Lutheran Hour Ministries (2017) – From Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517 to the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, God was at work in the Reformation. Fierce debates over Scripture, church doctrine, and late medieval church practice led to theological positions articulating salvation as God’s grace in action, with man being left to add nothing to his own salvation. In A Man Named Martin – Part 3: The Movement, viewers will see how the Reformation transformed European society and, eventually, left a profound impression around the globe.

Church History

The “Office” of Marriage and Love in the Reformation

The reformers’ early preoccupation with marriage was driven, in part, by their jurisprudence. The starting assumption of the budding Lutheran theories of law, society, and politics was that the earthly kingdom was governed by the three natural estates of household, Church, and state. Hausvater, Gottesvater, and Landesvater; paterfamilias, patertheologicus, and patapofiticus— these were the three natural offices through which God revealed Himself and reflected His authority in the world. These three offices and orders stood equal before God and before each other. Each was called to discharge essential tasks in the earthly kingdom without impediment or interference from the other. The reform of marriage, therefore, was as important as the reform of the Church and the state. Indeed, marital reform was even more urgent, for the marital household was, in the reformers’ view, the “oldest,” “most primal,” and “most essential” of the three estates, yet the most deprecated and subordinated of the three. Marriage is the “mother of all earthly laws,” Luther wrote, and the source from which the Church, the state, and other earthly institutions flowed. “God has most richly blessed this estate above all others, and in addition, has bestowed on it and wrapped up in it everything in the world, to the end that this estate might be well and richly provided for. Married life therefore is no jest or presumption; it is an excellent thing and a matter of divine seriousness.”

The reformers’ early preoccupation with marriage was driven, in part, by their politics. A number of early leaders of the Reformation faced aggressive prosecution by the Catholic Church and its political allies for violation of the canon law of marriage and celibacy. Among the earliest Protestant leaders were ex-priests and ex-monastics who had forsaken their orders and vows, and often married shortly thereafter. Indeed, one of the acts of solidarity with the new Protestant cause was to marry or divorce in open violation of the canon law and in defiance of a bishop’s instructions. This was not just an instance of crime and disobedience. It was an outright scandal, particularly when an ex-monk such as Brother Martin Luther married an ex-nun such as Sister Katherine von Bora —a prima facie case of spiritual incest As Catholic Church courts began to prosecute these canon law offenses, Protestant theologians and jurists rose to the defense of their co-religionists, producing a welter of briefs, letters, sermons, and pamphlets that denounced traditional norms and pronounced a new theology of marriage.

Evangelical theologians treated marriage not as a sacramental institution of the heavenly kingdom, but as a social estate of the earthly kingdom. Marriage was a natural institution that served the goods and goals of mutual love and support of husband and wife, procreation and nurture of children, and mutual protection of spouses from sexual sin. All adults, preachers and others alike, should pursue the calling of marriage, for all were in need of the comforts of marital love and of protection from sexual sin. When properly structured and governed, the marital household served as a model of authority charity, and pedagogy in the earthly kingdom and as a vital instrument for the reform of Church, state, and society. Parents served as “bishops” to their children. Siblings served as priests to each other. The household altogether — particularly the Christian household of the married minister — was a source of “evangelical impulses” in society.

Though divinely created and spiritually edifying, however, marriage and the family remained a social estate of the earthly kingdom. All parties could partake of this institution, regardless of their faith. Though subject to divine law and clerical counseling, marriage and family life came within the ,jurisdiction of the magistrate, not the cleric; of the civil law, not the canon law. The magistrate, as God’s vice-regent of the earthly kingdom, was to set the laws for marriage formation, maintenance, and dissolution; child custody, care, and control; family property, inheritance, and commerce.

Political leaders rapidly translated this new Protestant gospel into civil law. Just as the civil act of marriage often came to signal a person’s conversion to Protestantism, so the Civil Marriage Act came to symbolize a political community’s acceptance of the new Evangelical theology. Political leaders were quick to establish comprehensive new marriage laws for their polities, sometimes building on late medieval civil laws that had already controlled some aspects of this institution. The first reformation ordinances on marriage and family life were promulgated in 1522. More than sixty such laws were on the books by the time of Luther’s death in 1546. The number of new marriage laws more than doubled again in the second half of the sixteenth century in Evangelical portions of Germany. Collectively, these new Evangelical marriage laws: (1) shifted primary marital jurisdiction from the Church to the state; (2) strongly encouraged the marriage of clergy; (3) denied that celibacy, virginity, and monasticism were superior callings to marriage; (4) denied the sacramentality of marriage and the religious tests and impediments traditionally imposed on its participants; (5) modified the doctrine of consent to betrothal and marriage, and required the participation of parents, peers, priests, and political officials in the process of marriage formation; (6) sharply curtailed the number of impediments to betrothal and putative marriages; and (7) introduced divorce, in the modern sense, on proof of adultery, malicious desertion, and other faults, with a subsequent right to remarriage at least for the innocent party. These changes eventually brought profound and permanent change to the life, lore, and law of marriage in Evangelical Germany.

John Witte, Jr., Law and Protestantism: The Legal Teachings of the Lutheran Reformation (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 200-202.

God’s Ideal Should Be Mine

Persons should accept marriage not only as a duty that served society, but also as a remedy against sexual sin. Since the fall into sin, lust has pervaded the conscience of every person, the Lutheran reformers insisted. Marriage has become an absolute necessity of sinful humanity, for without it, the person’s distorted sexuality becomes a force capable of overthrowing the most devout conscience. A person is enticed by his or her own nature to prostitution, masturbation, voyeurism, homosexuality, and sundry other sinful acts. The gift of marriage, Luther wrote, should be declined only by those who have received God’s gift of continence. “Such persons are rare, not one in a thousand, for they are a special miracle of God.” The Apostle Paul has identified this group as the permanently impotent and the eunuchs; few others can claim such a unique gift.

This understanding of the created origin and purpose of marriage un-dergirded the reformers’ bitter attack on celibacy and monasticism. To require celibacy of clerics, monks, and nuns was beyond the authority of the church and ultimately a source of great sin. Celibacy was for God to give, not for the church to require. It was for each individual, not for the church, to decide whether he or she had received this gift. By demanding monastic vows of chastity and clerical vows of celibacy, the church was seen to be intruding on Christian freedom and violating scripture, nature, and common sense. By institutionalizing and encouraging celibacy the church was seen to prey on the immature and the uncertain. By holding out food, shelter, security, and opportunity, the monasteries enticed poor and needy parents to condemn their children to celibate monasticism. Mandatory celibacy, Luther taught, was hardly a prerequisite to true service of God. Instead, it led to “great whoredom and all manner of fleshly impurity and… hearts filled with thoughts of women day and night.” For the consciences of Christians and non-Christians alike are infused with lust, and a life of celibacy and monasticism only heightens the temptation.

John Witte, Jr., From Sacrament to Contract: Marriage, Religion, and Law in the Western Tradition (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), 50.

Hank Hanegraaff’s Conversion (Friel, White, Craig)

(A good quick summation of Orthodoxy can be found here at GOT QUESTIONS) Here is WRETCHED’s take:

(Below) A two hour program today playing nearly 50 minutes worth of comments (ok, at 1.2x speed!) by Hank Hanegraaff relating to his conversion to Eastern Orthodoxy and asking the simple question: can an Eastern Orthodox believer function as the Bible Answer Man? Important issues to be sure!

I have to include this discussion by William Lane Craig on the matter:

The Apocrypha vs. Jesus

(I change the links to the Scripture references from their original source.) While there are many reasons to reject the Apocrypha as on par with Scripture, the main reason is the testimony of Christ. Here for instance is an article from the BLUE LETTER BIBLE by Don Stewart (a co-author on many works with Josh McDowell) giving 27-reasons to reject the Apocrypha as equal to Scripture… the most important point being his #27:

27. JESUS’ TESTIMONY IS DEFINITIVE

It is clear that in the first century the Old Testament was complete. Jesus put His stamp of approval on the books of the Hebrew Old Testament but said nothing concerning the Apocrypha. However, He did say that the Scriptures were the authoritative Word of God and they could not be broken. Any adding to that which God has revealed is denounced in the strongest of terms. Jesus asked the religious leaders a penetrating question.

Why do you break the command of God for the sake of your tradition? (Matthew 15:3).

Jesus’ And The Extent Of The Old Testament

A statement by Jesus seemingly gives His belief in the extent of the Old Testament.

Therefore I send you prophets, sages, and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your synagogues and pursue from town to town, so that upon you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah son of Barachiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. Truly I tell you, all this will come upon this generation (Matthew 23:34-36).

He mentions Abel and Zechariah as the first and last murder messengers of God that were murdered. Abel’s murder is mentioned in Genesis while Zechariah’s was in 2 Chronicles – the last Old Testament book in the Hebrew canonical order. The fact that these two are specifically mentioned is particularly significant. There other murders of God’s messengers recorded in the Apocrypha. Jesus does not mention them. This strongly suggests He did not consider the books of the Apocrypha as part of Old Testament Scripture as with the books from Genesis to 2 Chronicles.

THERE WAS MORE TESTIMONY FROM JESUS

Jesus gave further testimony of the extent of the Old Testament canon in the day of His resurrection. He said.

How foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! . . . And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself (Luke 24:25,27).

Note Jesus’ emphasis on “all that the prophets had spoken.” Later He explained the extent of “all that the prophets had said.”

He said to them, “This is what I told you while I was still with you: Everything must be fulfilled that is written about me in the Law of Moses, the Prophets and the Psalms” (Luke 24:44).

This is a reference to the threefold division of the Hebrew Scripture. They constitute “all that the prophets said.” There is no reference to the Apocrypha. It would not have been part of the threefold division of the Old Testament.

So, even if an early church father thought the Apocrypha should be included as Holy Scripture, he would be wrong (see also CARM). STAND TO REASON basis their article on the matter on this point by Jesus:

Should the Bible include the Apocrypha? Here is where I think Jesus can help. Specifically, I believe Jesus’ words lead us to the conclusion that the Apocrypha is not Scripture.

During one of His heated discussions with the Pharisees and the lawyers, Jesus says,

Therefore also the Wisdom of God said, “I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute,’ so that the blood of all the prophets, shed from the foundation of the world, may be charged against this generation, from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. Yes, I tell you, it will be required of this generation.” Woe to you lawyers! For you have taken away the key of knowledge. You did not enter yourselves, and you hindered those who were entering. (Luke 11:49–51)

First, notice that Jesus mentions the blood of all the prophets. He’s not talking about some of the prophets. He’s talking about the blood of all the prophets since that foundation of the world. Next, Jesus limits who He includes with “all the prophets.” He gives us some bookends for identifying these prophets. In verse 50, Jesus says, “…from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah.”

Abel is the very first prophet to die for his faith. The death of Abel is recorded in Genesis—the first book of the Jewish Scriptures. Jesus also cites the death of Zechariah as the last prophet to die. However, this isn’t right. Zechariah isn’t the last prophet to die. Chronologically speaking, Uriah—the son of Shemaiah—is the last prophet killed. You can read about his death in Jeremiah 26:20–23.

So why does Jesus list Zechariah as the last prophet to die? The reason is crucial to why we shouldn’t accept the Apocrypha as Scripture. Jesus chose Abel first and Zachariah last because they were the first and last prophets martyred in the Jewish Scriptures. The Jews of Jesus’ day would have known that Zechariah’s death is recorded in Chronicles—the last book of the Jewish Scriptures. It reads,

Then the Spirit of God clothed Zechariah the son of Jehoiada the priest, and he stood above the people, and said to them, “Thus says God, ‘Why do you break the commandments of the Lord, so that you cannot prosper? Because you have forsaken the Lord, he has forsaken you.’” But they conspired against him, and by command of the king they stoned him with stones in the court of the house of the Lord. (2 Chronicles 24:20–21)

Therefore, Jesus limits “all the prophets” to the Jewish Scriptures—from Genesis to Chronicles. It was the prophets contained in the Jewish Scriptures, and no others, who were responsible for communicating God’s word until the time of Christ. The author of Hebrews writes, “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days He has spoken to us by his Son, whom He appointed the heir of all things, through whom also He created the world” (Hebrews 1:1–2)….

Oh, BTW, I am a big fan of that guy, Jesus.

Tradition: Catholic/Protestant Views

Gregg Allison and Chris Castaldo, The Unfinished Reformation: What Unites and Divides Catholics and Protestants After 500 Years (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2016), 68-72.

…. How does God speak to the world through such revelation? A major difference between Catholics and Protestants is found in the answer to this question.

Catholics affirm that God speaks to the world through Tradition and Scripture. Similar to the twofold way that Jesus’ apostles communicated the gospel—orally, through preaching, and in writing, through the biblical text—so God communicates to his people today in a twofold pattern: the teaching, or Tradition, of the Church’s bishops, who are the successors of the apostles, and Scripture. “Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture are bound closely together and communicate one with the other. For both of them, flowing out of the same divine well-spring, come together in some fashion to form one thing and move toward the same goal” (CCC 80). Thus, these two modes are two streams of one source of divine authority.

