(originally posted June 2013)

What is the deadliest thing mankind has ever encountered in history? Disease, famine, nuclear weapons? Not even close. By sheer body count, it’s an idea. One that thrives on absolute power and control, and will stop at nothing to achieve complete domination. This is the story of the deadliest virus in the world, COMMUNISM. You can’t kill an idea, but ideas can kill you. We must fight this virus to survive.

You always hear that the right is fascist, WRONG! Here is a short clip from a documentary that is able to respond quite well to this charge. One should watch the whole DOCUMENTARY, its cheap enough. But this snippet can be used as a great — embeddable — answer to the left leaning challenge that Nazism and Marxism is any different.

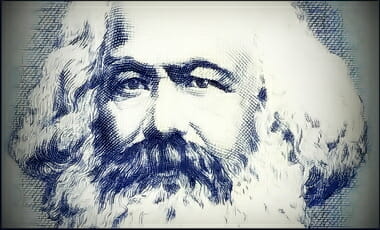

All quotes from THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF MARX AND ENGELS (also at MARX & FRIENDS IN THEIR OWN WORDS):

- “…the very cannibalism of the counterrevolution will convince the nations that there is only one way in which the murderous death agonies of the old society and the bloody birth throes of the new society can be shortened, simplified and concentrated, and that way is revolutionary terrorism.” — Karl Marx, “The Victory of the Counter-Revolution in Vienna,” Neue Rheinische Zeitung, 7 November 1848. (See entry of 29 Jan. 2007)

- “By the same right under which France took Flanders, Lorraine and Alsace, and will sooner or later take Belgium — by that same right Germany takes over Schleswig; it is the right of civilization as against barbarism, of progress as against stability. Even if the agreements were in Denmark’s favor — which is very doubtful-this right carries more weight than all the agreements, for it is the right of historical evolution.” — Friedrich Engels, Neue Rheinische Zeitung 10. Sep. 1848 (See entry of 8 Jan. 2005)

- “And as for the Jews, who since the emancipation of their sect have everywhere put themselves, at least in the person of their eminent representatives, at the head of the counter-revolution — what awaits them?” — – Karl Marx, Neue Rheinische Zeitung 17. Nov. 1848)

- “Every provisional political set-up following a revolution requires a dictatorship, and an energetic dictatorship at that.” — Karl Marx, Neue Rheinische Zeitung 14. Sep. 1848

(See entry of 9 Jan. 2005) - “Among all the nations and sub-nations of Austria, only three standard-bearers of progress took an active part in history, and are still capable of life — the Germans, the Poles and the Magyars. Hence they are now revolutionary. All the other large and small nationalities and peoples are destined to perish before long in the revolutionary holocaust. [“world storm” ? J.D.] For that reason they are now counter-revolutionary. …these residual fragments of peoples always become fanatical standard-bearers of counter-revolution and remain so until their complete extirpation or loss of their national character… [A general war will] wipe out all these racial trash [Völkerabfälle – original was given at Marxist websites as “petty hidebound nations” J.D.] down to their very names. The next world war will result in the disappearance from the face of the earth not only of reactionary classes and dynasties, but also of entire reactionary peoples. And that, too, is a step forward.” — Friedrich Engels, “The Magyar Struggle,” Neue Rheinische Zeitung, January 13, 1849

- “We discovered that in connection with these figures the German national simpletons and money-grubbers of the Frankfurt parliamentary swamp always counted as Germans the Polish Jews as well, although this dirtiest of all races, neither by its jargon nor by its descent, but at most only through its lust for profit, could have any relation of kinship with Frankfurt.” — Friedrich Engels, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, 29. Apr. 1849 (See entry of 17 Jan. 2005)

- “Germans and Magyars [of the Austro-Hungarian Empire] untied all these small, stunted and impotent little nations into a single big state and thereby enabled them to take part in a historical development from which, left to themselves, they would have remained completely aloof! Of course, matters of this kind cannot be accomplished without many a tender national blossom being forcibly broken. But in history nothing is achieved without violence and implacable ruthlessness… In short, it turns out these ‘crimes’ of the Germans and Magyars against the said Slavs are among the best and most praiseworthy deeds which our and the Magyar people can boast in their history.” — Friedrich Engels, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, 15 February 1849 (See the entry of 6 April 2005)

- “To the sentimental phrases about brotherhood which we are being offered here on behalf of the most counter-revolutionary nations of Europe, we reply that hatred of Russians was and still is the primary revolutionary passion among Germans; that since the revolution hatred of Czechs and Croats has been added, and that only by the most determined use of terror against these Slav peoples can we, jointly with the Poles and Magyars, safeguard the revolution. … Then there will be a struggle, an ‘unrelenting life-and-death struggle’ against those Slavs who betray the revolution; an annihilating fight and most determined terrorism – not in the interests of Germany, but in the interests of the revolution!” — Friedrich Engels, “Democratic Pan-Slavism” Neue Rheinische Zeitung 15. Feb. 1849 (See entry of 16 Jan. 2005 and 3 April 2005)

- “…only by the most determined use of terror against these Slav peoples can we, jointly with the Poles and Magyars, safeguard the revolution there will be a struggle, an ‘inexorable life-and-death struggle’, against those Slavs who betray the revolution; an annihilating fight and ruthless terror – not in the interests of Germany, but in the interests of the revolution!” — Friedrich Engels, “Democratic Pan-Slavism, Continued,” Neue Rheinische Zeitung, 16 February 1849 (See entry of 29 Jan. 2007)

- “We have no compassion and we ask no compassion from you. When our turn comes, we shall not make excuses for the terror.” — Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels “Suppression of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung”, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, May 19, 1849 (See entry of 29 Jan. 2007)

- “The workers… must try as much as ever possible to counteract all bourgeois attempts at appeasement, and compel the democrats to carry out their present terrorist phrases. They must act in such a manner that the revolutionary excitement does not collapse immediately after the victory. On the contrary, they must maintain it as long as possible. Far from opposing so-called excesses, such as sacrificing to popular revenge of hated individuals or public buildings to which hateful memories are attached, such deeds must not only be tolerated, but their direction must be taken in hand, for examples’ sake. …from the first moment of victory we must no longer direct our distrust against the beaten reactionary enemy, but against our former allies [the democratic forces], against the party who are now about to exploit the common victory for their own ends only. … The arming of the whole proletariat with rifles, guns, and ammunition should be carried out at once [and] the workers must … organize themselves into an independent guard, with their own chiefs and general staff, to put themselves under the order, not of the [new] Government, but of the revolutionary authorities set up by the workers. … Destruction of the influence of bourgeois democracy over the workers …[is a main point] which the proletariat, and therefore also the League, has to keep in eye during and after the coming upheaval. …to be able effectively to oppose the petty bourgeois democracy. In order that [the democratic party] whose betrayal of the workers will begin with the first hour of victory, should be frustrated in its nefarious work, it is necessary to organize and arm the proletariat.” — Karl Marx “Address to the Communist League” March 1850, cited in E. Burns (ed): A Handbook of Marxism 1935, p.66-68.

- “Removed and expelled members, like suspect individuals in general, are to be watched in the interest of the League, and prevented from doing harm. Intrigues of such individuals are at once to be reported to the community concerned.” — Rules written by Karl Marx and others for the Communist League (Art. 42) 1850 (See entry of 18 Jan. 2005)

- “Society is undergoing a silent revolution, which must be submitted to, and which takes no more notice of the human existences it breaks down than an earthquake regards the houses it subverts. The classes and the races, too weak to master the new conditions of life, must give way.” — Karl Marx, “Forced Emigration”, New York Tribune 1853 (See entry of 29 Jan. 2005)

- “Even with Europe in decay, still a war should have roused the healthy elements; a war should have awakened a lot of hidden powers, and surely so much energy would have been present among 250 million people that at least a respectable battle would have occurred, in which both parties could have reaped some honor, as much honor as courage and bravery can gain on the battlefield.” — Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, “The Boring War”, 1854 (See entry of 13 March 2005)

- “Those dogs of democrats and liberal riff-raff will see that we’re the only chaps who haven’t been stultified by the ghastly period of peace.” — Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels (Letter, 25 February 1859) (See entry of 11 Feb. 2005)

“Thus we find every tyrant backed by a Jew, as is every pope by a Jesuit. In truth, the cravings of oppressors would be hopeless, and the practicability of war out of the question, if there were not an army of Jesuits to smother thought and a handful of Jews to ransack pockets.

…the real work is done by the Jews, and can only be done by them, as they monopolize the machinery of the loan-mongering mysteries by concentrating their energies upon the barter trade in securities… Here and there and everywhere that a little capital courts investment, there is ever one of these little Jews ready to make a little suggestion or place a little bit of a loan. The smartest highwayman in the Abruzzi is not better posted up about the locale of the hard cash in a traveler’s valise or pocket than those Jews about any loose capital in the hands of a trader… The language spoken smells strongly of Babel, and the perfume which otherwise pervades the place is by no means of a choice kind.

Thus do these loans, which are a curse to the people, a ruin to the holders, and a danger to the governments, become a blessing to the houses of the children of Judah. This Jew organization of loan-mongers is as dangerous to the people as the aristocratic organization of landowners… The fortunes amassed by these loan-mongers are immense, but the wrongs and sufferings thus entailed on the people and the encouragement thus afforded to their oppressors still remain to be told.

The fact that 1855 years ago Christ drove the Jewish moneychangers out of the temple, and that the moneychangers of our age enlisted on the side of tyranny happen again chiefly to be Jews, is perhaps no more than a historical coincidence. The loan-mongering Jews of Europe do only on a larger and more obnoxious scale what many others do on one smaller and less significant. But it is only because the Jews are so strong that it is timely and expedient to expose and stigmatize their organization.”

— Karl Marx, “The Russian Loan”, New York Daily Tribune, 4 January 1856 (See entry of 20 May 2009)