THE “DUMBING DOWN” DRUG GROWS STRONGER

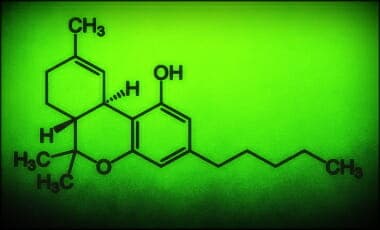

How marijuana became such a public health concern starts with the economic pressures felt by the drug’s growers to increase the potency of marijuana in order to raise prices—and therefore prof-its—from its sale. By constantly experimenting with breeding practices and cultivation techniques over several decades, producers and growers steadily made progress in greatly elevating the levels of THC (the psychoactive ingredient) found in the oily resin of the marijuana plant’s leaves and flowers.

At the University of Mississippi, a potency-monitoring project has been under way for the past few decades, measuring the concentration of THC in thousands of marijuana samples randomly selected from law-enforcement seizures. Since 1983, when THC concentrations averaged below 4 percent, potency has intensified until it now exceeds an average of 10 percent. Many marijuana samples are in the 10-20 percent range. Some marijuana samples show THC concentrations exceeding 30 percent. If we were talking about alcohol, this increase in intoxication potential would be like going from drinking a “lite” beer a day to consuming a dozen shots of vodka.

One obvious direct result of this intensified marijuana potency has been an even greater corresponding escalation in emergency room admissions for marijuana-related reactions. The nationwide total went from an estimated 16,251 emergency room visits in the United States related to marijuana use in 1991, to exceeding 374,000 emergency room admissions in 2008—a nearly twenty-five-fold increase in just seventeen years.

Interestingly, the number of users of marijuana stayed about the same during this period—suggesting that the increase in ER visits did not have to do simply with increased numbers of users. These reactions ranged from anxiety and panic attacks, paranoia, and psychotic symptoms, to respiratory and cardiovascular distress. An analysis of two large national surveys of marijuana addiction found that “more adults in the United States had a marijuana use disorder in 2001-2002 than in 1991-1992,” with the highest rates among young black men and women, and young Hispanic men, even though use rates were the same for the two ranges of years studied.

Today’s typical marijuana sample contains up to five-hundred chemical constituents. About seventy of these chemicals are known as cannabinoids, and one of them—THC—is psychoactive.

Human brains contain a system of cannabinoid receptors, sort of like a bleacher full of open baseball mitts available to receive pitched baseballs in the form of cannabinoid molecules. The highest concentration of these receptors is in those parts of the brain that affect thinking, memory, concentration, sensory and time perception, and the coordination of body movements.

Once these brain receptors have been triggered by marijuana’s cannabinoids, which effectively begin to mimic and then hijack some brain neurotransmitters, the resulting intoxication distorts the brain’s natural chemical balance and produces distortions in thinking, problem-solving, memory, and learning, along with impaired coordination and perceptual abilities.

[….]

MORE SERIOUS CONSEQUENCES FOR KIDS

As children’s brain development is disrupted by chronic marijuana use, their risk for dependency accelerates. And given the ever-increasing potency, marijuana becomes an expensive public health hazard with long-lasting effects.

We can measure the impact on life development from marijuana use and its alterations of brain function in several different ways. Research shows that adolescents who smoke marijuana every weekend over a two-year period are nearly six times more likely to drop out of school than nonsmokers, more than three times less likely to enter college than nonsmokers, and more than four times less likely to earn a college degree. We don’t know whether marijuana causes adolescents to drop out of school or not, but given marijuana’s effect on learning and motivation, it is safe to say that marijuana use very likely has something to do with it.

Stunted emotional development is also strongly associated with adolescent marijuana use. Females show a greater vulnerability than males to this heightened risk of anxiety attacks and depression.

A 2002 study in the British Medical Journal, for instance, described how researchers in Australia studied 1,601 students aged fourteen to fifteen over a seven-year period; 60 percent had used marijuana by twenty years of age. The conclusions reached by the authors should give all parents cause for concern. They wrote: “Daily use in young women was associated with an over fivefold increase in the odds of reporting a state of depression and anxiety…weekly or more frequent cannabis use in teenagers predicted an approximately twofold increase in risk for later depression and anxiety.”

In order to assess a young person’s ability to perceive, understand, and manage their emotions while under the influence of marijuana, a team of researchers in 2006 used a sophisticated mood-testing scale to measure emotional responses in 133 college students (114 women and 19 men) with an average age of twenty-one years. Those who had started consuming marijuana at earlier ages were found to have an impaired ability to experience normal emotional responses.

Both subtle and acute changes in emotional and intellectual development occur in young marijuana users because the arc of their brain’s structural development becomes recalibrated by marijuana use. Brain researchers documented in 2008 how chronic marijuana use starting in adolescence significantly decreases the size of two brain areas thick in cannabinoid receptors—the amygdala by 7 percent and the hippocampus by 12 percent. One result was that young chronic marijuana users performed much worse than nonusers on verbal learning tests. Heavy marijuana use “exerts harmful effects on brain tissue and mental health,” the authors concluded in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 2008.

Memory impairment poses a serious consequence of chronic or long-term use of marijuana, and these effects can be experienced long after marijuana use is suspended. Three studies in particular make a compelling case that the “dumbing down” effect of marijuana use extends to memory skills.

Difficulties in verbal story memory, along with impairments in learning and working memory for up to six weeks after cessation of marijuana use, were found in a review of studies published in Current Drug Abuse Reviews in 2008. These studies were of both adolescent humans and animals. Though adolescents were more adversely affected by heavy use than adults, adults who began using marijuana in adolescence “showed greater [memory] dysfunction than those who began use later.”

Another 2008 review of the medical literature determined that the evidence points overwhelmingly to “impaired encoding, storage, manipulation, and retrieval mechanisms [in the brains] of longterm or heavy cannabis users.”

One of the pioneering studies on marijuana use and memory appeared in a 2002 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association and helped to set in motion a series of subsequent studies. Nine Australian researchers compared the attention, memory, problem-solving, and verbal-reasoning skills among four groups of individuals: 102 near-daily marijuana users, 51 long-term marijuana users, 51 short-term users, and 33 nonusers who made up the control group. The conclusion: “Long-term heavy cannabis users show impairments in memory and attention that endure beyond the period of intoxication and worsen with increasing years of regular cannabis use.”

But the granddaddy of marijuana and learning studies came out in 2012. and astounded even the most cautious researchers. Scientists, controlling for factors like years of education, schizophrenia, and the use of alcohol or other drugs, followed a cohort of over one thousand people for more than twenty-five years to investigate the effect of cannabis use on IQ. The study found that using marijuana regularly before age eighteen resulted in an average IQ of six to eight fewer points at age thirty-eight relative to those who did not use marijuana before age eighteen. This astounding finding was still true for those teens who used marijuana regularly but stopped using the drug after the age of eighteen. “Our hypothesis is that we see this IQ decline in adolescence because the adolescent brain is still developing, and if you introduce cannabis, it might interrupt these critical developmental processes,” said lead author Madeline Meier, a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University.

“I think this is the cleanest study I’ve ever read” exploring the long-term effects of marijuana use, Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), an arm of the National Institutes of Health, told the Associated Press.

The study was criticized in a paper by economist Dr. Ole Rogeberg of the Ragnar Frisch Centre for Economic Research. Dr. Rogeberg criticized Meier and her team for failing to control for socio-economic status (SES). The paper received wide media coverage. Policy analyst Wayne Hall said that the “Rogeberg study has been presented as though it was a fairly definitive refutation of the Dunedin study [but] his hypothesis has not been confirmed and that’s been lost in the media coverage.”

When Meier and her colleagues had a chance to reexamine their results, their original conclusion was unchanged. They noted that:

“Dr. Rogeberg’s ideas are interesting, but his challenge is based on simulations. We used actual data on 1,037 people to carry out the analyses he suggested. His ideas are not supported by our data….By restricting our analysis to only include children from middle-class homes, our findings of IQ decline in adolescent-onset cannabis users remain unaltered, thereby suggesting that the decline in IQ cannot be attributed to socioeconomic factors alone….Moreover, we note that our results suggesting that adolescent-onset but not adult-onset cannabis users showing IQ decline is consistent with findings in rats, and rats have no schooling or SES.”

A MENTAL ILLNESS LINK

About fifteen years ago, the floodgates started to open on medical research establishing a connection between marijuana use and mental illness. A lot of this research comes from countries outside the United States, such as Sweden, Britain, and New Zealand.

The first strong suggestion that marijuana use can trigger mental problems came in a 1987 study from Sweden published in the British medical journal. Lancet. Researchers did a fifteen-year examination of 45,570 military conscripts and found that those who had used marijuana on more than fifty occasions had a much higher risk—six times higher—of developing schizophrenia relative to nonusers. “Persistence of the association after allowance for other psychiatric illness and social background indicated that cannabis is an independent risk factor for schizophrenia,” concluded the four medical researchers.

Subsequently, evidence from a wide array of studies began to pile up, showing that the more chronic the marijuana use and the earlier in life that marijuana use begins, the greater one’s chances are of developing psychosis typified by delusional thinking and of experiencing the onset of schizophrenia, characterized by a breakdown in thought processes.

To assess the overall findings of these mental health studies from around the world, several systematic reviews of this literature have been performed to weigh the sum total of evidence. For example, a 2007 review in Lancet compared results from thirty-five studies evaluating the impact of marijuana use on the later development of psychosis, which was defined as delusions, hallucinations, or thought disorders. They concluded that marijuana use significantly increased the likelihood of developing psychotic symptoms. There was also a dose-response effect, meaning that the more frequently marijuana was consumed, the more dramatically the risk of developing psychotic symptoms escalated (up to 200 percent for the most frequent users relative to nonusers). The survey authors concluded: “The evidence is consistent with the view that cannabis increases [the] risk of psychotic outcomes.”

An even larger systematic review of studies—called a meta-analysis—was conducted by Australian researchers in 2011, for the Archives of General Psychiatry, using eighty-three studies to assess the impact of marijuana use on the early onset of psychotic illness. The findings were clear and consistent: “The results of meta-analysis provide evidence for a relationship between cannabis use and earlier onset of psychotic illness…. [The] results suggest the need for renewed warnings about the potentially harmful effects of cannabis.”

Another link between marijuana and psychotic symptoms surfaced in research published by a team of eight psychiatrists and researchers in Psychological Medicine in 2010. They discovered that “childhood trauma is associated with both substance [cannabis] misuse and risk for psychosis.” These early childhood traumatizing events can range from physical abuse and sexual molestation, to neglect and abandonment. Psychiatric interviews were initiated with 211 adolescents between the ages of twelve and fifteen to identify both their levels of pot use and any early traumatic events in their lives. The researchers concluded that “the presence of both childhood trauma and early cannabis use significantly increased the risk for psychotic symptoms beyond the risk posed by either risk factor alone, indicating that there was a greater than additive interaction between childhood trauma and cannabis use.”

Still another factor potentially impacting the marijuana and psychosis link is genetic. Several Canadian physicians writing in a 2012 article for Psychiatric Times analyzed the role of certain genes, such as the COMT (Catechol-O-methyltransferase) gene, which have been the subject of numerous studies of psychosis. This particular gene is involved with the metabolism of dopamine in the brain. A variant of this gene slows the breakdown of dopamine which may increase the risk of developing psychosis. Add to this gene variant the use of marijuana, and an even greater risk of psychotic symptoms is observed.

Even if adolescents or teenagers using marijuana don’t become dependent—and the majority don’t—their brains are still modified by the use of marijuana. It’s this modification of brain structure and function that is at the root of mental health problems later in life. As the California Society of Addiction Medicine aptly puts it on their website: “The overwhelming preponderance of scientific evidence provides adequate rationale for public policies that deter, delay and detect child and adolescent marijuana use.”

Kevin A. Sabet, Reefer Sanity: Seven Great Myths About Marijuana (New York, NY: Beaufort Books, 2013), 34-36, 39-46.