Here is the excerpt from Dr. Chapman’s book:

Christianities Advancement vs. Islam’s Stalling

…But what I would argue is that science entered early Christian and medieval Europe by a process of cultural osmosis. For one of the formative and enduring features of Christianity, from the AD 30s and 40s onwards, was its social and cultural flexibility. One did not have to belong to any given racial or cultural group, wear any approved style of clothing, cut one’s beard in a prescribed way, speak a special holy language, or follow essential rituals to be a Christian. Women in particular, amazingly, considering their limited social role in antiquity, were drawn to Christianity in large numbers, as the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles make clear, where they are shown as openly expressing their views. They were even the original witnesses of the resurrection, while St Paul’s first European convert was Lydia of Thyatira, a Greek merchant woman.

In fact Christianity moved into the pre-existing social, legal and administrative structures of Greco-Roman paganism, as Greek civic virtue became infused with Judeo-Christian charity. Roman legal objectivity absorbed key aspects of the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount and the Beatitudes to create a concept of social justice; even the modes of dress of late Roman officials became the vestments of Christian priests; while words like “bishop” and “diocese” derived from classical administrative sources. Christianity, instead of overthrowing the genius of Greece and Rome, simply absorbed its best practical components, and allied them with the teachings of Jesus. The law codes of Christendom, moreover, came to develop non-theological components. The circuit judge system set up by King Henry II in the twelfth century, for instance, might have carried resonances of the assistant judges of Israel appointed by Moses in Exodus, or the judgment towns visited by the prophet Samuel in 1 Samuel, but in practice it administered a new, practical English “Common Law”, and the judges often sat with that innovation of the age, a twelve-man lay jury.

This is how medieval students in Oxford, Paris, Bologna, or Salamanca came to study the pagan philosophies of Plato and Aristotle, the classical Latin poetry of Virgil, and the humane ethics of Cicero along with the Gospels. And very important for the rise of a civil society in which there was an acknowledged saeculum or non-theological exclusivity, the law students at the medieval Inns of Court in London, then as today, learned a pragmatic, case-based evolving civil law that was not especially theological in its foundation. For medieval Christendom was open to non-Christian ideas, provided that they could be reconciled in their broader principles with Christianity.

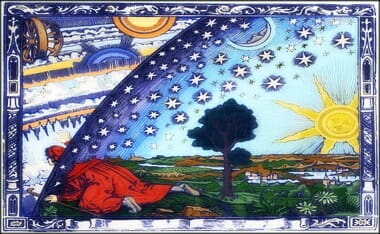

Exactly the same thing happened with science. The astronomy of Ptolemy, the physics of Aristotle, and the medicine of Hippocrates became part of the curriculum in Europe’s great new universities by 1250. Indeed, it was generally accepted that many honest pagans had glimpsed key truths of God’s creation, and who could blame the wise Socrates and Aristotle if they happened to have been born 400 years before Jesus, for their wisdom and honest contributions to learning were beyond question. This is how ancient science came to slide effortlessly into the Christian world, for it was useful for making calendars, treating diseases, and explaining the physical nature of things from the facts then available.

But, you might ask, when talking about science and Christendom, what happened in monotheistic Islam? It is an evident fact of history that, after its initial military conquests in the century after AD 622, Muslim scholars in Baghdad, Cairo, and southern Spain encountered the scientific and medical writings of the Greeks, which they translated into Arabic. And amidst a galaxy of figures such as Ibn Jabir in chemistry, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) in medicine, Ibn Tusi in astronomy, and Al-Haythem (Alhazen) in optics, Arabic science took the Greek scientific tradition further, research-wise, than anyone in Europe over the centuries AD 800-1200. But then, due to a variety of factors embedded within Islamic culture, it stalled and came to a standstill, especially after their last great scientist, the astronomer Ulugh Beigh of Samarkand, was murdered, it was said, by one of his own sons in 1449.

There has been much discussion among scholars as to why Islamic science declined as an intellectual and technical force, and why Christian Europe after 1200 developed a momentum which absorbed — with full acknowledgment — the achievements of the great Muslim scholars and scientists, and accelerated in an unbroken line of development down to the present day. For Islam, just like Judaism and Christianity, is a monotheistic faith, seeing the God of Abraham as the original and only creative force behind the universe. So why did the Islamic monotheistic tradition stall scientifically, while the Judeo-Christian tradition flourished? I think much has to do with a broader receptivity to classical Greco-Roman culture.

