This was to be the first of many times that an American president would plot to overthrow a foreign government–a dangerous game but one that the Jefferson administration found as hard to pass up as many of its successors would. Wrote Madison:

“Although it does not accord with the general sentiments or views of the United States to intermiddle in the domestic contests of other countries, it cannot be unfair, in the prosecution of a just war, or the accomplishment of a reasonable peace, to turn to their advantage, the enmity and pretensions of others against a common foe.”

Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2002), 23-24.

This audio is with a h/t to The Religion of Conquest:

America’s first foreign war: lessons learned from fighting muslim pirates, by Michael Medved:

Most Americans remain utterly ignorant of this nation’s first foreign war but that exotic, long-ago struggle set the pattern for nearly all the many distant conflicts that followed. Refusal to confront the lessons of the First Barbary War (1801-1805) has led to some of the silliest arguments concerning Iraq and Afghanistan, and any effort to apply traditional American values to our future foreign policy requires an understanding of this all-but-forgotten episode from our past.

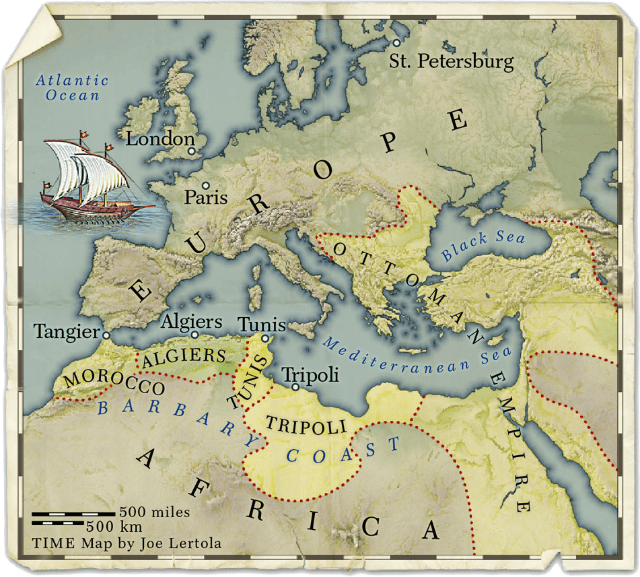

The war against the Barbary States of North Africa (Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli—today’s Libya) involved commitment and sacrifice far from home and in no way involved a defense of our native soil. For centuries, the Islamic states at the southern rim of the Mediterranean relied upon piracy to feed the coffers of their corrupt rulers. The state sponsored terrorists of that era (who claimed the romantic designation, “corsairs”) seized western shipping and sold their crews into unimaginably brutal slavery.

By the mid-eighteenth century, European powers learned to save themselves a great deal of trouble and wealth by bribing the local authorities with “tribute,” in return for which the pirates left their shipping alone. Until independence, British bribes protected American merchant ships in the Mediterranean since they traveled under His Majesty’s flag; after 1783, the new government faced a series of crises as Barbary pirates seized scores of civilian craft (with eleven captured in 1793 alone). Intermittently, the United States government paid tribute to escape these depredations: eventually providing a bribe worth more than $1,000,000—a staggering one-sixth of the total federal budget of the time – to the Dey of Algiers alone.

When Jefferson became president in 1801, he resolved to take a hard line against the terrorists and their sponsors. “I know that nothing will stop the eternal increase of demands from these pirates but the presence of an armed force, and it will be more economical & more honorable to use the same means at once for suppressing their insolencies,” he wrote.

The president dispatched nearly all ships of the fledgling American navy to sail thousands of miles across the Atlantic and through the straits of Gibraltar to do battle with the North African thugs. After a few initial reverses, daring raids on sea and land (by the new Marine Corps, earning the phrase in their hymn “….to the shores of Tripoli”) won sweeping victory. A decade later, with the U.S. distracted by the frustrating and inconclusive War of 1812 against Great Britain, the Barbary states again challenged American power, and President Madison sent ten new ships to restore order with another decisive campaign (known as “The Second Barbary War, 1815).

Continuing with the article:

The records of these dramatic, all-but-forgotten conflicts convey several important messages for the present day:

- The U.S. often goes to war when it is not directly attacked. One of the dumbest lines about the Iraq War claims that “this was the first time we ever attacked a nation that hadn’t attacked us.” Obviously, Barbary raids against private shipping hardly constituted a direct invasion of the American homeland, but founding fathers Jefferson and Madison nonetheless felt the need to strike back. Of more than 140 conflicts in which American troops have fought on foreign soil, only one (World War II, obviously) represented a response to an unambiguous attack on America itself. Iraq and Afghanistan are part of a long-standing tradition of fighting for U.S. interests, and not just to defend the homeland.

- Most conflicts unfold without a Declaration of War. Jefferson informed Congress of his determination to hit back against the North African sponsors of terrorism (piracy), but during four years of fighting never sought a declaration of war. In fact, only five times in American history did Congress actually declare war – the War of 1812, the Mexican War, The Spanish American War, World War I and World War II. None of the 135 other struggles in which U.S. troops fought in the far corners of the earth saw Congress formally declare war—and these undeclared conflicts (including Korea, Vietnam, the First Gulf War, and many more) involved a total of millions of troops and more than a hundred thousand total battlefield deaths.

- Islamic enmity toward the US is rooted in the Muslim religion, not recent American policy. In 1786, America’s Ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson, joined our Ambassador in London, John Adams, to negotiate with the Ambassador from Tripoli, Sidi Haji Abdrahaman. The Americans asked their counterpart why the North African nations made war against the United States, a power “who had done them no injury”, and according the report filed by Jefferson and Adams the Tripolitan diplomat replied: “It was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave; and that every mussulman who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise.”

- Cruel Treatment of enemies by Muslim extremists is a long-standing tradition. In 1793, Algerian pirates captured the merchant brig Polly and paraded the enslaved crewmen through jeering crowds in the streets of Algiers. Dey Hassan Pasha, the local ruler, bellowed triumphantly: “Now I have got you, you Christian dogs, you shall eat stones.” American slaves indeed spent their years of captivity breaking rocks. According to Max Boot in his fine book The Savage Wars of Peace: “A slave who spoke disrespectfully to a Muslim could be roasted alive, crucified, or impaled (a stake was driven through the arms until it came out at the back of the neck). A special agony was reserved for a slave who killed a Muslim – he would be cast over the city walls and left to dangle on giant iron hooks for days before expiring of his wounds.”

- There’s nothing new in far-flung American wars to defend U.S. economic interests. Every war in American history involved an economic motivation – at least in part, and nearly all of our great leaders saw nothing disgraceful in going to battle to defend the commercial vitality of the country. Jefferson and Madison felt no shame in mobilizing – and sacrificing – ships and ground forces to protect the integrity of commercial shipping interests in the distant Mediterranean. Fortunately for them, they never had to contend with demonstrators who shouted “No blood for shipping!”

- Even leaders who have worried about the growth of the U.S. military establishment came to see the necessity of robust and formidable armed forces. Jefferson and Madison both wanted to shrink and restrain the standing army and initially opposed the determination by President Adams to build an expensive new American Navy. When Jefferson succeeded Adams as president, however, he quickly and gratefully used the ships his predecessor built. The Barbary Wars taught the nation that there is no real substitute for military power, and professional forces that stand ready for anything.

- America has always played “the cop of the world.” In part, Jefferson and Madison justified the sacrifices of the Barbary Wars as a defense of civilization, not just the protection of U.S. interests – and the European powers granted new respect to the upstart nation that finally tamed the North African pirates. Jefferson and Madison may not have fought for a New World Order but they most certainly sought a more orderly world. Many American conflicts over the last 200 years have involved an effort to enfort to enforce international rules and norms as much as to advance national interests. Wide-ranging and occasionally bloody expeditions throughout Central America, China, the Philippines, Africa and even Russia after the Revolution used American forces to prevent internal and international chaos.