Tradition is “the Word of God which has been entrusted to the apostles by Christ the Lord and the Holy Spirit” (CCC 81). This oral communication was in turn handed over by the apostles to their successors, the bishops of the Church, who maintain this Tradition and, on occasion, proclaim it as Church doctrine. For example, the Church declares the immaculate conception of Mary and her bodily assumption (to be treated later) as part of Tradition. The other mode of divine revelation is Scripture. Though Catholics and Protestants stand together in their belief that the Bible is the God-breathed, written revelation of God, they part company on many other points in their understanding of Scripture. Significantly, the Catholic Church “does not derive her certainty about all revealed truths from the holy Scriptures alone. Both Scripture and Tradition must be accepted and honored with equal sentiments of devotion and reverence” (CCC 82).

Against the Catholic affirmation of Scripture and Tradition as authoritative divine revelation, Protestants assert the principle of sola Scriptura: Scripture, and Scripture alone, is authoritative divine revelation. God speaks to the world through his Word, which is written Scripture only, not Scripture plus Tradition. This Protestant critique of Tradition is grounded on several points.

First, Protestants believe that the Catholic position has thin biblical support. For example, to buttress their position, Catholics appeal to Jesus’ explanation to his disciples: “I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now” (John 16:12). They claim this passage as an example of Jesus underscoring the necessity of both Scripture and Tradition—what he could reveal to them as he was speaking with them, and what he would need to reveal to them later, when they were able to absorb it.

The Protestant response insists that this interpretation misses the point of that interaction. It is simply telling us that as Jesus was speaking with his disciples, they could not grasp his revelation—what he was saying to them at that moment. Indeed, in short order, they would express utter confusion about his impending death (John 16:16-24). Even when they thought they could understand the unfolding calamity, Jesus informed them that they would all abandon him (John 16:25-33), and soon afterward devil-prompted Judas was poised to betray him (John 13:2; 18:1-8), and Peter denied ever knowing Jesus (John 18:15-18, 25-27).

Following Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, however, the disciples received the Holy Spirit. As Jesus had promised, the Spirit taught the disciples all things, brought to their remembrance all that Jesus had said to them, and guided them into all the truth (John 14:26; 16:13). Having removed the prior dullness and ignorance that had characterized the disciples, the Holy Spirit moved those who wrote Scripture to communicate the whole of divine revelation (our New Testament). This work was exactly what Jesus taught about his sending the Holy Spirit to inspire them to write Scripture. Protestants believe that, understood in context, there was no need for supplemental communication—Tradition—alongside of Scripture.1

Second, Protestants believe that the Catholic view has thin historical support as well. It is true that the apostles communicated the gospel both orally, through their preaching, and eventually in writing, through the New Testament. But when Paul points out “so then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter” (2 Thess. 2:15), he is not saying that his oral teaching and his written communication consisted of different revelations which supplement each other. On the contrary, these two delivery systems presented the same divine revelation. The difference was in the form, not the content.

The early church did have a type of tradition: the doctrine that the apostles transmitted provided a proper understanding of Scripture and underscored sound doctrine. It stood in opposition to the wrong biblical interpretations of the time and the misguided beliefs of heretics. The early church’s “rule of faith” or “canon (standard) of truth” was a summary of its essential doctrines based on Scripture. The early creeds—for example, the Apostles’ Creed and the Chalcedonian Creed—affirmed the doctrines of the Trinity and of Christ derived very carefully from Scripture. Protestants embrace this type of tradition, finding it to be a fine source of wisdom from the past. But this is far from the Catholic notion of Tradition.

In fact, it was not until the fourteenth century that the Catholic Church began to make novel claims about Tradition, granting unwritten communication by Church leaders authoritative status as doctrine outside of, and in addition to, Scripture. Such an idea of Tradition is a relatively late development and is quite different from the notion as found in Scripture and in the early church.2

Standing opposed to the Catholic view of Scripture and Tradition as two modes of divine revelation, Protestants hold to the sufficiency and necessity of Scripture. Scripture is sufficient in that it provides everything that people need to be saved from sin and death, and everything that Christians need to please God fully. Specifically, God-breathed Scripture equips believers “for every good work” (2 Tim. 3:16-17). Protestants see doctrines like the immaculate conception and bodily assumption of Mary as unnecessary and unbiblical. Protestants don’t need these doctrines to possess and believe the fullness of divine revelation. They don’t need practices like the sacrament of penance and praying for the dead in order to know and do all that God requires of them. They don’t need to believe that when they take the Lord’s Supper, the bread and the wine are transubstantiated into the body and blood of Christ. These doctrines, practices, and beliefs are extra-biblical, not from Scripture alone. Thus, Scripture’s sufficiency and the principle of sola Scriptura—”Scripture alone”—are closely connected and contradict the need for Catholic Tradition.3

Scripture is necessary in that it is essential for knowing the way of salvation, for progressing in godliness, and for understanding God’s will. To put it another way, apart from Scripture there can be no awareness of salvation, growth in holiness, and knowledge of God’s will.4 Catholics, on the other hand, would maintain that Scripture is necessary for the well-being of the Church: for the Church to be robustly all that God intends it to be, Scripture is necessary. But Catholics would not hold that Scripture is necessary for the being of the Church: if Scripture were to be lost, the Church could still exist because it would still have Tradition, part of divine revelation. Protestants insist that the Church would lose its way without Scripture: if Scripture were to be lost, the Church would cease to exist because all of divine revelation would have disappeared.

How does God speak to the world? Catholics respond to this question by saying “through Scripture and Tradition.” Protestants reply, “through Scripture alone.”

FOOTNOTES 1. This affirmation does not mean that Protestantism ignores or rejects the theological wisdom that it has inherited from the church throughout the ages (a point to be made shortly). 2. Factors that contributed to this development included: (1) exaggerated and indefensible claims for papal authority not only over the Catholic Church but the entire world as well; (2) theoretical debates over which of the two options—the authority of Scripture and the authority of the Church—is supreme; (3) the introduction of the idea of apostolic succession; and (4) the novel claim that, because the Church had determined the canon of Scripture, the Church therefore possesses special revelation that is not found in Scripture. See Gregg R. Allison, Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), especially chapters 4 and 3. In more detail, Protestants gratefully use tradition (not Tradition, as in the Catholic sense), or wisdom from the past, as a servant to help their churches engage in the proper understanding and application of Scripture and the formulation of sound doctrine. 4. This attribute does not mean that people have to possess a written copy of Scripture and be able to read it. Rather, in the case of the majority of people today in whose language Scripture has yet to be translated and/or if those people are illiterate, they only need to be able to understand oral communication. Scripture read and heard is God’s necessary Word for them.

Zacharias Ursinus | Caspar Olevianus (Heidelberg Catechism)

Zacharias Ursinus (1534-1583), a sixteenth century German theologian, born Zacharias Baer in Breslau (now Wroc?aw, Poland). Like all young scholars of that era he gave himself a Latin name from ursus, meaning bear. He is best known as a professor of theology at the University of Heidelberg and co-author with Caspar Olevianus (1536-1587) of the Heidelberg Catechism…. (THEOPEDIA)

The Heidelberg Catechism is a document used in Reformed churches to help teach church doctrine. It takes the form of a series of questions and answers to help the reader better understand the material. It has been translated into many languages and is regarded as the most influential Reformed catechism.

Elector Frederick III, sovereign of the Palatinate from 1559 to 1576, appointed Zacharias Ursinus and Caspar Olevianus, to write a Reformed catechism based on input from the leading Reformed scholars of the time. One of its aims was to counteract the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church regarding theology, basing each statement on the text of the Bible…… (THEOPEDIA)

The Insanity of Luther (R. C. Sproul)

R. C. Sproul’s popular lecture on Protestant Reformer Martin Luther.

Luther’s Dialectics (Two Kingdoms) |Updated|

“[T]he paradox is that God must destroy in us, all illusions of

righteousness before he can make us righteous…”

~ Martin Luther

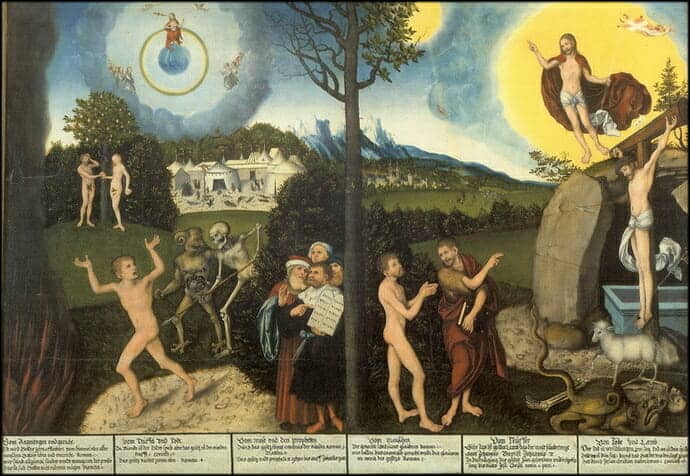

(Click To Enlarge – More About This Painting Below)

Luther LOVED Paul’s letter to the Romans. In this letter we find a battle of this “two-kingdom” idea (7:14-25[a]), which surely made him meditate on these things listed below.

A WILDERNESS OF CASUISTRY

In 1957, the great Reformation historian Johannes Heckel called Luther’s two-kingdoms theory a veritable Irrgarten, literally “garden of errors,” where the wheats and tares of interpretation had grown indiscriminately together. Some half a century of scholarship later, Heckel’s little garden of errors has become a whole wilderness of confusion, with many thorny thickets of casuistry to ensnare the unsuspecting. It is tempting to find another way into Lutheran contributions to legal theory. But Luther’s two-kingdoms theory was the framework on which both he and many of his followers built their enduring views of law and authority, justice and equity, society and politics. We must wander in this wilderness at least long enough to get our legal bearings.

Luther was a master of the dialectic — of holding two doctrinal opposites in tension and of exploring ingeniously the intellectual power of this tension. Many of his favorite dialectics were set out in the Bible and well rehearsed in the Christian tradition: spirit and flesh, soul and body, faith and works, heaven and hell, grace and nature, the kingdom of God versus the kingdom of Satan, the things that are God’s and the things that are Caesar’s, and more. Some of the dialectics were more uniquely Lutheran in accent: Law and Gospel, sinner and saint, servant and lord, inner man and outer man, passive justice and active justice, alien righteousness and proper righteousness, civil uses and theological uses of the law, among others.

Luther developed a good number of these dialectical doctrines separately in his writings from 1515 to 1545 — at different paces, in varying levels of detail, and with uneven attention to how one doctrine fit with others. He and his followers eventually jostled together several doctrines under the broad umbrella of the two-kingdoms theory. This theory came to describe at once: (1) the distinctions between the fallen realm and the redeemed realm, the City of Man and the City of God, the Reign of the Devil and the Reign of Christ; (2) the distinctions between the sinner and the saint, the flesh and the spirit, the inner man and the outer man; (3) the distinctions between the visible Church and the invisible Church, the Church as governed by civil law and the Church as governed by the Holy Spirit; (4) the distinctions between reason and faith, natural knowledge and spiritual knowledge; and (5) the distinctions between two kinds of righteousness, two kinds of justice, two uses of law.

When Luther, and especially his followers, used the two-kingdoms terminology, they often had one or two of these distinctions primarily in mind, sometimes without clearly specifying which. Rarely did all of these distinctions come in for a fully differentiated and systematic discussion and application, especially when the jurists later invoked the two-kingdoms theory as part of their jurisprudential reflections. The matter was complicated even further because both Anabaptists and Calvinists of the day eventually adopted and adapted the language of the two kingdoms as well — each with their own confessional accents and legal applications that were sometimes in sharp tension with Luther’s and other Evangelical views. It is thus worth spelling out Luther’s understanding of the two kingdoms in some detail, and then drawing out its implications for law, society, and politics.

John Witte, Jr., Law and Protestantism: The Legal Teachings of the Lutheran Reformation (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2002) ,94-95.

More about the painting. Be aware that the text below may be imperfect as it was “Google Translated” ~ via WIKI

- ARTIST: Lucas Cranach Starszy (1472–1553)

- NAME of PAINTING: Cranach Law and Grace Gotha

According to the letters of the Apostle Paul, man’s way out of condemnation, sin and law is presented to eternal life, faith and grace. Since for Martin Luther sin is inextricably linked to the human being, the believer of the Mosaic law needs to be aware of his sinfulness. He must realize that he will fail and despair of the commandments of the punishing Old Testament God. This despair is the prerequisite for salvation through Christ and the Gospel. According to the differentiation made by Luther, the tree in the center of the image separates the contrasted events from the Old and New Testaments. In the left half of the law, the tree of life is dried, on the right side of the gospel it bears greening branches. On the left, death and the devil chase the sinful man into hellish fire while looking to the right to Moses, who points to the tablets of the Ten Commandments in a group of prophets of the Old Testament. Representations of the sin and the Last Judgment in the wide landscape show the origin and punishment of human misconduct. The scene of the bronze serpent from the Old Testament, which is important to Luther, typologically points to the crucifixion and shows the salvation of the Israelites before the poison by following the direction of God.

