I updated this post with some more early church father “stuff.” Feel free to jump to the excerpt/graph and additional info. Jump to my other posts so far on the topic of Calvinism:

I updated this post with some more early church father “stuff.” Feel free to jump to the excerpt/graph and additional info. Jump to my other posts so far on the topic of Calvinism:

To go to all my posts on Calvinism and related issues, click the graphic to the right.

Enjoy the rest

Ken Wilson Rebuts James White

Description from the above video on SOTERIOLOGY 101’s YouTube:

Dr. Leighton Flowers welcomes back Dr. Ken Wilson to defend his Oxford Thesis from over 15 hours of mostly fallacious and unfounded attacks by Dr. James White of Alpha and Omega Ministries.

The Common Misconceptions in this Debate So Far:

- Wilson’s argument rests on Manicheanism and Augustinianism being the same worldview: This is untrue. It is not at all unreasonable to suggest that just one aspect of Manicheanism (i.e. its adherence to theistic determinism) might have influenced Augustine’s interpretation of the scripture.

- Wilson is saying Augustinianism is untrue because of its similarities with Manicheanism: This is inaccurate. It is possible for false worldviews to adhere to some aspects of truth, therefore proving that Calvinism has some link to Manicheanism doesn’t prove Calvinism is false. Wilson is saying Augustinianism is not rooted or founded in the early church writings therefore it most likely originated from other gnostic, neoplatonic and Manichean roots, which brings into question its validity as the correct interpretive grid.

- Wilson is arguing Augustinianism imports Manicheanism into Christianity because it uses similar words: This is also untrue. Just because Mani spoke of “the elect” and Calvinists also emphasize “the elect” does not mean they are necessarily linked, or even have the same definitions. Wilson is not attempting to argue that all aspects or jargon of the Manichean worldview are linked to the all aspects or jargon within the Calvinistic worldview. Wilson is only looking at the one common point of connection, namely deterministic philosophy, which was first introduced by Augustine, a former Manichean.

- James White’s criticism has accurately portrayed Wilson’s arguments and showed Wilson’s bias: This is demonstrably untrue as will be shown in this video and in many of the articles posted at www.soteriology101.com.

- If it can be proven that Wilson held to preconception of the ECFs and Augustine’s beliefs before doing his research, then his subsequent research is invalid: Again this is false. Even if it could be proven beyond all reasonable doubt that Wilson firmly believed the ECFs denied TULIP theology and that Augustine was the first to introduce it, this does not make his findings invalid. One would still need to demonstrate that Wilson’s bias lead to poor research.

Here are quotes from Reformed historians who validate the foundational claims of Wilson’s work:

Herman Bavinck:

- In the early church, at a time when it had to contend with pagan fatalism and gnostic naturalism, its representatives focused exclusively on the moral nature, freedom, and responsibility of humans and could not do justice, therefore, to the teaching of Scripture concerning the counsel of God. Though humans had been more or less corrupted by sin, they remained free and were able to accept the proffered grace of God. The church’s teaching did not include a doctrine of absolute predestination and irresistible grace.

Loraine Boettner:

- “It may occasion some surprise to discover that the doctrine of Predestination was not made a matter of special study until near the end of the fourth century….They of course taught that salvation was through Christ; yet they assumed that man had full power to accept or reject the gospel. Some of their writings contain passages in which the sovereignty of God is recognized; yet along side of those are others which teach the absolute freedom of the human will. Since they could not reconcile the two they would have denied the doctrine of Predestination… They taught a kind of synergism in which there was a co-operation between grace and free … this cardinal truth of Christianity was first clearly seen by Augustine…“

Robert Peterson and Michael Williams of Covenant Theological Seminary:

- “The Semi-Pelagians were convinced that Augustine’s monergistic emphasis upon salvation by grace alone represented a significant departure from the traditional teaching of the church. And a survey of the thought of the apostolic father’s shows that the argument is valid… In comparison to Augustine’s monergistic doctrine of grace, the teachings of the apostolic fathers tended toward a synergistic view of redemption” (36).

Louis Berkhof [in The History of Christian Doctrines]:

- “Their representations are naturally rather indefinite, imperfect, and incomplete, and sometimes even erroneous and self-contradictory. Says Kahnis: “It stands as an assured fact, a fact knowing no exceptions, and acknowledged by all well versed in the matter, that all of the pre-Augustinian Fathers taught that in the appropriation of salvation there is a co-working of freedom and grace.”

Berkhof goes on to admit that “they do not hold to an entire corruption of the human will, and consequently adhere to the synergistic theory of regeneration…” (130).

In other words, despite White’s assertions to the contrary, there were no “monergists” before Augustine.

An additional — fuller quote of Loraine Boettner from above:

- “It may occasion some surprise to discover that the doctrine of Predestination was not made a matter of special study until near the end of the fourth century. The earlier church fathers placed chief emphasis on good works such as faith, repentance, almsgiving, prayers, submission to baptism, etc., as the basis of salvation. They of course taught that salvation was through Christ; yet they assumed that man had full power to accept or reject the Gospel. Some of their writings contain passages in which the sovereignty of God is recognized; yet along side of those are others which teach the absolute freedom of the human will. Since they could not reconcile the two they would have denied the doctrine of Predestination and perhaps also that of God’s absolute Foreknowledge. They taught a kind of synergism in which there was a co-operation between grace and free will. It was hard for man to give up the idea that he could work out his own salvation. But at last, as a result of a long, slow process, he came to the great truth that salvation is a sovereign gift which has been bestowed irrespective of merit; that it was fixed in eternity; and that God is the author in all of its stages. This cardinal truth of Christianity was first clearly seen by Augustine, the great Spirit-filled theologian of the West. In his doctrines of sin and grace, he went far beyond the earlier theologians, taught an unconditional election of grace, and restricted the purposes of redemption to the definite circle of the elect.” — from Loraine Boettner’s “Calvinism in History”

Here is chapter two from Ken Wilson’s book, “The Foundation of Augustinian-Calvinism” (PDF as well)

Here is a good review of the book via the South African Theological Seminary.

See also my first post commenting on this issue.

Chapter 2

Early Christian Authors 95–400 CE

Early Christian authors unanimously taught relational divine eternal predetermination. God elected persons to salvation based upon foreknowledge of their faith (predestination). These Christians vigorously opposed the unilateral determinism of Stoic Providence, Gnosticism, and Manichaeism.[48] So early Christians taught predestination,[49] but refuted Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies (unilateral determinism). This unilateral determinism can be identified in ancient Iranian religion, then chronologically in the Qumranites, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and Manichaeism. “Christian” heretics such as Basilides who taught God unilaterally bestowed the gift of faith to only some persons (and withheld that salvific gift to others) were condemned. Of the eighty-four pre-Augustinian authors studied from 95–430 CE, over fifty addressed this topic. All of these early Christian authors championed traditional free choice and relational predestination against pagan and heretical Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies.[50]

This can only be understood and appreciated by reading comprehensively through the sizeable number of works by these authors. Some persons triumphantly cite ancient Christian authors claiming they believe Augustine’s deterministic interpretations of scripture, but without reading the entire context or without understanding the way in which words were being used.[51] I am not aware of any Patristics (early church fathers) scholar who would or could make a claim that even one Christian author prior to Augustine taught Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies (DUPIED, i.e., non-relational determinism unrelated to foreknowledge of human choices).

I. Apostolic Fathers and Apologists 95–180 CE

Most of these works do not directly address God’s sovereignty or free will.[52] The Epistle of Barnabas (100–120 CE) admits the corruption of human nature (Barn.16.7) but only physical death (not spiritual) results from Adam’s fall. Personal sins cause a wicked heart (Barn.12.5). Divine foreknowledge of human choices allowed the Jews to make choices and remain within God’s plan, resulting in their own self-determination (Barn.3.6). God’s justice is connected with human responsibility (Barn.5.4). Therefore, God’s foreknowledge of human choices should affect God’s actions regarding salvation.

In The Epistle of Diognetus (120–170 CE) God does not compel anyone. Instead, God foreknows choices by which he correspondingly chooses his responses to humans. Meecham writes of Diogn.10.1–11.8, “Free-will is implied in his capacity to become ‘a new man’ (ii,I), and in God’s attitude of appeal rather than compulsion (vii, 4).”[53] Aristides (ca.125–170 CE) taught newborns enter the world without sin or guilt: only personal sin incurs punishment.[54]

II. Justin Martyr and Tatian

The first author to write more specifically on divine sovereignty and human free will is Justin Martyr (ca.155 CE). Erwin Goodenough explained:

Justin everywhere is positive in his assertion that the results of the struggle are fairly to be imputed to the blame of each individual. The Stoic determinism he indignantly rejects. Unless man is himself responsible for his ethical conduct, the entire ethical scheme of the universe collapses, and with it the very existence of God himself.[55]

Commenting on Dial.140.4 and 141.2, Barnard concurred, saying God “foreknows everything—not because events are necessary, nor because he has decreed that men shall act as they do or be what they are; but foreseeing all events he ordains reward or punishment accordingly.”[56] After considering 1 Apol.28 and 43, Chadwick also agreed. “Justin’s insistence on freedom and responsibility as God’s gift to man and his criticism of Stoic fatalism and of all moral relativism are so frequently repeated that it is safe to assume that here he saw a distinctively Christian emphasis requiring special stress.”[57] Similarly, Barnard wrote: “Justin, in spite of his failure to grasp the corporate nature of sin, was no Pelagian blindly believing in man’s innate power to elevate himself. All was due, he says, to the Incarnation of the Son of God.”[58]

Tatian (ca.165) taught that free choice for good was available to every person. “Since all men have free will, all men therefore have the potential to turn to God to achieve salvation.”[59] This remains true even though Adam’s fall enslaved humans to sin (Or.11.2). The fall is reversed through a personal choice to receive God’s gift in Christ (Or.15.4). Free choice was the basis of God’s rewards and punishments for both angels and humans (Or.7.1–2).

II. Theophilus, Athenagoras, and Melito

Theophilus (ca.180), all creation sinned in Adam and received the punishment of physical decay, not eternal death or total inability (Autol.2.17). Theophilus’ insistence upon a free choice response to God (Autol.2.27) occurs following his longer discussion of the primeval state in the Garden and subsequent fall of Adam. Christianity’s gracious God provides even fallen Adam with opportunity for repentance and confession (Autol.2.26). Theophilus exhorts Christians to overcome sin through their residual free choice (Autol.1.2, 1.7).

Athenagoras (ca.170 CE) believed infants were innocent and therefore could not be judged and used them as a proof for a bodily resurrection prior to judgment (De resurr.14). For God’s punishment to be just, free choice stands paramount. Why?—because God created both angels and persons with free choice for the purpose of assuming responsibility for their own actions (De resurr.24.4–5)[60] Humans and angels can live virtuously or viciously: “This, says Athenagoras, is a matter of free choice, a free will given the creature by the creator.”[61] Without free choice, the punishment or rewarding of both humans and angels would be unjust.

In Peri Pascha 326–388, Melito (ca.175 CE) possibly surpassed any extant Christian author in an extended description depicting the devastation of Adam’s fall.[62] The scholar Lynn Cohick explained: “The homilist leaves no doubt in the reader’s mind that humans have degenerated from a pristine state in the garden of Eden, where they were morally innocent, to a level of complete and utter perversion.”[63] Despite this profound depravity, all persons remain capable of believing in Christ through their own God-given free choice. No special grace is needed. A cause and effect relationship exists between human free choice and God’s response (P.P.739–744). “There is no suggestion that sinfulness is itself communicated to Adam’s progeny as in later Augustinian teaching.”[64]

B. Christian Authors 180–250 CE

I. Irenaeus of Lyons

Irenaeus of Lyons (ca.185) wrote primarily against Gnostic deterministic salvation in his famous work Adversus Haereses. “One position fundamental to Irenaeus is that man should come to moral good by the action of his own moral will, and not spontaneously and by nature.”[65] Physical death for the human race from Adam’s sin was not so much a punishment as God’s gracious gift to prevent humans from living eternally in a perpetual state of struggling with sin (Adv. haer.3.35.2).

Irenaeus championed humanity’s free will for four reasons: (1) to refute Gnostic Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies, (2) because humanity’s persisting imago Dei (image of God within humans) demands a persisting free will, (3) scriptural commands demand free will for legitimacy, and (4) God’s justice becomes impugned without free will (genuine, not Stoic “non-free free will”). These were non-negotiable “apostolic doctrines.” Scholars Wingren and Donovan both identify Irenaeus’ conception of the imago Dei as freedom of choice itself. As Donovan relates: “This strong affirmation of human liberty is at the same time a clear rejection of the Gnostic notion of predetermined natures.”[66]

Andia clarified that God’s justice requires free choice since Irenaeus believed God’s providence created all persons equally.[67] In refuting Gnostic determinism (Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies), Irenaeus argues that God determines persons’ eternal destinies through foreknowledge of the free choices of persons (Adv. haer.2.29.1; 4.37.2–5; 4.29.1–2; 3.12.2,5,11; 3.32.1; 4.14, 4.34.1, 4.61.2). Irenaeus attacked both Stoicism and Gnostic heresies because DUPIED made salvation by faith superfluous, and made Christ’s incarnation unnecessary.[68] Irenaeus taught God’s predestination. This was based on God’s foreknowledge of human choices without God constraining the human will as in Gnostic determinism.[69]

Irenaeus denied that any event could ever occur outside of God’s sovereignty (Adv. haer.2.5.4), but simultaneously emphasized residual human free choice to receive God’s gift, which only then results in regeneration. “The essential principle in the concept of freedom appears first in Christ’s status as the sovereign Lord, because for Irenaeus man’s freedom is, strangely enough, a direct expression of God’s omnipotence, so direct in fact, that a diminution of man’s freedom automatically involves a corresponding diminution of God’s omnipotence.”[70] Although he exalted God’s sovereignty, it was not (erroneously) defined as God receiving everything he desires.[71] The scholar Denis Minns correctly states, “Irenaeus would insist as vigorously as Augustine that nothing could be achieved without grace. But he would have been appalled at the thought that God would offer grace to some and withhold it from others.”[72]

II. Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian

Clement of Alexandria (ca.190) strongly defends a residual human free choice after Adam (Strom.1.1; cf. 4.24, 5.14). Divine foreknowledge determines divine election (Strom.1.18; 6.14). Clement understood that God calls all (lläv1ωv iοίvuv àvOρdrnωv)—every human, not a few of every kind of human —whereas, “the called” are those who respond. He believed that if God exercised Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies (as the Marcionites and Gnostics believed), then he would not be the just and good Christian God but the heretical God of Marcion (Strom.5.1).

Clement refuted the followers of the Gnostic Marcion who believed initial faith was God’s gift. Why?—it robbed humans of free choice (Strom.2.3–4; cf. Strom.4.11, Quis dives Salvetur 10). Yet Clement does not believe free choice saves persons as a human work (cf. John 1:13). He teaches God must first draw and call every human to himself, since all have the greatest need for the power of divine grace (Strom.5.1). God does not initiate a mystical (i.e., Neoplatonic) inward draw to each of his elect. Instead, the Father previously revealed himself and drew every human through Old Testament scripture, but now reveals himself and draws all humanity equally to himself through Christ and the New Testament (cf. John 12:32; Strom.7.1–2).[73]

Tertullian (ca.205) wrote that despite a corrupted nature, humans possess a residual capacity to accept God’s gift based upon the good divine image (the “proper nature”) still resident within every human (De anima 22). Every person retains the capacity to believe. He refuted Gnosticism’s discriminatory deterministic salvation (Val.29). God remains sovereign while he permits good and evil, because he foreknows what will occur by human free choice (Cult. fem.2.10). Humans can and should respond to God by using their God-given innate imago Dei free choice. Therefore, Tertullian did not approve of an “innocent” infant being baptized before responding personally to God’s gift of grace through hearing and believing the gospel (De baptismo 18). He believed that children should await baptism until they are old enough to personally believe in Christ.

III. Origen of Alexandria

Origen (ca.185–254) advances scriptural arguments for free choice that fill the third book of De principiis (P. Arch.3.1.6). “This also is definite in the teaching of the Church, every rational soul is possessed of free-will and volition” that can choose the good (Princ., Pref.5). God does not coerce humans or directly influence individuals but instead only invites. Why?—because God desires willing lovers. Just as Paul asked Philemon to voluntarily (κατὰ Eκοuσιοv) act in goodness (Phlm. 1.14), so God desires uncoerced lovers (Hom. Jer.20.2). Origen explains how God hardens Pharaoh’s heart. God sends divine signs/events that Pharaoh rejects and hardens his own heart. God’s hardening is indirect. “Now these passages are sufficient of themselves to trouble the multitude, as if man were not possessed of free will, but as if it were God who saves and destroys whom he will” (Princ. 3.1.7). Origen distinguishes between God’s temporal blessings and eternal destinies in Romans 9–11, rejecting the Gnostic eternal salvation view from these chapters.

Initial faith is human faith, not a divine gift. “The apostles, once understanding that faith which is only human cannot be perfected unless that which comes from God should be added to it, they say to the Savior, ‘Increase our faith.'” (Com.Rom.4.5.3). God desires to give the inheritance of the promises not as something due from debt but through grace. Origen says that the inheritance from God is granted to those who believe, not as the debt of a wage but as a gift of [human] faith (Com.Rom.4.5.1).[74]

Election is based upon divine foreknowledge. “For the Creator makes vessels of honor and vessels of dishonor, not from the beginning according to His foreknowledge, since He does not pre-condemn or pre-justify according to it; but (He makes) those into vessels of honor who purged themselves, and those into vessels of dishonor who allowed themselves to remain unpurged” (P.Arch.3.1.21). Origen does not refute divine foreknowledge resulting in election but refutes the philosophical view of foreknowledge as necessarily causative, which Celsus taught:

Celsus imagines that an event, predicted through foreknowledge, comes to pass because it was predicted; but we do not grant this, maintaining that he who foretold it was not the cause of its happening, because he foretold it would happen; but the future event itself, which would have taken place though not predicted, afforded the occasion to him, who was endowed with foreknowledge, of foretelling its occurrence (C.Cels.2.20).

Origen explains the Christian interpretation of Rom 9:16.[75] The Gnostic and heretical deterministic interpretations render God’s words superfluous, and invalidate Paul’s chastisements and approbations to Christians. Nevertheless, the human desire/will is insufficient to accomplish salvation, so Christians must rely upon God’s grace (P. Arch.3.1.18). Origen does not minimize the innate human sin principle that incites persons to sin. Rather, he chastises immature Christians who blame their sins on the devil instead of their own passions (Princ.3.2.1–2; P. Arch.3.1.15).

IV. Cyprian and Novatian

Cyprian (d.254 CE) taught God stands sovereign (Treat.3.19; 5.56.8; 12.80). Yet, God rewards or punishes based upon his foreknowledge of human choices and responses (Treat.7.17, 19; Ep.59.2). Humans retain free choice despite Adam’s sin (Treat.7.17, 19).[76] “That the liberty of believing or of not believing is placed in freedom of choice” (Treat.12.52). Jesus utilized persuasion, not force (Treat.9.6). Obedience resulting in martyrdom should arise from free choice, not necessity (Treat. 7.18), especially since imitating Christ restores God’s likeness.

Novatian (ca.250 CE) teaches a personal responsibility for sin instead of guilt from Adam, because a person who is pre-determined due to (even fallen) nature cannot be held liable. Only a willful decision can incur guilt (De cib. Jud.3). Lactantius (ca.315 CE) taught Adam’s fall produced only physical death (not eternal death) through the loss of God’s perpetually gifted immortality (Inst.2.13), as Williams correctly identified.[77] Yet, mortality in a corrupted human body predisposed the human race to sin (Inst.6.13). God loves every person equally, offers immortality equally to each person, and every human is capable of responding to God’s offer—without divine intervention (Div.inst.5.15) “God, who is the guide of that way, denies immortality to no human being” but offers salvation equally to every person (Div.inst.6.3). Humanity must contend with its propensity to sin, but the corrupted nature provides no excuse since free choice persists (Inst.2.15; 4.24; 4.25; 5.1). He consistently teaches Christian free choice (Inst.5.10, 13, 14).

C. Christian Authors 250–400 CE

I. Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary (d.368 CE) referred to John 1:12–13 as God’s offer of salvation that is equally offered to everyone. “They who do receive Him by virtue of their faith advance to be sons of God, being born not of the embrace of the flesh nor of the conception of the blood nor of bodily desire, but of God […] the Divine gift is offered to all, it is no heredity inevitably imprinted but a prize awarded to willing choice” (Trin.1.10–11). Human nature has a propensity to evil (Trin.3.21; Hom. Psa.1.4) that is located in the physical body (Hom. Psa.1.13). Human free choice elicits the divine gift, yet the divine birth (through faith) belongs solely to God. A human ‘will’ cannot create the birth (Trin.12.56) yet that birth occurs through human faith.

II. The Cappadocians

Gregory of Nazianzus (ca.329–389 CE) writes frequently of the “fall of sin” from Adam (Or.1; 33.9; 40.7), including the evil consequence of that original sin (Or.45.12). “We were detained in bondage by the Evil One, sold under sin, and receiving pleasure in exchange for wickedness” (Or.45.22). Salvation (not faith) is God’s gift. “We call it the Gift, because it is given to us in return for nothing on our part” (Or.40.4). “This, indeed, was the will of Supreme Goodness, to make the good even our own, not only because it was sown in our nature, but because cultivated by our own choice, and by the motions of our free will to act in either direction.” (Or.2.17). “Our soul is self-determining and independent, choosing as it will with sovereignty over itself that which is pleasing to it” (Ref.Conf. Eun.139). Children are born blameless (Ep.206). God is sovereign, and Christ died for all humankind, including the ‘non-elect.’ (Or.45.26; cf. Or.38.14). Nevertheless, in matters of personal salvation, God limits himself, allowing humans free choice (Or.32.25, 45.8).

Basil of Caesarea (ca.330–379 CE) believed humans do not inherit sin or evil, but choose to sin resulting in death. We control our own actions, proved by God’s payment and punishment (Hom. Hex.2.4). He promotes God’s sovereignty over human temporal (not eternal) destinies, including our time of death by “God who ordains our lots” (Ep.269) yet he refutes micromanaging Stoic Providence (Ep.151). God empowers human faith for great works because mere human effort cannot accomplish divine good (Ep.260.9). Basil allowed no place for either Chaldean astrological fatalism (Hom. Hex.6.5; Ep.236), or Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies. Righteous judgment resulting in reward and punishment demands Christian traditional free choice. In contrast, any concept of inevitable evil in humans necessarily destroys Christian hope (Hom. Hex.6.7) because all humans have an innate natural reason with the ability to do good and avoid evil (Hom. Hex.8.5; cf. Ep.260.7). Basil refuted a dozen heresies, but reserved his strongest denunciation for the one teaching determinism—”the detestable Manichaean heresy” (Hom. Hex.2.4).

Gregory of Nyssa (ca.335–395 CE) pervasively teaches a post-Adamic congenital weakness, inclined to evil and in slavery to sin but without guilt (C. Eun.1.1; 3.2–3; 3.8; De opificio hom.193; Cat. mag.6, 35; Ep.18; Ref. conf. Eun.; Dial. anim. et res., etc.). Each person’s alienation from God occurs through personal sin and vice, not Adam’s sin (C. Eun.3.10). Despite an inherited tendency to evil, the divine image within humans retains goodness, just as Tertullian and others had taught (Opif. hom.164; cf. Ep.3.17).[78] Humanity’s ruin and inability to achieve eternal life by self-effort demanded God initiate the rescue through Christ (Ref. conf. Eun.418–20). But Gregory refutes the idea of a human nature so corrupted that it would render an individual incapable of a genuine choice to receive God’s readily available gift of grace offered to everyone equally.

By appealing to the justice of God’s recompenses, Gregory refutes those [e.g., Manichaeans] who believe humans are born sinful and thus culpable (De anim.120). The choice for salvation belongs to humans, apart from God’s manipulation, coercion, or unilateral intervention (C. Eun.3.1.116–18; cf. Adv. Mac. spir. sancto 105–6; De virginitate 12.2–3). Gregory upholds Christian [not Stoic] divine sovereignty (Ref. conf. Eun. 169; cf. 126–27; Opif. hom.185).

III. Methodius, Theodore, and Ambrose

Methodius (d.312 CE) believed all humans retain genuine free will even after Adam’s fall since Christian free choice was necessary for God to be just in rewarding the good and punishing the wicked (Symp.8.16; P G 18:168d). He championed traditional Christian free choice in a major work against Gnostic determinism (Peri tou autexousiou, 73–77).[79] Cyril of Jerusalem (ca.348–386 CE) taught humans enter this world sinless (Cat.4.19) and God’s foreknowledge of human responses determines the divine choosing of them for service (Cat.1.3).

Theodore of Mopsuestia (ca.350–428 CE) defended traditional original sin against Manichaean damnable inherited guilt (Adv. def. orig. pecc.), so that, “Man’s freedom takes the first step, which is afterwards made effective by God … [with] the will of each man as being absolutely free and unbiased and able to choose either good or evil.”[80] Humans retain the ability to choose good and evil (Comm. Ioh.5.19).

Ambrose of Milan (d.397 CE) baptized Augustine in Milan on Easter in 387 CE. He taught traditional (not Augustinian) original sin (De fide 5.5, 8, 60; Exc. Satyri 2.6; cf. 1.4). Ambrose believed slavery to sin [the sin propensity] was inherited, but this was not literal sin that produced personal culpability and damnation (De Abrah.2.79). The scholar Paul Blowers noted, “Ambrosiaster (Rom.5:12ff) and Ambrose (Enar.in Ps.38.29) … both authors concluded that individuals were ultimately accountable only for their own sins.”[81]

Ambrose emphasized God predestined individuals based upon his foreknowledge of the future, concerning which God was omniscient (Ep.57; De fide 2.11, 97). God compels no one, but patiently waits for a human response in order that He may provide grace, preferring pity over punishment (Paen.1.5). He insisted upon residual free choice and views an increase in a person’s faith (not initial faith) as a divine gift given in response to faithfulness. (Paen.1.48; Ep.41.6).

D. Conclusion

Not even one early church father writing from 95–430 CE—despite abundant acknowledgement of inherited human depravity—considered Adam’s fall to have erased human free choice to independently respond to God’s gracious invitation.[82] God did not give initial faith as a gift. Humans could do nothing to save themselves—only God’s grace could save. Total inability to do God’s good works without God’s grace did not mean inability to believe in Christ and prepare for baptism. No Christian author embraced deterministic Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies (DUPIED): all who considered it rejected DUPIED as an erroneous pagan Stoic or Neoplatonic philosophy, or a Gnostic or Manichaean heresy, unbefitting Christianity’s gracious relational God. God’s gift was salvation by divine grace through human faith (cf. Eph. 2:8), not a unilateral initial faith gift, as the Gnostics and Manichaean heretics were claiming. Early Christian literature could be distinguished from Gnostic and Manichaean literature by this essential element.

In a seemingly rare theological unanimity over hundreds of years and throughout the entire Mediterranean world, a Christian regula fidei (rule of faith) of free choice (advocated by Origen as the rule of faith) combated the Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Individuals’ Eternal Destinies espoused in Stoicism’s “non-free free will” and Gnosticism’s divine gift of infused initial faith into a “dead will.” The loving Christian God allowed humans to exercise their God-given free will.

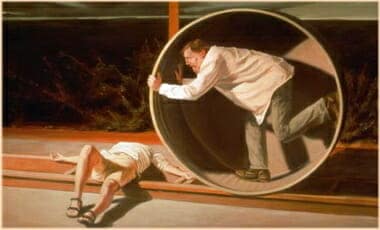

Graph

Click To Enlarge

Footnotes

Abbreviations from Ken Wilsons Augustine Book (PDF)

[48] Sarah Stroumsa and Guy. G. Stroumsa, “Anti-Manichaean Polemics in Late Antiquity and under Early Islam,” HTR 81 (1988): 48.

[49] Wallace wrongly claims, “In spite of the numerous New Testament references to predestination, patristic writers, especially the Greek fathers, tended to ignore the theme before Augustine of Hippo. This was probably partly the result of the early church’s struggle with the fatalistic determinism of the Gnostics”; Dewey Wallace, Jr. “Free Will and Predestination: An Overview,” in Lindsay Jones, ed. The Encyclopedia of Religion. 2nd edn., vol.5. (Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 3203. He obviously had not read Irenaeus and other early authors. For a cogent refutation of this absurd claim, see in the same volume C.T. McIntire (2005), “Free Will and Predestination: Christian Concepts,” vol.5, 3207.

[50] Wilson, Augustine’s Conversion, Appendix III, 307–309.

[51] Wilson, Augustine’s Conversion, 41–94, and see other comments in the work revealing how this occurs.

[52] For The Shepherd of Hermas and other works not covered here see Wilson, Augustine’s Conversion, 41–50.

[53] Henry Meecham, The Epistle to Diognetus: The Greek Text (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1949), 29–30.

[54] Harold Forshey, “The doctrine of the fall and original sin in the second century,” Restoration Quarterly 3 (1959): 1122, “But in this instance the doctrinal presupposition shows through clearly—a child comes into the world with a tabula rasa.“

[55] Erwin Goodenough, The Theology of Justin Martyr (Jena: Verlag Frommannsche Buchhandlung, 1923), 219.

[56] Leslie Barnard, Justin Martyr: His Life and Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 78.

[57] Henry Chadwick, “Justin Martyr’s Defence of Christianity,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 47.2 (1965): 284; cf., 291–292.

[58] Barnard (1967), 156.

[59] Emily Hunt, Christianity in the Second Century: The Case of Tatian (New York, NY: Routledge, 2003), 49.

[60] Bernard Pouderon, Athénagore d’Athênes, philosophie chrétien (Paris: Beauchesne, 1989), 177– 178. Pouderon highlighted this requisite for God’s law and justice: “La liberté humaine se tire de la notion de responsabilité: ‘L’homme est responsable (lllóöικοc) en tant qu’ensemble, de toutes ses actions’ (D.R.XVIII, 4).” “Human freedom results from the concept of responsibility: ‘Man is generally responsible (lllóöικοc) for all his actions.'” (my translation)

[61] David Rankin, Athenagoras: Philosopher and Theologian. Surrey: Ashgate, 2009), 180.

[62] Stuart Hall, Melito of Sardis: On Pascha and Fragments in Henry Chadwick, ed. Oxford Early Christian Texts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), xvi, where The Petition To Antonius “is now universally regarded as inauthentic.”

[63] Lynn Cohick, The Peri Pascha Attributed to Melito of Sardis: Setting, Purpose, and Sources (Providence, RI: Brown Judaic Studies, 2000), 115.

[64] Hall (1978), xlii.

[65] John Lawson, The Biblical Theology of Saint Irenaeus (London: The Epworth Press, 1948), 203.

[66] Gustaf Wingren, Man and the Incarnation, trans. by Ross Mackenzie (Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1947; repr., London: Oliver and Boyd, 1959), 36; Mary Ann Donovan, “Alive to the Glory of God: A Key Insight in St. Irenaeus,” TS 49 (1988): 291 citing Adv. haer.4.37.

[67] Ysabel de Andia, Homo vivens: incorruptibilité et divinisation de l’homme selon Irénée de Lyons (Paris: Études Augustiniennes, 1986), 131.

[68] E.P. Meijering, “Irenaeus’ relation to philosophy in the light of his concept of free will,” in E.P. Meijering, ed. God Being History: Studies in Patristic Philosophy (Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing, 1975), 23.

[69] James Beaven, An Account of the Life and Times of S. Irenaeus (London: Gilbert and Rivington, 1841), 165–166; F. Montgomery Hitchcock, Irenaeus of Lugdunum: A Study of His Teaching (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1914), 260; Wingren (1947; repr., 1959), 35–36.

[70] Wingren (1947; repr., 1959), 35–36.

[71] Explained later when discussing Augustine’s later specific sovereignty view.

[72] Denis Minns, Irenaeus (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1994), 136.

[73] Modern commentaries on this gospel rarely connect God’s drawing as being through scripture and Christ (John 6:44–45; 5.38–47; 8.19, 31, 47; 12.32). Cf. 1 Pet. 2.2.

[74] This serves as an excellent example of a passage removed from its context by which some persons erroneously attempt to prove an early church father taught faith was God’s gift.

[75] Rom. 9:16, “So it depends not upon man’s will or exertion, but upon God’s mercy.”

[76] For a refutation of Cyprian as teaching Augustine’s inherited guilt unto damnation see Wilson, Augustine’s Conversion, 77–82.

[77] Norman Williams, The Ideas of the Fall and Original Sin from the Bampton Lectures, Oxford University, 1924 (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1927), 297.

[78] C. Eunomium 24 (on the soul’s ability to see Christ) is probably post-baptismal.

[79] Patrologia orientalis 22:797–801. Cf. Roberta Franchi, Metodio di Olimpo: Il libero arbitrio (Milano: Paoline, 2015).

[80] Henry Wace, A Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects and Heresies (London: Murray, 1911), “Theodore, III.B.f.” This suggests Macarius was incorrect when he assumed that this work by Theodore was anti-Augustinian. It is defending traditional freedom of choice versus eternal damnation by inherited sin from being born physically, a Manichaean doctrine. The quotation is from Reginald Moxon, The Doctrine of Sin (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1922), 40.

[81] Paul Blowers, “Original Sin,” in Everett Ferguson, ed. Encyclopedia of Early Christianity. 2nd edn. (New York, NY: Routledge, 1999), 839–840.

In discussion with a friend who seemed like he did not watch the below video, I noted:

Calvinistic historian, Loraine Boettner, concedes that the concept of individual effectual election to salvation “was first clearly seen by Augustine” in the fifth century. John Calvin admits that his theology was first clearly seen in Augustine. Many reformers stood against many of these ideas… the scholar/Greek reader of the bunch, Phillipe Melanchthon, as well. Others were killed, like my homeboy Hubmaier.

We know currently – not standing in heaven after we pass, by Scripture – that God has allowed His prevenient grace to work thru Scripture [sharper than any two-edged sword] to change minds.

For the word of God is living and effective and sharper than any double-edged sword, penetrating as far as the separation of soul and spirit, joints and marrow. It is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart.

In the 5-point system God chooses wholly who believes and who does not. In other words, I do not believe God chose before creation who would be saved and who would not. It would be like the evil guy in the Incredibles – Omnidroid – who made the evil robots to destroy them in order to look like the good guy. When people realize the 5-points do this to the God of the Bible [Augustinianism], they understand how shallow the God of those points are.

Dr. Leighton Flowers, Director of Evangelism and Apologetics for Texas Baptists, gives a history lesson on the soteriological influence of Augustine and the Reformers in contrast to the Earlier church leaders and apologists. For more on Dr Ken Wilson’s work: Did the Early Church Fathers teach “Calvinism?”

There has been an attempt to respond to this, however, as you will see some misquoting is going on

Dr. Leighton Flowers, Director of Evangelism and Apologetics for Texas Baptists, is joined by Dr. Ken Wilson to discuss the history of Determinism in the church.

Dr. Leighton Flowers, Director of Evangelism and Apologetics for Texas Baptists, answers a listener submitted question about whether Calvinism is a form of Gnosticism.

UPDATED:

David L. Allen & Steve W. Lemke (gen editors), Calvinism: A Biblical and Theological Critique (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2022), 220-221, 225-226. From Kenneth Wilson’s chapter titled, “Calvinism is Augustinianism.”

- Acronym below you need to know, DUPED: Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Eternal Destinies (unconditional election)

Gnostics and Manichaeans Abused Christian

Scriptures to Prove Determinism

Gnostics and Manichaeans usurped Christian Scriptures to argue for their deterministic theologies. They were able to interpret certain passages through their own deterministic lenses and discover their own doctrines (eisegesis). Irenaeus (ca. AD 180) warned Christians about these heretical misuses of Scripture by Gnostics in his major book Against All Heresies.

Gnostics/Manichaeans had cited Rom 9:18–31 to prove DUPED (Divine Unilateral Predetermination of Eternal Destinies | unconditional election) with humans having no choice (Augustine, De Genesi ad litteram, 11.10–12 and Origen, Peri Archon, 3.1.21). Gnostics taught that divine foreknowledge proved pagan absolute determinism (Origen, Contra Celsum, 2.20; Philocalia, 23.7). They used Phil 2:13 to teach God gifted the “good will” only to the unilaterally chosen elect, resulting in salvation (Peri Archon, 3.1.20). The Valentinian Gnostics taught divine determinism without human free choice by using Romans 11 in a Stoic interpretation of sovereignty (Clement, Excerpta ex Theodoto, 56.3–27).[20]

The Manichaeans appealed to John 6:44–45 and 14:6. “No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him” (6:44) proved DUPED devoid of human choice/will (Contra litteras Petiliani, 2.185–186; Contra Fortunatum Manichaeum, 3; Ibid., 16–22). Manichaeans used Psalm 51:5 to prove all humans were damned at birth due to Adam’s sin (that Augustine refuted in Contra litteras Petiliani, 2.232). The 1 John 2:2 text had been used to argue Christ died only for the elect (Origen, Commentarii in evangelium Iohannis, 6.59; Commentarii Romanos, 3.8.13). Fortunatus the Manichaean cited Eph 2:3, 8–10 to support meticulous providence. Since spiritually dead persons cannot respond positively, God must unilaterally choose only the elect in rigid determinism by infusing faith (Contra Fortunatum Manichaeum, 14–21). Augustine, however, following the lead of all prior Christian authors, refuted the fatalistic determinism of Fortunatus and these Manichaean abuses of Scripture for twenty-five years. But, as we will now discover, he later reverted to his prior Manichaean deterministic interpretations [his later 18 years].

[….]

Thus, Augustine abandoned the unanimous consensus of the earlier Christian view and reverted to his Gnostic-Manichaean deterministic interpretations of Christian Scripture in AD 412. This can be best visualized by examining the following chart that compares the different interpretations of key Scripture passages by early Christians, Gnostic-Manichaeans, and Augustinian-Calvinists.

Gnostics and Manichaeans had used these same Christian Scriptures (listed above) for centuries to promote their unilateral determinism. Before Augustine, orthodox Christians had refuted heretical Gnostic and Manichaean DUPED and “interpreted proorizō [election] as depending upon proginoskō (foreknow)—those whom God foreknew would believe he decided upon beforehand to save. Their chief concern was to combat the concept of fatalism and affirm that humans are free to do what is righteous.”31

Augustine’s move toward DUPED was recognized by his peers, so he was accused of reverting to his prior Manichaean theology.32 But as a splendid rhetorician, Augustine defended himself brilliantly by creating a subtle distinction. He modified Gnostic/Manichaean “created human corrupt nature” (producing damnation) into a Christianized “fallen human corrupt nature” in Adam with inherited guilt (producing damnation; Nupt. et conc.2.16). Augustine’s novel nuanced “fallen” nature borrowed a key Gnostic/Manichaean and Neoplatonic doctrine: humans have total inability to respond to God until divinely awakened from spiritual death.

Furthermore, to avoid violating centuries of unanimous Christian teaching, Augustine had to redefine the Christian meaning of free will. He concluded God must micromanage and manipulate the circumstances that guarantee a person would “freely” respond to the invitation of God’s calling to eternal life.33 This should be compared to placing a mouse in a maze, then opening and closing doors so the mouse could “freely” reach the cheese. (In Christian theology that emphasized free will, all doors remained open for the maze traveler to choose his or her own path.) Augustine’s redefined free will was Stoic “non-free free will.” A millennium later, Calvinists would label this divine manipulation of the human free will by the term irresistible grace (God forcing a person to “love” him).

FOOTNOTES

[20] Jeffrey Bingham, “Irenaeus Reads Romans 8: Resurrection and Renovation,” in Early Patristic Readings of Romans, Romans Through History and Culture Series, ed. Kathy L. Gaca and L. L. Welborn (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 114–32.

[….]

[31] Carl Thomas McIntire, “Free Will and Predestination: Christian Concepts,” in The Encyclopedia of Religion, 15 vols., ed. Lindsay Jones, 2nd ed. (Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 5:3206–9.

[32] C. Jul. imp.1.52. His ordination as a bishop was blocked and almost prevented due to his prior Manichaeism. See Jason D. BeDuhn, “Augustine Accused: Megalius, Manichaeism, and the Inception of the Confessions,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 17, no. 1 (2009): 85–124; and Henry Chadwick, “Self-Justification in Augustine’s Confessions,” English Historical Review 178 (2003): 1168. As in the chart above, see Augustine’s Manichaean interpretations of Romans 9–11 (Pecc. merit.29–31, Spir. et litt.50, 60, 66; Nupt.2.31–32, C. du ep. Pelag.2.15, Enchir.98, C. Jul. 3.37,4.15, Corrept. 28); Eph 2:8–10 (Spir. et litt.56, C. du ep. Pelag., Enchir.31, Praed.12); John 14:6 and 6:44, 65 (C. du ep. Pelag.1.7, Grat.3–4,10); and Phil 2:13 (Spir. et litt.42, Grat. Chr.1.6, C. Jul.3.37, 4.15, Grat.32, 38).

[33] Patout Burns, “From Persuasion to Predestination: Augustine on Freedom in Rational Creatures,” in In Dominico Eloquio—In Lordly Eloquence: Essays on Patristic Exegesis in Honour of Robert Louis Wilken, ed. Paul M. Blowers, Angela R. Christman, David G. Hunter, and Robin D. Young (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 307.