The Barbary Wars cost limited casualties for the United States (only 35 sailors and marines killed in action) but required the expenditure of many millions of dollars – a significant burden for the young and struggling Republic. Most importantly, these difficult battles established a long, honorable tradition of American power projected many thousands of miles beyond our shores. Those who claim that our engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan represent some shameful, radical departure from an old tradition of pacifism and isolation should look closely at the reality of our very first foreign war—and all the other conflicts in the intervening 200 years.

Religious Implications of the Treaty of Tripoli

A friend recently quoted this:

“As the government of the United States is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims]… it is declared… that no pretext arising from religious opinion shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries” …. “The United States is not a Christian nation any more than it is a Jewish or a Mohammedan nation.”

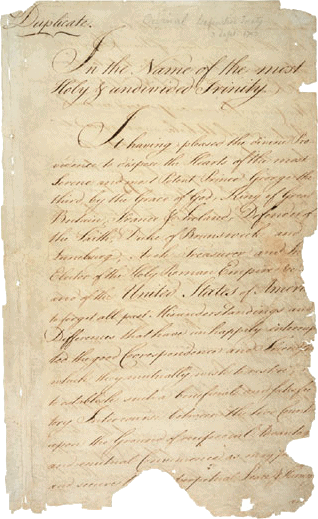

Firstly, those who cite the Treaty of Tripoli as evidence that this nation was not founded on the Christian religion, usually ignore the Treaty of Paris of 1783. This Treaty, negotiated by Ben Franklin and John Adams among others, is truly a foundational document for the United States, because by this Treaty Britian recognized the independence of the United States. The Treaty begins with the words, “In the Name of the most holy and undivided Trinity… ,” and there is no dispute about its validity or its wording. This “disputed validity” can be seen in the article by Tekton. A fuller dealing with the treaty can also be found at the Wall Builder’s site.

The United States Constitution and the American political system were based on Christian principles. Included in those Christian principles are the following theological and moral imperatives:

- Government power and sovereignty should be limited to the specific theological and moral commands of the Christian God.

- There should be a balance and separation of powers within the government so that a small group of evil people will be unable to tyrannize others.

- All citizens should have the right to own property and to buy and sell freely, according to the moral law of the Christian God.

- The right to life and property cannot be abridged without due process.

- The ultimate source of all authority lies with the God of the Bible.

- The American Government was designed to be a sacred covenant between the people, the state, and God. If the state breaks this covenant, then the people have the right, and the duty, to oppose the state but to use violence only as a last resort.

- As the Constitution clearly states, Jesus Christ is our Lord because He is the second member of the “most Holy and undivided Trinity.”

- Although the Constitution affirms a belief in the deity of Christ and in the Holy Trinity, neither the church nor the state is allowed to physically force people to believe these biblical teachings. The state should, however, do everything it can to facilitate the spread of the Christian Gospel and to place moral limits on the behavior of people.

For instance, one of many examples the Left gives for a secular founding of our nation is Benjamin Franklin. However, we can see his advice to his own kin in these quotes, he wrote to his daughter in 1764,

“Go constantly to church, whoever preaches. The act of devotion to the common prayer book is your principle business there, and if properly attended to, will do more towards amending the heart than sermons generally can do. For they were composed by men of much greater piety and wisdom, than our common composers of sermons can pretend to be; and therefore I wish you would never miss the prayer days; yet I do not mean you should despise sermons, even of the preachers you dislike, for the discourse is often much better than the man, as sweet and clear waters come through very dirty earth. I am the pore particular on this head, as you learned to express a little before I came away, some inclination to leave our church, which I would not have you do.”

And at age 84, when the President of Yale asked his opinion of Jesus of Nazareth, he replied that “I think his system of morals and his religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is likely to see.” Something in all the quotes on the atheist monument that are assumed to be “set in stone” (answered here in part 1):

Other posts in this series:

- Atheist Monument Critique: Madalyn Murray O’Hair

- Atheist Monument Critique: Treaty of Tripoli

- Atheist Monument Critique: Founding Father Freethinkers

- Atheist Monument Critique: Ten Commandments and Ten Punishments

Below, however, is my dealing with a signature (every time someone posts a response in a forum, you/they can choose to have the same “signature” display at the end of their comment — similar to email) of a person in a forum I was in a decade[+] ago. Enjoy, but again, I recommend the above linked articles as well as the one by Apologetic Press. You may ask why many apologetic sites deal with this? It is because atheists primarily latch on to this as an argument against the religious history of this nation. See also my paper on the Separation of Church and State.