Right on the right of the tree, John the Baptist can be seen along with the naked man on the left. John, as the last prophet before Christ, stands for Luther between the law and the gospel, which is why he has the role of mediator. He directs the attention of the naked, who stands completely calmly and with folded hands, to the Crucified at the right edge of the picture. From the side-wound of Christ is a stream of blood, which extends over nearly the whole width of the right half, and goes down on the breast of the naked. The dove of the Holy Spirit appears in the stream of blood. It is shown here that only Christ, who died vicariously for man and whose good news is transmitted by the Holy Spirit, can abolish the sentence by the law. Only by his faith, sola fide, does the man of divine forgiveness participate in the form of the delivering blood-stream. By the risen Christ, who rises above the grave-cave behind the cross, the dead and the devil who pursued the sinner on the left side are banned: both lie conquered before the cross, under the Lamb of God, like the Risen One The victory flag. The sinner of the law is, however, a righteous one, with which the Gotha image illustrates the aspect of simul iustus et peccator. At the gates of Bethlehem, in the background of the right, the Annunciation appears to the shepherds. Like the raising of the brazen serpent, which the eye of the beholder finds right on the other side of the tree, this scene shows the recognition of God’s Word by man. For the viewer, it is made clear that the law and the gospel proclaim the same joyous message which always leads to Christ. Quotations from the Old and New Testaments in the lower part of the table underline the statement and also provide the biblical legitimation of the representation.

John Calvin & Ulrich Zwingli | The Drowning of the Anabaptists

Martin Luther: The Wild Boar |Erwin Lutzer|

John Hus: The Goose Who Became a Swan |Erwin Lutzer|

Religious Wars | Huguenots v. Catholics (1562-1598)

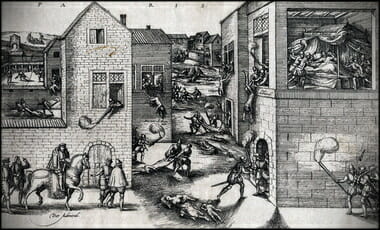

Preparation for the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (During the Fourth War, 1868) ~ Painting by Kārlis Hūns

See more on “war,” here:

- Causes of Wars;

- The Spanish Inquisition Was Bad, and Yes, Mostly Secular;

- The Crusades vs. The Three Caliphates (Moral Equivalence).

Couple things to keep in mind as you read. Firstly, while this is an example of a “religious war, most wars are not:

(CAUSES OF WARS) A recent comprehensive compilation of the history of human warfare, Encyclopedia of Wars by Charles Phillips and Alan Axelrod documents 1763 wars, of which 123 have been classified to involve a religious conflict. So, what atheists have considered to be ‘most’ really amounts to less than 7% of all wars. It is interesting to note that 66 of these wars (more than 50%) involved Islam, which did not even exist as a religion for the first 3,000 years of recorded human warfare. Even the Seven Years’ War, widely recognized to be “religious” in motivation, noting that the warring factions were not necessarily split along confessional lines as much as along secular interests. Even the Seven Years’ War, widely recognized to be “religious” in motivation, noting that the warring factions were not necessarily split along confessional lines as much as along secular interests. And the Thirty Years’ War cannot be viewed as “religious” in that you should find certain aspects if this were the case….

[….]

(STAND TO REASON) Not only were students able to demonstrate the paucity of evidence for this claim, but we helped them discover that the facts of history show the opposite: religion is the cause of a very small minority of wars. Phillips and Axelrod’s three-volumeEncyclopedia of Wars lays out the simple facts. In 5 millennia worth of wars—1,763 total—only 123 (or about 7%) were religious in nature (according to author Vox Day in the book The Irrational Atheist). If you remove the 66 wars waged in the name of Islam, it cuts the number down to a little more than 3%. A second [6-volume] scholarly source, The Encyclopedia of War edited by Gordon Martel, confirms this data, concluding that only 6% of the wars listed in its pages can be labelled religious wars. Thirdly, William Cavanaugh’s book, The Myth of Religious Violence, exposes the “wars of religion” claim. And finally, a recent report (2014) from the Institute for Economics and Peace further debunks this myth.

- Alan Axelrod & Charles Phillips, Encyclopedia of Wars, 3 volumes (New York, NY: Facts on File, 2005);

- The General History of the Late War (Volume 3); Containing It’s Rise, Progress, and Event, in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America (No Publisher [see here], date of publication was from about 1765-1766), 110;

- William T. Cavanaugh, The Myth of Religious Violence (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Gordon Martel, The Encyclopedia of War, 5 Volumes (New Jersey, NJ: Wiley, 2012).

The other thing to keep in mind, “religious wars” is often over-used by atheists… one honest atheist notes the following:

Atheists often claim that religion fuels aggressive wars, both because it exacerbates antagonisms between opponents and also because it gives aggressors confidence by making them feel as if they have God on their side. Lots of wars certainly look as if they are motivated by religion. Just think about conflicts in Northern Ireland, the Middle East, the Balkans, the Asian subcontinent, Indonesia, and various parts of Africa. However, none of these wars is exclusively religious. They always involve political, economic, and ethnic disputes as well. That makes it hard to specify how much [of a] role, if any, religion itself had in causing any particular war. Defenders of religion argue that religious language is misused to justify what warmongers wanted to do independently of religion. This hypothesis might seem implausible to some, but it is hard to refute, partly because we do not have enough data points, and there is so much variation among wars.

- Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Morality Without God? (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009), 33-34.

And just before getting to the larger excerpt, maybe a small primer about this event is in order via CHRISTIANITY.COM (see more at CHRISTIANITY TODAY):

In France, following the Reformation, Calvinists known as Huguenots sprang up in large numbers. The Roman Catholic establishment persecuted them. Manipulated by French political leaders, the Huguenots rose to defend their rights. Their behavior and methods in turn outraged Catholics. War ravaged France. Although fewer in numbers than their foes, the Huguenots fought so fiercely they managed to extract concessions which allowed them to build churches and manage affairs in cities where they had majorities. But the bloodshed imprinted lasting animosity between Protestants and the Catholic majority.

Out of this smoldering hatred flared up one of the most regrettable events of church history. On August 22, 1572 an attempt was made in Paris to assassinate Huguenot leader and French patriot Coligny. Wounded, he returned home to recover. Accounts disagree as to what happened next and who was responsible. Late on this day, August 23, 1572, armed men, led by the Guises, broke into Coligny’s apartment, overcame the fierce resistance of his guards and killed him. Coligny’s death was the signal for a general butchery of the Huguenots. This atrocity is known to history as the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre because it lasted well into that saint’s day.

Catholics slaughtered Huguenots in cold blood into the morning of the 24th in Paris and for days in outlying regions. As many as 70,000 perished. The rest fled to fortified cities and fought back. Their movement became known as La Cause (The Cause) and pitted them against The Holy League (La Sainte Ligue). Brutal fighting raged across the French kingdom.

Charles IX publicly claimed he had ordered the massacre. Certainly the Paris constabulary were warned in advance to prepare for disturbances. Many historians have seen the plot as the work of Catherine de Medici, who felt her power threatened. Possibly Charles, by taking credit, was trying to reap a political benefit from the gruesome event. If so, he won no plaudits outside Catholic regions. Pope Gregory XIII struck a special medallion to commemorate the “holy” act but most other European reaction was horrified. Charles himself suffered psychological agonies from the affair.

The Massacre of St. Bartholomew was not the end of the matter. When the Protestant Henry of Navarre converted to Catholicism in order to become king, he granted his Huguenot compatriots a number of rights under the Edict of Nantes. These rights were gradually eroded, more Huguenot revolts occurred and, finally, 400,000 fled the country into voluntary exile under Louis XIV.

These people were part of the influence (among others) in early America and Canada:

- Following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, there occurred the greatest migration of peoples in the history of the world. More than 600,000 went to Holland, Belgique, England, Ireland, Austria, Russia, South and North America. The largest numbers came to Canada and the American Colonies; and of this number, the largest came to New England and New Netherlands. (HISTORY BOX)

Here is an excerpt from the Encyclopedia of War on the “Religious War” #’s 1-9:

- Alan Axelrod & Charles Phillips, Encyclopedia of Wars, Vol II (New York, NY: Facts On File, 2005), 931-936.

Huguenots Fight To Survive

On March 1, 1562, supporters of the Catholic duke Francois de Guise (1519-63) killed a congregation of Protestants at Vassy. This massacre was instigated by the granting of limited toleration to the Protestants by Catherine de’ Medici (1519-85), the queen mother who took control of the throne at the death of King Francis II (154460). The Catholics, under Francois de Guise, the Constable de Montmorency (Anne, duc de Montmorency; 14931567), and Prince Antoine de Bourbon (1518-62), king of Navarre, and the Protestants, under Louis I de Bourbon, prince of Conde (1530-69), and Comte Gaspard de Col-igny (1519-72), admiral of France, were soon pitted against each other in a battle known as the First War of Religion. Louis de Conde and Gaspard de Coligny ordered the Huguenots to seize Orleans to retaliate for the Vassy massacre and called on all Protestants in France to rebel. In September 1562, the English sent John Dudley (fl. 16th century) of Warwick to help the Huguenots, and his force captured Le Havre. About one month later, the Catholics defeated Rouen, a Protestant stronghold. One of the leaders of the Catholic movement, Antoine de Bourbon, was killed during the attack. The Huguenots continued to rise in rebellion, and in December 15,000 Protestants under Conde and Coligny marched north to join the English troops at Le Havre. En route, they encountered about 19,000 Catholics at Dreux. The Catholics under Guise were victorious, but one of their leaders, Montmorency, was captured, as was the Protestant leader Conde. On February 18, 1563, Guise was killed while besieging Orleans. Peace was finally secured in March when Montmorency and Conde, both prisoners since the Battle of Dreux, negotiated a settlement at the request of Queen. Catherine. The Peace of Amboise stipulated a degree of tolerance. The opposing sides then combined forces to push the English from Le Havre, which fell on July 28, 1563.

On March 1, 1562, supporters of the Catholic duke Francois de Guise (1519-63) killed a congregation of Protestants at Vassy. This massacre was instigated by the granting of limited toleration to the Protestants by Catherine de’ Medici (1519-85), the queen mother who took control of the throne at the death of King Francis II (154460). The Catholics, under Francois de Guise, the Constable de Montmorency (Anne, duc de Montmorency; 14931567), and Prince Antoine de Bourbon (1518-62), king of Navarre, and the Protestants, under Louis I de Bourbon, prince of Conde (1530-69), and Comte Gaspard de Col-igny (1519-72), admiral of France, were soon pitted against each other in a battle known as the First War of Religion. Louis de Conde and Gaspard de Coligny ordered the Huguenots to seize Orleans to retaliate for the Vassy massacre and called on all Protestants in France to rebel. In September 1562, the English sent John Dudley (fl. 16th century) of Warwick to help the Huguenots, and his force captured Le Havre. About one month later, the Catholics defeated Rouen, a Protestant stronghold. One of the leaders of the Catholic movement, Antoine de Bourbon, was killed during the attack. The Huguenots continued to rise in rebellion, and in December 15,000 Protestants under Conde and Coligny marched north to join the English troops at Le Havre. En route, they encountered about 19,000 Catholics at Dreux. The Catholics under Guise were victorious, but one of their leaders, Montmorency, was captured, as was the Protestant leader Conde. On February 18, 1563, Guise was killed while besieging Orleans. Peace was finally secured in March when Montmorency and Conde, both prisoners since the Battle of Dreux, negotiated a settlement at the request of Queen. Catherine. The Peace of Amboise stipulated a degree of tolerance. The opposing sides then combined forces to push the English from Le Havre, which fell on July 28, 1563.

The Peace of Amboise (July 28, 1563), which stipulated a greater degree of tolerance between the Catholics and the Huguenots in France, ended the First WAR OF RELIGION. However, peace lasted only four years. On September 29, 1567, the Huguenots under Louis de Bourbon, prince de Conde (1530-69), and Comte Gaspard de Coligny (1519-72) tried to capture the royal family at Meaux. Although they were unsuccessful, other Protestant bands threatened Paris and captured Orleans, Assent, Vienne, Valence, Nimes, Montpellier, and Montaubon. At the Battle of St. Denis, a force of 16,000 men under Constable de Montmorency (Anne, duc de Montmorency; 1493-1567), attacked Conde’s small army of 3,500. Despite the long odds, the Huguenots managed to remain on the field for several hours. Montmorency, aged 74, was killed during the fray. This war ended on March 23, 1568, with the Peace of Longjumeau by which the Huguenots gained substantial concessions from Queen Catherine de’ Medici (1519-85).

The Peace of Amboise (July 28, 1563), which stipulated a greater degree of tolerance between the Catholics and the Huguenots in France, ended the First WAR OF RELIGION. However, peace lasted only four years. On September 29, 1567, the Huguenots under Louis de Bourbon, prince de Conde (1530-69), and Comte Gaspard de Coligny (1519-72) tried to capture the royal family at Meaux. Although they were unsuccessful, other Protestant bands threatened Paris and captured Orleans, Assent, Vienne, Valence, Nimes, Montpellier, and Montaubon. At the Battle of St. Denis, a force of 16,000 men under Constable de Montmorency (Anne, duc de Montmorency; 1493-1567), attacked Conde’s small army of 3,500. Despite the long odds, the Huguenots managed to remain on the field for several hours. Montmorency, aged 74, was killed during the fray. This war ended on March 23, 1568, with the Peace of Longjumeau by which the Huguenots gained substantial concessions from Queen Catherine de’ Medici (1519-85).

The Third War of Religion broke out on August 18, 1568, when Catholics attempted to capture Louis de Bourbon, prince de Conde (1530-69), and Comte Gaspard de Coligny (1519-72), the primary Protestant leaders. The Royalist Catholics continued to suppress Protestantism. Sporadic fighting occurred throughout the Loire Valley for the remainder of 1568. In March 1569, the Royalists under Marshal Gaspard de Tavannes (1509-73) engaged in battle with Condes forces in the region between Angouleme and Cognac. Later in March, Tavanne crossed the Charente River near Chateauneuf and soundly defeated the Huguenots at the Battle of Jarmac. Although Conde was captured and murdered, Coligny managed to withdraw a portion of the Protestant army in good order. About three months later, help for the Huguenots arrived in the form of 13,000 German Protestant reinforcements. This enlarged force laid siege to Poitiers. Then on August 24, 1569, Col-igny sent Comte Gabriel de Montgomery (c. 1530-74) to Orthez, where he repulsed a Royalist invasion of French-held Navarre and defeated Catholic forces arranged against him. Royalist marshal Tavanne then relieved Poitiers and forced Coligny to raise the siege. The major battle of the Third War of Religion occurred on October 3, 1569, at Moncontour. The Royalists, aided by a force of Swiss sympathizers, forced the Huguenot cavalry off the field and then crushed the Huguenot infantry. The Huguenots lost about 8,000, whereas Royalist losses numbered about 1,000. The following year, however, Coligny marched his Huguenot forces through central France from April through June and began threatening Paris. These actions forced the Peace of St. Germain, which granted many religious freedoms to the Protestants.

The Third War of Religion broke out on August 18, 1568, when Catholics attempted to capture Louis de Bourbon, prince de Conde (1530-69), and Comte Gaspard de Coligny (1519-72), the primary Protestant leaders. The Royalist Catholics continued to suppress Protestantism. Sporadic fighting occurred throughout the Loire Valley for the remainder of 1568. In March 1569, the Royalists under Marshal Gaspard de Tavannes (1509-73) engaged in battle with Condes forces in the region between Angouleme and Cognac. Later in March, Tavanne crossed the Charente River near Chateauneuf and soundly defeated the Huguenots at the Battle of Jarmac. Although Conde was captured and murdered, Coligny managed to withdraw a portion of the Protestant army in good order. About three months later, help for the Huguenots arrived in the form of 13,000 German Protestant reinforcements. This enlarged force laid siege to Poitiers. Then on August 24, 1569, Col-igny sent Comte Gabriel de Montgomery (c. 1530-74) to Orthez, where he repulsed a Royalist invasion of French-held Navarre and defeated Catholic forces arranged against him. Royalist marshal Tavanne then relieved Poitiers and forced Coligny to raise the siege. The major battle of the Third War of Religion occurred on October 3, 1569, at Moncontour. The Royalists, aided by a force of Swiss sympathizers, forced the Huguenot cavalry off the field and then crushed the Huguenot infantry. The Huguenots lost about 8,000, whereas Royalist losses numbered about 1,000. The following year, however, Coligny marched his Huguenot forces through central France from April through June and began threatening Paris. These actions forced the Peace of St. Germain, which granted many religious freedoms to the Protestants.

A massacre of 3,000 Protestants and their leader Louis de Bourbon, prince of Conde (1530-69), precipitated the outbreak of the Fourth War of Religion between Catholics and Protestants in France. After the massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Eve in Paris, August 24, 1572, Prince Henry IV of Navarre (1553-1610) took charge of the Protestant forces. Marked primarily by a long siege of La Rochelle by Royalist forces under another Prince Henry, the younger brother of Charles IX (1550-74), this Fourth War of Religion resulted in the Protestants’ gaining military control over most of southwest France. However, at least 3,000 more Huguenots were massacred in the provinces before the war ended.

A massacre of 3,000 Protestants and their leader Louis de Bourbon, prince of Conde (1530-69), precipitated the outbreak of the Fourth War of Religion between Catholics and Protestants in France. After the massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Eve in Paris, August 24, 1572, Prince Henry IV of Navarre (1553-1610) took charge of the Protestant forces. Marked primarily by a long siege of La Rochelle by Royalist forces under another Prince Henry, the younger brother of Charles IX (1550-74), this Fourth War of Religion resulted in the Protestants’ gaining military control over most of southwest France. However, at least 3,000 more Huguenots were massacred in the provinces before the war ended.

The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre outraged even Catholic moderates, who, seeking to counter the extremes of the Catholic Royalists, formed a new political party, the Politiques, to negotiate with the Protestants and establish peace and national unity.

Protestants and Catholics in France had been fighting sporadically since 1562 in the First War of RELIGION, the Second War of RELIGION, the Third War of RELIGION, and the Fourth War of RELIGION when violence again erupted in 1575. In the most important action of this war, Henry, duc de Guise (1555-88), led the Catholic Royalists to victory at the Battle of Dorman. Aligned against Guise, however, were not only the Protestants under Henry IV of Navarre (1553-1610) but also the Politiques, moderate Catholics who wanted the king to make peace with the Protestants and restore national unity. Henry III (1551-89) was not wholeheartedly in support of Guise, and he offered pledges of more religious freedom to the Protestants at the Peace of Mousieur, signed on May 5,1576. Guise refused to accept the terms of the peace and began negotiating with Philip II (1527-98) of Spain to organize a Holy League and secure Spain’s help in capturing the French throne.

Protestants and Catholics in France had been fighting sporadically since 1562 in the First War of RELIGION, the Second War of RELIGION, the Third War of RELIGION, and the Fourth War of RELIGION when violence again erupted in 1575. In the most important action of this war, Henry, duc de Guise (1555-88), led the Catholic Royalists to victory at the Battle of Dorman. Aligned against Guise, however, were not only the Protestants under Henry IV of Navarre (1553-1610) but also the Politiques, moderate Catholics who wanted the king to make peace with the Protestants and restore national unity. Henry III (1551-89) was not wholeheartedly in support of Guise, and he offered pledges of more religious freedom to the Protestants at the Peace of Mousieur, signed on May 5,1576. Guise refused to accept the terms of the peace and began negotiating with Philip II (1527-98) of Spain to organize a Holy League and secure Spain’s help in capturing the French throne.

The Sixth War of Religion between the Catholics and Protestants in France included only one campaign and was settled by the Peace of Bergerac of 1577. During this period, Henry III (1551-89) tried to persuade the Holy League, formed in 1576 by Catholic leader Henry, duke de Guise (1555-88), and Philip II (1527-98) of Spain, to support an attack on the Protestants. Henry succeeded in subduing the Protestants but wavered in his determination to carry out the terms of the Peace of Bergerac.

The Sixth War of Religion between the Catholics and Protestants in France included only one campaign and was settled by the Peace of Bergerac of 1577. During this period, Henry III (1551-89) tried to persuade the Holy League, formed in 1576 by Catholic leader Henry, duke de Guise (1555-88), and Philip II (1527-98) of Spain, to support an attack on the Protestants. Henry succeeded in subduing the Protestants but wavered in his determination to carry out the terms of the Peace of Bergerac.

[….]

The Seventh War of Religion in 1580, also known as the “Lovers’ War,” had little to do with hostilities between the Catholics and Protestants. Instead fighting was instigated by the actions of Margaret, the promiscuous wife of Henry IV of Navarre (1553-1610). Over the next five years, Catholics, Protestants, and the moderate Politiques (see RELIGION, FOURTH WAR OF; RELIGION, FIFTH WAR OF) all engaged in intrigue in their attempts to name a successor to the childless Henry III. Although Henry of Navarre was next in line by direct heredity, the Holy League maneuvered to ensure that Henry, duc de Guise, would gain the throne after the reign of Charles de Bourbon (1566-1612), proposed as the successor to Henry III.

Battle of Coutas (October 20th, 1587 ~ During the Eight War)

The Eighth War of Religion, also known as the “War of the Three Henrys,” pitted the Royalist Henry III (1551-89), Henry of Navarre (1553-1610), and Henry de Guise (1555-88) against each other in a struggle over succession to the French throne. The war began when Henry III withdrew many of the concessions he had granted to the Protestants during his reign. At the Battle of Coutras on October 20, 1587, the army of Henry of Navarre, 1,500 cavalry and 5,000 infantry, smashed the Royalist cavalry-1,700 lancers—and 7,000 infantry. More than 3,000 Royalists were killed; Protestant deaths totaled 200. Especially effective against the Royalist was the massed fire of the Protestant arquebuses, primitive muskets.

The Eighth War of Religion, also known as the “War of the Three Henrys,” pitted the Royalist Henry III (1551-89), Henry of Navarre (1553-1610), and Henry de Guise (1555-88) against each other in a struggle over succession to the French throne. The war began when Henry III withdrew many of the concessions he had granted to the Protestants during his reign. At the Battle of Coutras on October 20, 1587, the army of Henry of Navarre, 1,500 cavalry and 5,000 infantry, smashed the Royalist cavalry-1,700 lancers—and 7,000 infantry. More than 3,000 Royalists were killed; Protestant deaths totaled 200. Especially effective against the Royalist was the massed fire of the Protestant arquebuses, primitive muskets.

Despite the Protestant victory at Coutras, the Catholics under Henry of Guise prevailed at Vimoy and Auneau and checked the advance of a German army marching into the Loire Valley to aid to Protestants. Henry’s next victory was in Paris, where he forced the king to capitulate in May 1588. In subsequent intrigues, Henry de Guise and his brother Cardinal Louis I de Guise (1527-78) were assassinated. Fleeing the Catholics’ rage over the murders, Henry Ill sought refuge with Protestant leader Henry of Navarre. The king failed to find permanent safety and was assassinated, stabbed to death, by a Catholic monk on August 2, 1589. On his deathbed, the king named Henry of Navarre his successor. The Catholics refused to acknowledge him king, insisting instead that Cardinal Charles de Bourbon (1566-1612) was the rightful ruler of France. This conflict sparked the NINTH WAR OF RELIGION.

The naming of Henry of Navarre (1553-1610) as successor to the French throne sparked the final War of Religion between Protestant Huguenots and Catholics in France. Insisting that Charles, duke de Bourbon (1566-1612), was the rightful successor to Henry III (1551-89), the Catholics enlisted the aid of the Spanish. Charles, duke of Mayenne (1554-1611), the younger brother of Henry of Guise (1555-88), led the Catholic efforts.

The naming of Henry of Navarre (1553-1610) as successor to the French throne sparked the final War of Religion between Protestant Huguenots and Catholics in France. Insisting that Charles, duke de Bourbon (1566-1612), was the rightful successor to Henry III (1551-89), the Catholics enlisted the aid of the Spanish. Charles, duke of Mayenne (1554-1611), the younger brother of Henry of Guise (1555-88), led the Catholic efforts.

At the Battle of Argues on September 21,1589, Henry of Navarre (1553-1660) ambushed Mayenne’s army of 24,000 French Catholic and Spanish soldiers. Having lost 600 men, Mayenne withdrew to Amiens, while the victorious Navarre, whose casualties numbered 200 killed or wounded, rushed toward Paris.

A Catholic garrison near Paris repulsed Navarre’s advance on November 1, 1589. Not to be daunted in his quest for the throne, Henry withdrew but promptly proclaimed himself Henry IV and established a temporary capital at Tours.

Henry of Navarre won another important battle at Ivry on March 14, matching 11,000 troops against Mayenne’s 19,000. Mayenne lost 3,800 killed, whereas Navarre suffered only 500 casualties.

Civil war continued unabated. Between May and August 1590, Paris was reduced to near starvation during Navarre’s siege of the city. Maneuvers continued, especially in northern France until May 1592; however, in July 1593 Henry of Navarre reunited most of the French populace by declaring his return to the Catholic faith. His army then turned to counter a threat of invasion by Spain and the French Catholics allied with Mayenne.

On March 21, 1594, Henry of Navarre entered Paris in triumph and over the next few years battled the invading Spanish: at Fontaine-Francaise on June 9, 1596, at Calais on April 9, 1596, and at Amiens on September 17, 1596. No further major campaigns ensued.

On April 13, 1598, Henry of Navarre ended the decades of violence between the Catholics and the Protestants by issuing the Edict of Nantes, whereby he granted religious freedom to the Protestants. Then on May 2, 1598, the war with Spain ended with the Treaty of Vervins, whereby Spain recognized Henry as king of France. The next major conflict between the Catholics and Protestants in France occurred 27 years later when the Protestants rose in revolt in 1625 and the English joined their cause in the ANGLO-FRENCH WAR (1627-1628).

➤ Further reading: R. J. Knecht, The French Civil Wars, 1562-1598 (New York: Pearson Education, 2000); R. J. Knecht and Mabel Segun, French Wars of Religion (New York: Addison-Wesley Longman, 1996).

- 2 of 3

- « Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next »