(Originally posted December of 2015, Refreshed June of 2022)

OTHER POSTS DEALING WITH THIS IN SOME WAY:

- Bill Maher Goes 4-Rounds with Truth and Loses (Horus Edition)

- Bill Maher Gets “Religulouse” About Mithra (Oops A Daisy)

- Zeitgeist Refuted by Dr. Mark Foreman (RIP to the Z)

- Evidence OUTSIDE the Bible for Jesus (Bill Maher Added)

In this inaugural Cold-Case Christianity video broadcast / podcast, J. Warner re-examines an atheist objection related to the historicity of Jesus. Is Jesus merely a copycat of prior mythologies like Mithras, Osiris or Horus? How can we, as Christians, respond to such claims? Jim provides a five point response to this common atheist claim. (For more information, please visit www.ColdCaseChristianity.com)

Here are three segments of a pretty thorough refutation of the “copy-cat messiah” myth many in the gen Y and X generation have been influenced by.

Full Video Response HERE

I wish to point something out.

Very rarely do you find someone who is an honest enough skeptic that after watching the above 3 short videos asks questions like: “Okay, since my suggestion was obviously false, what would be the driving presuppositions/biases behind such a production?” “What are my driving biases/presuppositions that caused me to grab onto such false positions?” You see, few people take the time and do the hard work to compare and contrast ideas and facts. A good example of this is taken from years of discussing various topics with persons of opposing views, I often ask if they have taken the time to “compare and contrast.” Here is my example:

I own and have watched (some of the below are shown in high-school classes):

• Bowling for Columbine

• Roger and Me

• Fahrenheit 9/11

• Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price

• Sicko

• An Inconvenient Truth

• Loose Change

• Zeitgeist

• Religulouse

• The God Who Wasn’t There

• Super-Size Me

But rarely [really never] do I meet someone of the opposite persuasion from me that have watched any of the following (I own and have watched):

• Celsius41.11: The Temperature at Which the Brain Dies

• FahrenHYPE 9/11

• Michael & Me

• Michael Moore Hates America

• Bullshit! Fifth Season… Read More (where they tear apart the Wal-Mart documentary)

• Indoctrinate U

• Mine Your Own Business

• Screw Loose Change

• 3-part response to Zeitgeist

• Fat-Head

• Privileged Planet

• Unlocking the Mystery of Life

Continuing. Another point often overlooked is the impact the person who suggests the believer watch Zeitgeist thinks it will have.

Now that Zeitgeist has been shown to be very unsound and the history distorted, does the skeptic apply the same intended impact back upon him or herself? In other words, what is good for the goose is also good for the gander. Remember, the skeptic expects the Christian to watch this and come face-to-face with truth that undermines his or her’s faith, showing that they have a faith founded on something other than what they previously thought, an untruth. However, this intended outcome backfires and crumbles. The skeptic then has a duty [yes a duty] to apply intended impact onto one’s own biases and presuppositions and start to impose their own skepticism inward.

Christian historian and scholar Gary Habermas debates atheist Tim Callahan on the resurrection of Jesus. Callahan claims the resurrection of Jesus was influenced by pagan and Greek mythology, like Osiris, Dionysus, Adonis, Attis, etc. Of course, Callahan’s views are typical among so many young gullible atheists influenced by Richard Carrier and Robert Price. Habermas rips his claims to shreds in this debate.

A small excerpt from Mary Jo Sharp’s chapter, “Does the Story of Jesus Mimic Pagan Stories,” via, Paul Copan & William Lane Craig, eds., Come Let Us Reason: New Essays in Christian Apologetics (pp. 154-160, 164). Mary Jo has a website, CONFIDENT CHRISTIANITY.

OSIRIS

1. Osiris

While some critics of Christ’s story utilize the story of Osiris to demonstrate that the earliest followers of Christ copied it, these critics rarely acknowledge how we know the story of Osiris at all. The only full account of Osiris’s story is from the second-century Al) Greek writer, Plutarch: “Concerning Isis and Osiris.”[4] The other information is found piecemeal in Egyptian and Greek sources, but a basic outline can be found in the Pyramid Texts (c. 2686-c. 2160 BC). This seems problematic when claiming that a story recorded in the second century influenced the New Testament accounts, which were written in the first century. Two other important aspects to mention are the evolving nature of the Osirian myth and the sexual nature of the worship of Osiris as noted by Plutarch. Notice how just a couple of details from the full story profoundly strain the comparison of Osiris with the life of Christ.

Who was Osiris? He was one of five offspring born of an adulterous affair between two gods—Nut, the sky-goddess, and Geb earth-god.[5] Because of Nut’s transgression, the Sun curses her and will not allow her to give birth on any day in any month. However, the god Thoth[6] also loves Nut. He secures five more days from the Moon to add to the Egyptian calendar specifically for Nut to give birth. While inside his mother’s womb, Osiris falls in love with his sister, Isis. The two have intercourse inside the womb of Nut, and the resultant child is Horus.[7] Nut gives birth to all five offspring: Osiris, Horus, Set, Isis, and Nephthys.

Sometime after his birth, Osiris mistakes Nephthys, the wife of hisbrother Set, for his own wife and has intercourse with her. Enraged, Set plots to murder Osiris at a celebration for the gods. During the festivities, Set procures a beautiful, sweet-smelling sarcophagus, promising it as a gift to the attendee whom it might fit. Of course, this is Osiris. Once Osiris lies down in the sarcophagus, Set solders it shut and then heaves it into the Nile. There are at least two versions of Osiris’s fate: (a) he suffocates in the sarcophagus as it floats down the Nile, and (b) he drowns in the sarcophagus after it is thrown into the Nile.

Grief-stricken Isis searches for and eventually recovers Osiris’s corpse. While traveling in a barge down the Nile, Isis conceives a child by copulating with the dead body.[8] Upon returning to Egypt, Isis attempts to conceal the corpse from Set but fails. Still furious, Set dismembers his brother’s carcass into 14 pieces, which he then scatters throughout Egypt. A temple was supposedly erected at each location where a piece of Osiris was found.

Isis retrieves all but one of the pieces, his phallus. The body is mummified with a model made of the missing phallus. In Plutarch’s account of this part of the story, he noted that the Egyptians “presently hold a festival” in honor of this sexual organ.[9] Following magical incantations, Osiris is raised in the netherworld to reign as king of the dead in the land of the dead. In The Riddle of Resurrection: Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East, T. N. D. Mettinger states: “He both died and rose. But, and this is most important, he rose to continued life in the Netherworld, and the general connotations are that he was a god of the dead.”[10] Mettinger quotes Egyptologist Henri Frankfort:

Osiris, in fact, was not a dying god at all but a dead god. He never returned among the living; he was not liberated from the world of the dead,… on the contrary, Osiris altogether belonged to the world of the dead; it was from there that he bestowed his blessings upon Egypt. He was always depicted as a mummy, a dead king.[11]

This presents a very different picture from the resurrection of Jesus, which was reported as a return to physical life.

HORUS

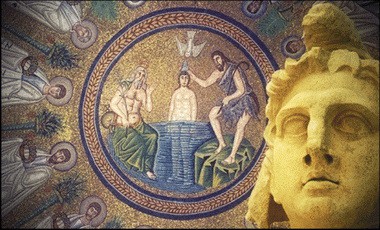

2. Horus

Horus’s story is a bit difficult to decipher for two main reasons. Generally, his story lacks the amount of information for other gods, such as Osiris. Also, there are two stories concerning Horus that develop and then merge throughout Egyptian history: Horus the Sun-god, and Horus the child of Isis and Osiris. The major texts for Horus’s story are the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, the Book of the Dead, Plutarch, and Apuleius-all of which reflect the story of Horus as the child of Isis and Osiris.[12] The story is routinely found wherever the story of Osiris is found.

Who was Horus? He was the child of Isis and Osiris. His birth has several explanations as mentioned in Isis and Osiris’s story: (1) the result of the intercourse between Isis and Osiris in Nut’s womb; (2) conceived by Isis’s sexual intercourse with Osiris’s dead body; (3) Isis is impregnated by Osiris after his death and after the loss of his phallus; or (4) Isis is impregnated by a flash of lightning.[13] To protect Horus from his uncle’s rage against his father, Isis hides the child in the Delta swamps. While he is hiding, a scorpion stings him, and Isis returns to find his body lifeless. (In Margaret Murray’s account in The Splendor That Was Egypt, there is no death story here, but simply a poisoned child.) Isis prays to the god Ra to restore her son. Ra sends Thoth, another Egyptian god, to impart magical spells to Isis for the removal of the poison. Thus, Isis restores Horus to life. The lesson for worshippers of Isis is that prayers made to her will protect their children from harm and illness. Notice the outworking of this story is certainly not a hope for resurrection to new life, in which death is vanquished forever as is held by followers of Jesus.[14] Despite this strain on the argument, some still insist that Horus’s scorpion poisoning is akin to the death and resurrection of Jesus.

In a variation of Horus’s story, he matures into adulthood at an accelerated rate and sets out to avenge his father’s death. In an epic battle with his uncle Set, Horus loses his left eye, and his uncle suffers the loss of one part of his genitalia. The sacrifice of Horus’s eye, when given as an offering before the mummified Osiris, is what brings Osiris new life in the underworld.[15] Horus’s duties included arranging the burial rites of his dead father, avenging Osiris’s death, offering sacrifice as the Royal Sacrificer, and introducing recently deceased persons to Osiris in the netherworld as depicted in the Hunefer Papyrus (1317-1301 BC). One aspect of Horus’s duties as avenger was to strike down the foes of Osiris. This was ritualized through human sacrifice in the first dynasty, and then, eventually, animal sacrifice by the eighteenth dynasty. In the Book of the Dead we read of Osiris, “Behold this god, great of slaughter, great of fear! He washes in your blood, he bathes in your gore!”[16] So Horus, in the role of Royal Sacrificer, bought his own life from this Osiris by sacrificing the life of other. There is no similarity here to the sacrificial death of Jesus.

MITHRA

(MORE BELOW – JUMP)

3. Mithras

There are no substantive accounts of Mithras’s story, but rather a pieced-together story from inscriptions, depictions, and surviving Mithraea (man-made caverns of worship). According to Rodney Stark, professor of social sciences at Baylor University, an immense amount of “nonsense” has been inspired by modern writers seeking to “decode the Mithraic mysteries.”[17] The reality is we know very little about the mystery of Mithras or its doctrines because of the secrecy of the cult initiates. Another problematic aspect is the attempt to trace the Roman military god, Mithras, back to the earlier Persian god, Mithra, and to the even earlier Indo-Iranian god, Mitra. While it is plausible that the latest form of Mithraic worship was based on antecedent Indo-Iranian traditions, the mystery religion that is compared to the story of Christ was a “genuinely new creation?”[18] Currently, some popular authors utilize the Roman god’s story from around the second century along with the Iranian god’s dates of appearance (c. 1500-1400 BC).

This is the sort of poor scholarship employed in popular renditions of Mithras, such as in Zeitgeist: The Movie. For the purpose of summary, we will utilize the basic aspects of the myth as found in Franz Cumont’s writing and note variations, keeping in mind that many Mithraic scholars question Cumont, as well as one another, as to interpretations and aspects of the story.[19] Thus, we will begin with Cumont’s outline.

Who was Mithra? He was born of a “generative rock,” next to a river bank, under the shade of a sacred tree. He emerged holding a dagger in one hand and a torch in the other to illumine the depths from which he came. In one variation of his story, after Mithra’s emergence from the rock, he clothed himself in fig leaves and then began to test his strength by subjugating the previously existent creatures of the world. Mithra’s first activity was to battle the Sun, whom he eventually befriended. His next activity was to battle the first living creature, a bull created by Ormazd (Ahura Mazda). Mithra slew the bull, and from its body, spine, and blood came all useful herbs and plants. The seed of the bull, gathered by the Moon, produced all the useful animals. It is through this first sacrifice of the first bull that beneficent life came into being, including human life. According to some traditions, this slaying took place in a cave, which allegedly explains the cave-like Mithraea.[20]

Mit(h)ra’s name meant “contract” or “compact.”[21] He was known in the Avesta—the Zoroastrian sacred texts—as the god with a hundred ears and a hundred eyes who sees, hears, and knows all. Mit(h)ra upheld agreements and defended truth. He was often invoked in solemn oaths that pledged the fulfillment of contracts and which promised his wrath should a person commit perjury. In the Zoroastrian tradition, Mithra was one of many minor deities (yazatas) created by Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity. He was the being who existed between the good Ahura Mazda and the evil Angra Mainyu—the being who exists between light and darkness and mediates between the two. Though he was considered a lesser deity to Ahura Mazda, he was still the “most potent and most glorious of the yazata.”[22]

The Roman version of this deity (Mithras) identified him with the light and sun. However, the god was not depicted as one with the sun, rather as sitting next to the sun in the communal meal. Again, Mithras was seen as a friend of the sun. This is important to note, as a later Roman inscription (c. AD 376) touted him as “Father of Fathers” and “the Invincible Sun God Mithras.”[23] Mithras was proclaimed as invincible because he never died and because he was completely victorious in all his battles. These aspects made him an attractive god for soldiers of the Roman army, who were his chief followers. Pockets of archaeological evidence from the outermost parts of the Roman Empire reinforce this assumption. Obviously, some problems arise in comparing Mithras to Christ, even at this level of simply comparing stories. Mithras lacks a death and therefore also lacks a resurrection.

Now that we have a more comprehensive view of the stories, it is quite easy to discern the vast difference between the story of Jesus and even the basic story lines of the commonly compared pagan mystery gods. One must only use the very limited, general aspects of the stories to make the accusation of borrowing, while ignoring the numerous aspects having nothing in common with Jesus’ story, such as missing body parts, sibling sexual intercourse inside the womb of a goddess-mother, and being born from a rock. This is why it is important to get the whole story. The supposed similarities are quite flimsy in the fuller context.

Just three excerpts from Edwin Yamauchi’s book, Persia and the Bible, These three pics are a bit unrelated… but the topic is on Mithras and their dating of the reliefs known to us. If you take the time to read Dr. Yamauchi’s chapter linked, you can see the connection to the above portion by Mary Jo. (The entire chapter on MITHRAISM can be read HERE.)

FOOTNOTES FROM BOXES “A” “B” “C”

[4] Plutarch, “Concerning Isis and Osiris,” in Hellenistic Religions: The Age of Syncretism, ed. Frederick C. Grant (Indianapolis: Liberal Arts Press, 1953), 80-95.

[5] In some depictions, Nut and Geb are married. Plutarch’s account insinuates that they have committed adultery because of the anger of the Sun at Nut’s transgression.

[6] Plutarch refers to Thoth as Hermes in “Concerning Isis and Osiris.”

[7] Plutarch’s “Concerning Isis and Osiris” appears to be the only account with this story of Horus’s birth.

[8] This aspect of the story, which was a variation of Horus’s conception story, is depicted in a drawing from the Osiris temple in Dendara.

[9] Plutarch, “Concerning Isis and Osiris,” 87.

[10] N. D. Mettinger, The Riddle of Resurrection: Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 2001), 175.

[11] Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature (Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 190, 289; cf. 185; cited in Mettinger, Riddle of Resurrection, 172.

[12] For the purposes of this chapter, I use the following sources and translations: E. A. Wallis Budge’s translation of the Book of the Dead; Plutarch’s “Concerning Isis and Osiris”; Joseph Campbell’s piecing together of the story in The Mythic Image; as well as other noted interpretations of the story.

[13] The latter two versions of Horus’s birth can be found in Rodney Stark, Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief (New York: Harper Collins, 2007), 204. However, Stark does not reference the source for these birth stories.

[14] The development of Isis’s worship as a protector of children is a result of this instance; Margaret A. Murray, The Splendor That Was Egypt, rev. ed. (Mineola: Dover, 2004), 106.

[15] Joseph Campbell, The Mythic Image (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974), 29, 450.

[16] Murray, The Splendor That Was Egypt, 103.

[17] Stark, Discovering God, 141.

[18] Roger Beck, “The Mysteries of Mithras: A New Account of Their Genesis,” Journal of Roman Studies 88 (1998): 123.

[19] Roger Beck, M. J. Vermaseren, David Ulansey, N. M. Swerdlow, Bruce Lincoln, John R Hinnells, and Reinhold Merkelbach, for example.

[20] More corecontemporary Mithraic scholars have pointed to the lack of a bull-slaying story in the Iranian version of Mithra’s story: “there is no evidence the Iranian god ever had anything to do with a bull-slaying.” David Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 8; see Bruce Lincoln, “Mitra, Mithra, Mithras: Problems of a Multiform Deity,” review of John R. Hinnells, Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, in History of Religions 17 (1977): 202-3. For an interpretation of the slaying of the bull as a cosmic event, see Luther H. Martin, “Roman Mithrraism and Christianity,” Numen 36 (1989): 8.

[21] “For the god is clearly and sufficiently defined by his name. `Mitra means ‘con-tract’, as Meillet established long ago and D. [Professor G. Dumezi] knows but keeps forgetting.” Ilya Gershevitch, review of Mitra and Aryaman and The Western Response to Zoroaster, in the Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 22 (1959): 154. See Paul Thieme, “Remarks on the Avestan Hymn to Mithra,”Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 23 (1960): 273.

[22] Franz Cumont, The Mysteries of Mithra: The Origins of Mithraism (1903). Accessed on May 3,2008, http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/mom/index.htm.

[23] Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI. 510; H. Dessau, Inscriptions Latinae Selectae II. 1 (1902), No. 4152, as quoted in Grant, Hellenistic Religions, 147. This inscription was found at Rome, dated August 13, AD 376. Notice the late date of this title for Mithras—well after Christianity was firmly established in Rome.

Another good source is: “Jesus Vs Mithra – Debunking The Alleged Parallels“

Dr. William Lane Craig

On Thursday, April 10th, 2014 Dr William Lane Craig spoke on the “Objective Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus” at Yale University. Dr. Craig is one of the leading theologians and defenders of Jesus’ resurrection, demonstrating the veracity of his divinity. This is the biggest claim in history! After the lecture, Dr Craig had a lengthy question and answer time with students from Yale. In this video, Dr Craig answers the question, “What about pre-Christ resurrection myths?”

Dr. William Lane Craig answers the question: Is Jesus’ life parallel to the story of Osiris and Horus?

Edwin Yamauchi (education), wrote one of the best books about Biblical history I have read. Persia and the Bible. Beneath the Bill Maher critique is a photocopy portion of his chapter on Mithraism. Enjoy.

BILL MAHER

PURCHASE THE BOOK, it is a must for a Christian scholars library: Amazon | LOGOS