If you don’t know about this, there is a bit more at THE DAILY WIRE. But let me say, this is exactly what the Left/Democrats want: division and non-unity. More on this in a sec.

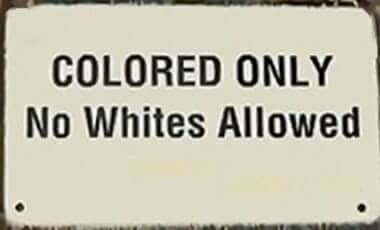

A black family has filed a federal complaint against Mary Lin Elementary (@APSLinRockets) after it was discovered the principal had been segregating the students based on race. Operating on CRT, school believed black kids would do better without whites. pic.twitter.com/0wcbr19UnJ

— Andy Ngô (@MrAndyNgo) August 11, 2021

In this next example from JAMES LINDSEY — and I could offer hundreds — is a jaw dropper (click it to expand the graphic):

Yipes!

It is disturbingly common for American colleges,

public and private, to offer segregated dorms,

graduation ceremonies, and events.

This is unbelievable. Leftist students (and white supremacists) think segregation is just great. Meanwhile, in the decent and civilized world, the rest of us know it isn’t. Thanks for enlightening us, Ami Horowitz.

I think the end of this FIRST THINGS article captures a good portion of the root of the issue….

What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words, by God himself.

Blaise Pascal (Pensees 10.148)

…mans yearning to fill a God shaped vacuum:

…This is, indeed, the collapse of liberalism in race relations, but to understand it we have to dig deeper than racial reasons. Yes, the students spotlight the persistence of racism, they envision a society free of discrimination, and they want more people of color in the professional ranks, all of which are consistent with the liberal outlook of Martin Luther King, Jr. But that only begs the question of why the students’ dissatisfaction now takes a separatist path.

The answer lies in plain sight, but it’s hard to absorb because it gainsays everything higher education has been doing to support historically disadvantaged students. In the hundreds of demand lists, open letters, and petitions that groups have issued since the upheaval at the University of Missouri in fall 2014, the students always single out a heritage of their own that should be passed on by teachers like them. (You can find 80 of these lists here.) College officials take this as a plea for more multiculturalism, more diversity, but that’s not what the students are saying. They’ve seen how multiculturalism works in practice: a token here, a smattering there, this culture and that one, none in a sustained way.

They want something stronger and deeper than that, a more meaningful relationship to the past that will strengthen their identities. Colleges now have “diversity” course requirements that are presumed to evince the respect and “inclusivity” that the officials promised students of color during recruitment times, but the students aren’t impressed. They don’t want to share space with other heritages. They want antecedents that are uniquely theirs, events and art that they can claim as special to them, nobody else. They want their own stories, their own roots. No Melting Pot for them and no Rainbow Coalition, either. Re-segregation is an escape from the old white supremacy and the new diversity as well.

That this apparent regression should be led by the very figures diversity policies were supposed to support must be a shock to college leaders. I’m sure they believe they’re doing all they can, that nobody has more sympathy for the historically disadvantaged than they do. They don’t know what they’ve done wrong, what more they could do to advance diversity and display racial awareness.

In this way, they only reveal the limits of the liberal-diversity outlook. For we should see the motives behind the protests and the calls for re-segregation in universal terms—not racial terms. These students want grounds and foundations, reassuring origins and forebears. They need a solid world and a momentous history and an enchanted reality. This is nothing new, but the need has become acute in the twenty-first century, in good part because liberalism has managed to expel conservatism so thoroughly from the lives of American adolescents. Put yourself in the psyche of the 19-year-old just arrived at college and ask, “What do I have to solidify my fledgling life?”

Chances are that you don’t have religion. You don’t have much patriotism, either, the kind of love that lets you say with pride, “I’m an American!” and gain strength from that loyalty. Moreover, you don’t have an assuring sense of neighborhood, not with the Internet having made so many of your social interactions virtual. Needless to say, the pop culture you enjoy doesn’t align you with any venerable traditions, and the consumerism flooding your iPhone turns you into just that, a consumer.

You have a rootless, floating existence, the only Big Picture being Achievement, Success, Health, Safety. No Gods, no glorious past, no community, no voices of the dead, no thirst for greatness, only a soulless pursuit of degrees and jobs—that’s all college offers.

But “the soul has needs that must be satisfied,” Tocqueville said, and diversity isn’t enough. Students of color in a separatist mindset are but the most overt example of the plight of Generation Z, young Americans entering the world without the support systems they need, urged to be free and independent and self-creating, but in truth, yearning for home and faith and belonging and an inheritance.

A segregated dormitory will give these youths a common experience, a tradition that surrounds them and heartens them. Or at least that’s what they assume. I don’t believe it will work out that way. The ensuing culture of the color-dorm will be just as historically shallow and artistically vulgar as most other youth communities, but it’s the thought that counts. Students of color are telling college leaders, “We don’t want your commiseration—we don’t want your liberalism—we want to be alone.” If this desire is not answered soon, and with something very different than diversity initiatives, the hostility is going to get worse.