Blancho’s signature states:

✂ “‘As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion…’ – Article XI of the English text of the Treaty of Tripoli, approved by the U.S. Senate on June 7, 1797 and ratified by President John Adams on June 10, 1797.”

(I have been wanting to address this quote for some time now, just haven’t had the time, sorry.)

How does this quote that Blancho uses fly in the face of other quotes by John Adams? What is the background to this treaty that caused such a signing to enter the record books of our hallowed halls. Let us first see a few quotes by Adams before we enter into the proper context of this treaty.

[speaking on why Christmas and the Fourth of July were out two top holidays] “Is it not that, in the chain of human events, the birthday of the nation is indissolubly linked with the birthday of the Saviour? That it forms a leading event in the progress of the gospel dispensation? Is it not that the Declaration of Independence first organized the social compact on the foundation of the Redeemer’s mission upon earth? That it laid the cornerstone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity?”

“Religion and virtue are the only foundations… of republicanism and of all free governments.”

Okay, the Treaty of Tripoli, one of several with Tripoli, was negotiated during the “Barbary Powers Conflict,” which began shortly after the Revolutionary War and continued through the Presidencies of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison. The Muslim Barbary Powers (Tunis, Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli, and Turkey) were warring against what they claimed to be the “Christian” nations (England, France, Spain, Denmark, and the United States). In 1801, Tripoli even declared war against the United States, thus constituting America’s first official war as an established independent nation.

Throughout this long conflict, the five Barbary Powers regularly attacked undefended American merchant ships. Not only were their cargoes easy prey but the Barbary Powers were also capturing and enslaving “Christian” seamen in retaliation for what had been done to them by the “Christians” of previous centuries (e.g., the Crusades and Ferdinand and Isabella’s expulsion of Muslims from Grenada).

In an attempt to secure a release of captured seamen and a guarantee of unmolested shipping in the Mediterranean, President Washington dispatched envoys to negotiate treaties with the Barbary nations. (Concurrently, he encouraged the construction of American naval warships to defend the shipping and confront the Barbary “pirates” – a plan not seriously pursued until President John Adams created a separate Department of the Navy in 1798.)

The American envoys negotiated numerous treaties of “Peace and Amity” with the Muslim Barbary nations to ensure “protection” of American commercial ships sailing in the Mediterranean. However, the terms of the treaty frequently were unfavorable to America, either requiring her to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars of “tribute” (i.e., official extortion) to each country to receive a guarantee” of safety or to offer other “considerations” (e.g., providing a warship as a gift to Tripoli, a gift frigate to Algiers, paying 525,000 to ransom captured American seamen from Algiers, etc.)

The 1797 treaty with Tripoli was one of the many treaties in which each country officially recognized the religion of the other in an attempt to prevent further escalation of a “Holy War” between Christians and Muslims. Consequently, Article XI of that treaty stated:

“As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion AS it has in itself no character of enmity [hatred] against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims] and as the said States [America] have never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan [Mohammedan] nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.”

This article may be read in two manners. It may, as its critics do, be concluded after the clause “Christian religion”; or it may be read in its entirety and concluded when the punctuation so indicates. But even if shortened and cut abruptly (“the government of the united states is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion”), this is not an untrue statement since it is referring to the Federal government.

Recall that while the Founders themselves openly described America as a Christian nation, they did include a constitutional prohibition against a federal establishment; religion was a matter left solely to the individual states. Therefore, if the article is read as a declaration that the federal government of the United States was not in any sense founded on the Christian religion, such a statement is not a repudiation of the fact that America was considered a Christian nation.

Reading the clause of the treaty in its entirety also fails to weaken this fact. Article XI simply distinguished America from those historical strains of European Christianity which held an inherent hatred of Muslims; it simply assured the Muslims that the United States was not a Christian nation like those of previous centuries (with whose practices the Muslims were very familiar) and thus would not undertake a religious holy war against them.

This latter reading is, in fact, supported by the attitude prevalent among numerous American leaders. The Christianity practiced in America was described by John Jay as “enlightened,” by John Quincy Adams as “civilized,” and by John Adams as “rational.” A clear distinction was drawn between American Christianity and that of European in earlier centuries.

As Noah Webster explained:

“The ecclesiastical establishments of Europe which serve to support tyrannical governments are not the Christian religion but abuses and corruption’s of it.”

Daniel Webster similarly explained that American Christianity was:

“Christianity to which the sword and the fagot [burning stake or hot branding iron] are unknown – general tolerant Christianity is the law of the land!”

While discussing the Barbary conflict with Jefferson, Adams declared:

“The policy of Christendom has made cowards of all their sailors before the standard of Mahomet. It would be heroical and glorious in us to restore courage to ours.”

Furthermore, it was Adams who declared:

“The general principles on which the fathers achieved independence were… the general principles of Christianity…. I will avow that I then believed, and now believe, that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God; and that those principles of liberty are as unalterable as human nature.”

Adams’ own words confirm that he rejected any notion that America was less than a Christian nation. Additionally, the writing’s of General William Eaton, a major figure in the Barbary Powers conflict, provide even more irrefutable testimony of how the conflict was viewed at that time. Eaton was first appointed by President John Adams a “Consul to Tunis,” and President Thomas Jefferson later advanced him to the position of “U. S. Naval Agent to the Barbary States,” authorizing him to lead a military expedition against Tripoli. Eaton’s official correspondence during his service confirms that the conflict was a Muslim war against a Christian America.

For example, when writing to Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, Eaton apprised him of why the Muslims would be such dedicated foes:

“Taught by revelation [the Koran] that war with the Christians will guarantee the salvation of their souls, and finding so great secular advantages in the observance of this religious duty [the secular advantage of keeping captured cargo], their [the Muslims’] inducements to desperate fighting are very powerful.”

Eaton later complained that after Jefferson had approved his plan for military action, he sent him the obsolete warship “Hero.” Eaton reported the impression of America made upon the Tunis Muslims when they saw the old warship and its few cannons:

“[T]he weak, the crazy situation of the vessel and equipage [armaments] tended to confirm an opinion long since conceived and never fairly controverted among the Tunisians, that the Americans are a feeble sect of Christianity.”

In a letter to Pickering, Eaton reported how pleased one Barbary ruler had been when he received the extortion compensations from America which had been promised him in one of the treaties, he said:

“To speak truly and candidly…. we must acknowledge to you that we have never received articles of the kind of so excellent a quality from any Christian nation.”

When John Marshall became the new Secretary of State, Eaton informed him:

“It is a maxim of the Barbary States, that ‘The Christians who would be on good terms with them must fight well or pay well.”

And when General Eaton finally commenced his military action against Tripoli, his personal journal noted:

“April 8th. We find it almost impossible to inspire these wild bigots with confidence in us or to persuade then that, being Christians, we can be otherwise than enemies to Musselmen. We have a difficult undertaking!”

May 23rd. Hassien Bey, the commander in chief of the enemy’s forces, has offered by private insinuation for my head six thousand dollars and double the sum for me as prisoner; and $30 per head for Christians. Why don’t he come and take it?”[/i][/list]Shortly after the military excursion against Tripoli was successfully terminated, its account was written and published. What was the title?

- The Life of the Late Gen. William Eaton… commander of the Christian and other forces… which Led to the Treaty of Peace Between The United States and The Regency of Tripoli

Context Blancho… context.

Here is the appendix from John Eidsmoe, Christianity and the Constitution: The Faith of Our Founding Fathers (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1987), 413-415, that will shed more light on this: