or a general God, say a “higher power,” but thee Christian God as understood in the Judeo-Christian principles and Scriptures. This same Supreme Court was driven to explain the following:

- “This is a religious people. This is historically true. From the discovery of this continent to the present hour, there is a single voice making this affirmation…. These are not individual sayings, declarations of private persons: they are organic utterances; they speak the voice of the entire people…. These and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.”

- See as well: Separation of Church & State: What the Founders Meant, by David Barton

JOHN ADAMS

- “…we have no government, armed with power, capable of contending with human passions, unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge and licentiousness would break the strongest cords of our Constitution, as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

John Adams, first (1789–1797) Vice President of the United States, and the second (1797–1801) President of the United States. Letter to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts, 11 October 1798, in Revolutionary Services and Civil Life of General William Hull (New York, 1848), pp 265-6. (PDF found here)

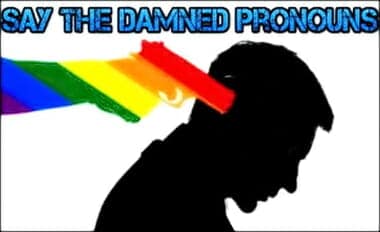

The Left Rejects Separation of Church and State

(July 7, 2016)

GAY PATRIOT notes that at one time the left wanted a strict separation of church and state. Now they wish to regulate it! In the NATIONAL REVIEW article GP links to, we read:

I’m old enough to remember when Christians who expressed concern that LGBT activists would attempt to regulate church services were dismissed as paranoid nutjobs. Well, welcome to our new paranoid future. My friends and colleagues at the Alliance Defending Freedom announced today that they were filing suit against the Iowa Civil Rights Commission to block enforcement of gender identity guidelines that purport to regulate “a church service open to the public.” News flash — virtually every church service is open to the public.

[….]

Incredibly, the document contains an FAQ specifically directed at churches. Here it is:

DOES THIS LAW APPLY TO CHURCHES?

Sometimes. Iowa law provides that these protections do not apply to religious institutions with respect to any religion-based qualifications when such qualifications are related to a bona fide religious purpose. Where qualifications are not related to a bona fide religious purpose, churches are still subject to the law’s provisions. (e.g. a child care facility operated at a church or a church service open to the public).

It’s unclear to me how a branch of the Iowa state government has determined that a “church service open to the public” does not have a “bona fide religious purpose,” but there it is. Under current guidance, churches in Iowa must become “members only” to exercise their religious liberty. It’s tough to imagine this guidance surviving even liberal judicial review, but even if struck down it shows where some on the Left want to take the law. Not even the sanctuary is safe.