As was shown above, Christianity grew directly out of a combination of Judaism and wider Greco-Roman culture. Jesus the man was incarnated as a Jewish rabbi who preached in vernacular Aramaic and could read Hebrew, yet whose teachings, not to mention the commentaries of his disciples, were committed to posterity in Greek and, somewhat later, in Latin. The Jesus of the Gospels, moreover, respected Caesar, the Roman state and its officials; and his disciples even held an election to decide whether Barnabas or Matthias should be co-opted into the Twelve after Judas’s treachery; while St Paul, a Jewish native of the Hellenized “university town” of Tarsus in Cilicia (now Turkey), argued like a Socratic philosopher in his letters and was deeply proud of being a hereditary Roman citizen. Islam, on the other hand, came about in a very different way. The Prophet Mohammed’s roots lay in the essentially tribal society of the seventh-century-AD Arabian peninsula, east of the Red Sea. Tribal custom and not Greco-Roman “civic virtue” moulded its social and cultural practices, and Islam’s lack of a theology of free grace and atonement gave emphasis to an internal legalism that could all too easily generate centuries long sectarian disputes, such as those between the Shi’ites and the Sunnis. And while I fully admit that Christendom has had its own spasms of internal violent reprisal, most recently witnessed in the Troubles in Northern Ireland, I would suggest that Christendom’s classically derived constitutional, negotiated, approach to politics has always provided mechanisms for containment and reconciliation. This has been seen most notably in the active cooperation between the Roman Catholic and Protestant mainstreams, often on an overtly religious level, although splinter groups can remain active until changes in public attitudes eventually render them obsolete.

Islam took from Greco-Roman culture what it found useful in the territories it conquered. These included Greek astronomy, optics, medicine, chemistry, and technology, each of which it amplified and expanded, producing major treatises, often based upon freshly accumulated and carefully classified observational data. Chemistry came to owe an enormous debt to Arabic researchers, as would astronomical, medical, and botanical nomenclature. Indeed, well over a dozen major Arabic works made their way into Europe, where they were translated into Latin, influencing figures like Bishop Robert Grosseteste and Friar Roger Bacon of Oxford, and began to be widely studied in detail in the post-1100 European universities. (On the other hand, I am not aware of the foundational works of European science, such as those of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Vesalius, or Harvey, being translated into Arabic until recent times.) And among other things, that astronomical computing instrument known as the astrolabe, upon which the poet Geoffrey Chaucer wrote the first technical “workshop manual” in the English language around 1381, was a sophisticated Arabic development of a device first outlined by Ptolemy in the second century AD.

Yet while Greek ideas were profoundly formative upon Arabic concepts of the natural world, Islam did not absorb other key ideas of Greek and Roman culture which would become formative to Christian Europe. Greek democratic political ideals, “civic virtue”, and legal monogamy (divorce and mistresses notwithstanding) never became an integral part of Islam as they did of Christendom. Nor did the descent of kingship through holy anointing, which began with Samuel, Saul, and David in 1 Samuel in the Old Testament and entered early Christian kingship practices as the act of coronation, and is still enshrined in the person of HM Queen Elizabeth II.

It is for these reasons, I would argue, that modern science is a child of Judeo-Christian, Greco-Roman parentage, and why I speak of Western science as becoming the dominant style of thinking about the natural world and humanity’s inquisitive relationship with it. Indeed, it is not just about the science and technology, but about the social, intellectual, and cultural assumptions and practices in which modern science is embedded. The very institutions within which science has grown up over the last 900 years, moreover, testify to this inheritance: universities with enduring corporate structures borrowed from Greek and Roman linguistic and civic practice; learned societies — such as the Royal Society of London after 1660 — which were self-electing, self-governing bodies modelled on the “collegiate”, “civic virtue” style Oxford and Cambridge colleges; and rich, free-trading merchant-driven cities such as London, Florence, Venice, Nuremberg, Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg.

As will be shown in more detail in the following chapters, historical Christianity has never been rigidly literalistic in its interpretation of the physical world of Scripture, and it is that very flexibility that has made the faith so versatile and adaptive in its social expression over 2,000 years. A faith that made its first utterance among Aramaic-speaking fishermen and farmers around Galilee (occupying a land surface area no bigger than modern Birmingham), quickly went on to enchant Greek-writing scholars, led to the conversion of the Roman Empire, encompassed people between Mesopotamia, Spain, Britannia, and Ethiopia by AD 600, would inspire the new Latin-speaking universities of Europe by 1200, would engraft onto itself the science, philosophy, legal and social practices of the high classical Mediterranean, would explore possible connections between the teachings of Jesus and the writings of Plato and Virgil, and whose Scriptures would be translated into the vernacular languages of Europe by 1550. Christianity would then go on to inspire the natural theology of the Royal Society Fellows, be the driving force behind the abolition of slavery, supply the moral and spiritual tools that constitute the best and noblest aspects of what we now call “human rights” — and become the prime target for some of the bitterest abuse that many twenty-first-century sceptics feel compelled to heap upon religious belief (and I have heard a good deal of that at first hand!).

Indeed, considering the magnitude of Christianity’s moulding influence upon Western civilization, and its provision of that rich soil in which post-classical science could flourish and grow, it is hardly surprising that, in this imperfect world, it has detractors…

Allan Chapman, Slaying the Dragons: Destroying the Myths in the History of Science and Faith (Oxford, England: Lion Publishing, 2013), 18-23.

ISLAM’s “Golden Age” revisited

The Golden Age of Islam – A Second Look

…Victor Davis Hanson has taken down Obama’s version of the Golden age of Islam:

In his speech last week in Cairo, President Obama proclaimed he was a “student of history.” But despite Mr. Obama’s image as an Ivy League-educated intellectual, he lacks historical competency in both facts and interpretation. … Obama … claimed that “Islam . . . carried the light of learning through so many centuries, paving the way for Europe’s Renaissance and Enlightenment.” [In fact] medieval Islamic culture … had little to do with the European rediscovery of classical Greek and Latin values. Europeans, Chinese, and Hindus, not Muslims, invented most of the breakthroughs Obama credited to Islamic innovation. … Much of the Renaissance, in fact, was more predicated on the centuries-long flight of Greek-speaking Byzantine scholars from Constantinople to Western Europe to escape the aggression of Islamic Turks. Many romantic thinkers of the Enlightenment sought to extend freedom to oppressed subjects of Muslim fundamentalist rule in eastern and southern Europe.

Andrew Bostom has skewered the myth that Cordoba was a model of ecumenism:

Expanding upon Jane Gerber’s thesis about the “garish” myth of a “Golden Age,” the late Richard Fletcher (in his Moorish Spain) offered a fair assessment of interfaith relationships in Muslim Spain and his view of additional contemporary currents responsible for obfuscating that history:

The witness of those who lived through the horrors of the Berber conquest, of the Andalusian fitnah [ordeal] in the early eleventh century, of the Almoravid invasion — to mention only a few disruptive episodes — must give it [i.e.: the roseate view of Muslim Spain] the lie.

The simple and verifiable historical truth is that Moorish Spain was more often a land of turmoil than it was of tranquility. … Tolerance? Ask the Jews of Granada who were massacred in 1066, or the Christians who were deported by the Almoravids to Morocco in 1126 (like the Moriscos five centuries later). … In the second half of the twentieth century a new agent of obfuscation makes its appearance: the guilt of the liberal conscience, which sees the evils of colonialism — assumed rather than demonstrated — foreshadowed in the Christian conquest of al-Andalus and the persecution of the Moriscos (but not, oddly, in the Moorish conquest and colonization). Stir the mix well and issue it free to credulous academics and media persons throughout the Western world. Then pour it generously over the truth … in the cultural conditions that prevail in the West today, the past has to be marketed, and to be successfully marketed, it has to be attractively packaged. Medieval Spain in a state of nature lacks wide appeal. Self-indulgent fantasies of glamour … do wonders for sharpening its image. But Moorish Spain was not a tolerant and enlightened society even in its most cultivated epoch.

Serge Trifkovic also has a general take-down of the overblown account of the accomplishments and comity of the Islamic Golden Age in his FrontPage article, The Golden Age of Islam is a Myth.

And now we have Emmet Scott, in a soon to be released study, Mohammed & Charlemagne Revisited: An Introduction to the History of a Controversy, advancing the thesis that Rather than preserving the Classical heritage, the expanding Islamic empire destroyed it and brought about the Dark Ages.

Armed with new archaeological evidence, Scott makes the compelling case, originally put forward in 1920 by Henri Pirenne, a Belgian historian, that Classical civilization did not collapse after the fall of the Roman empire but was gradually attrited by the onslaught of Arab armies and raiders. The Islamic Golden Age came close to permanently destroying the classical humanistic culture of the West.

Hanson has pointed out the factual errors in Obama’s paean to Islam’s Golden Age. Andrew Bostom has skewered the myth that Cordoba was a model of ecumenism Trikovic has shown that the continuation of learning, science, technology of the “Golden age of Islam” prospered in spite of Islam and not because of Islam and now we have Emmet Scott skewering the myth that the Golden Age of Islam saved Classical humanistic Western culture. What is next? The glory of Sharia?

See also my past posts on the topic: