Why This Post? I was attending a church recently after leaving a church my family and I attended for 10-years. At this new church I was vetting, I really enjoyed the people, the teaching, and the like — and was settling in a bit. They offered good solid food. But in conversation with an elder/assistant pastor about his schooling at Biola’s graduate school, a couple “red-flags” went up for me. This elder/assistant pastor stopped me when I mentioned Thomas Merton’s name during our discussion of my reasons for leaving my previous church. He mentioned he could not see anything wrong with Merton, and was even reading a book assigned to him in his graduate class at a Christian university. He offered to loan it to me, I politely opted to buy my own for inclusion in my library. This is the review of the book and the reason I left THAT church… for leadership to read through this book and not see a conflict with the Christian worldview means they do not understand the Christian worldview well. Well enough to Shepard that is.

- UPDATED. While I am certain that my church of 10-years is still a place where I would not recommend people go… I would not hold that same reservation for this church, which is why I have removed it’s name and link from this post. I trust the people who are on staff there. The teaching is sound. PLUS, it was very close to the time I had deep doctrinal concerns with my long-time church and was searching for a home church, so I was not going to stay and “battle it out” at that time. Later, the person with these views mentioned below was let go.

(Originally posted at RPT at Blogspot 3-18-2010.) As I have studied this subject and getting into some of the characters involved — many Catholic — I have thought to myself, is this reaching out in contemplative prayer a form of works? Does it make man the prime mover towards God as all too often many of the rituals in works oriented beliefs do. As I read along with Thomas Merton and other contemplatives, this thought became solidified for me. These Catholic monks and persons who separated themselves from society created many ritualistic works to commune with God (breath prayer, contemplative prayer, lectio divina, silence [which differs from physical solitude], palms up palms down, whatever).

Instead of going the way of Reformation using the Bible as their guide, studying the many Protestant Reformers and changing Catholic doctrine, praxology, and the like; thus, allowing God through Christ to fulfill in them the finished work that they try to achieve daily. Instead, they choose a pagan form of “freedom.” This freedom is called “darkness” by Merton (Chapter 5 in Merton’s Contemplative Prayer).

David Cloud, whom I find a bit legalistic, nevertheless shines through on this particular topic by documenting various works found in Catholicism. Lets just focus on one of them, the Mass:[1]

What could be more mystical than touching God with your hands and taking Him into your very being by eating him in the form of a wafer? In the Mass the strangely-clothed, mysterious priest (ordained after the order of Melchisedec) pronounces words that mystically turn a wafer of unleavened bread into the very body of Jesus. The consecrated wafer, called a host (meaning victim) is eaten by the people.

The sacrifice of Christ and the sacrifice of the Eucharist are one single sacrifice … ‘In this divine sacrifice which is celebrated in the Mass, the same Christ who offered himself once in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross is contained and offered in an unbloody manner (New Catholic Catechism, 1367) “In the liturgy of the Mass we express our faith in the real presence of Christ under the species of bread and wine by, among other ways, genuflecting or bowing deeply as a sign of adoration of the Lord…. reserving the consecrated hosts with the utmost care, exposing them to the solemn veneration of the faithful, and carrying them in procession” (New Catholic Catechism, 1378).

On some occasions one larger host is placed in a gaudy metal holder called a monstrance to be worshipped (“adored”) as God. This is called Eucharistic adoration.Eventually the host is placed in its own little tabernacle as the focus of worship between Masses. A lamp or a candle is lit to signify the fact that the consecrated host is present.This highly mystical ritual is multisensory, involving touch (dipping the finger into holy water and touching the wafer), sight (the splendor of the church, the priestly garments, the instruments of the Mass), smell (incense), hearing (reading, chanting, bells), and taste (eating the wafer).

The Mass is even said to bring the participant into “divine union” like other forms of contemplative mysticism (Thomas a Kempis, The Imitation of Christ, book IV, chap. 15, 4, p. 210).

The Second Vatican Council reaffirmed the centrality of the Mass in Catholic life:

“The celebration of the Mass … is the centre of the whole Christian life for the universal Church, the local Church and for each and every one of the faithful. For therein is the culminating action whereby God sanctifies the world in Christ and men worship the Father as they adore him through Christ the Son of God” (Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents, edited by Austin Flannery, 1975, “The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, General Instruction on the Roman Missal,” chap. 1, 1, p. 159).

The Catholic Mass is not a mere remembrance of Christ’s death; it is a re-sacrifice of Christ, and the consecrated host IS Christ. Consider statements from the authoritative Council of Trent, Second Vatican Council, and the New Catholic Catechism.”There is, therefore, no room for doubt that all the faithful of Christ may, in accordance with a custom always received in the Catholic Church, give to this most holy sacrament in veneration the worship of latria, which is due to the true God” (The Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent, translated by H. J. Schroeder, chap. v, “The Worship and Veneration to be Shown to This Most Holy Sacrament,” p. 76).”The victim is one and the same: the same now offers through the ministry of priests, who then offered himself on the cross; only the manner of offering is different. And since in this divine sacrifice which is celebrated in the Mass, the same Christ who offered himself once in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross is contained and offered in an unbloody manner… this sacrifice is truly propitiatory” (Council of Trent, Doctrina de ss. Missae sacrificio, c. 2, quoted in Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1367).

[….]

Before David Cloud ends the section on the Mass and jumps into his section on Labryinths, he finishes off his thinking with another example:

In the 1990s I visited a cloistered nunnery in Quebec. A pastor friend took me with him when he visited his aunt who had lived there for many decades. He and his wife wanted to show the nun their new baby. She wasn’t allowed to come out into the meeting room to see us; she had to stay behind a metal grill and talk to us from there. The nuns pray in shifts before the consecrated host in the chapel. That is their Jesus and the object of their prayers. At the entrance of the chapel there was a sign that said, “YOU ARE ENTERING TO ADORE THE JESUS-HOST.” Nuns were sitting in the chapel facing the host and praying their rosaries and saying their prayers to Mary and their “Our Fathers” and other repetitious mantras, vainly and sadly whiling away their lives in ascetic apostasy.

These work based religions can be dangerous for the soul; these practices of prayer as Thomas Merton lays out can be equally dangerous.

An example of this type of meditative practices leading to demonic presences masquerading as spirit guides can be found in Johanna Michaelsen’s book, The Beautiful Side of Evil. Johanna got involved in meditation and New Age/Eastern teachings and soon was being guided by multiple spirit guides, one of them being Jesus.[2] Who wouldn’t want to be lead by Jesus personally? Truly there is a way that seems right to a man but ultimately leads to deaths door (Proverbs 14:12).

How does Johanna’s experience connect in any way to Merton? If this technique were really a form a meditation influenced by Eastern practices leading to altered states of consciousness, you would expect some sort of warning about it if trying to Christianize it. Bingo.

Serious mistakes can be made…. when a person thinks he has attained to a certain facility in contemplation, he may find himself getting all kinds of strange ideas and he may, what is more, cling to them with a fierce dedication, convinced that they are supernatural graces and signs of God’s blessing upon his efforts when, in fact, they simply show that he has gone off the right track and is perhaps in rather serious danger…. Hence the traditional importance, in monastic life, of the “spiritual father,” who may be the abbot or another experienced monk capable of guiding the beginner in the ways of prayer, and of immediately detecting any sign of misguided zeal and wrong-headed effort. Such a one should be listened to and obeyed, especially when he cautions against the use of certain methods and practices, which he sees to be out of place and harmful in a particular case, or when he declines to accept certain “experiences” as evidence of progress.[3]

The above quote/book by Thomas Merton has the introduction written by Thich Nhat Hanh, who is a Zen Buddhist Monk. Mentioned quite a few times as well is Abbe J. Monchanin (Swami Parama Arubi Ananda), who founded a “Christian” Ashram. Which brings me to the reason for this post. A pastor asked me to read Esther de Waal’s book, A Seven Day Journey with Thomas Merton.

The above quote/book by Thomas Merton has the introduction written by Thich Nhat Hanh, who is a Zen Buddhist Monk. Mentioned quite a few times as well is Abbe J. Monchanin (Swami Parama Arubi Ananda), who founded a “Christian” Ashram. Which brings me to the reason for this post. A pastor asked me to read Esther de Waal’s book, A Seven Day Journey with Thomas Merton.

This pastor recommended the book as a healthier presentation of Merton than my previously posted biographical insights via RPT (see: Part I, Part II, Part III). I was happy to hear of a book that may correct some of my faulty thinking on the matter. I was open to view a book that would allay some of my fears, dare I say paranoia, that Eastern meditative practices had so infected the Evangelical denominations through this monk by combining panantheism with Christianity.

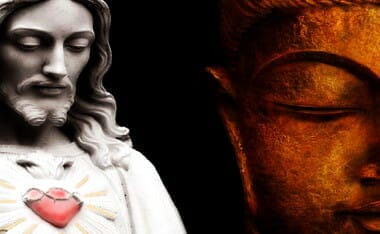

… What Buddhists like [Thich Nhat] Hanh do not understand is if the Buddhist interpretation of Jesus is correct then there is no Christian Gospel. If they are wrong and Jesus is who Christians believe Him to be then Buddhism cannot lead anyone to Enlightenment. These religions cannot be married together. Although they have some similar concepts in terms of love and peace, the roots of each religion go deeper than these concepts.

In Christianity Jesus is much more than a teacher – He is God. If Hanh is right in saying that Jesus and the Buddha are conceptual brothers then Christianity losses its root and will be forced to wither away. Conversely, if when Jesus said in John 14:6 “No one comes to the Father except through Me,” He excludes any other path to truth, then the Buddha is leading his disciples down a path of fruitless effort….

As I read along, alI was fine until page 14, where there started to be talk of “silence.” Silence, as Merton teaches, is not merely seclusion, but an emptying of the mind. The book often mentioned by these contemplatives, The Cloud of Unknowing, talks at length about this emptying – it’s called: this darkness, this nothingness, this nowhere, the blind experience of contemplative love. David Cloud documents some quotes from this book the Desert Fathers were very enthralled by. (I wish to quickly make the point that about the time these “Desert Fathers” were writing in the area of Egypt they resided, so too were the Gnostics [same area as well] writing their poison that still lives-on today in the Word Faith movement, in the Emergent movement, and various cults and the occult, Freemasonry as an example):[4]

“Do all in your power to forget everything else, keeping your thoughts and desires free from involvement with any of God’s creatures or their affairs whether in general or in particular … pay no attention to them” (The Cloud of Unknowing, edited by William Johnston, Image Books, 1973, chapter 3, p. 48).

“Thought cannot comprehend God. And so, I prefer to abandon all I can know, choosing rather to love him whom I cannot know. … By love he may be touched and embraced, never by thought. … in the real contemplative work you must set all this aside and cover it over with a cloud of forgetting” (chapter 6, pp. 54, 55).”…

dismiss every clever or subtle thought no matter how holy or valuable. Cover it over with a thick cloud of forgetting because in this life only love can touch God as he is in himself, never knowledge” (chapter 8, pp. 59, 60).”

So then, you must reject all clear conceptualizations whenever they arise, as they inevitably will, during the blind work of contemplative love. … Therefore, firmly reject all clear ideas, however pious or delightful” (chapter 9, p. 60).

The Book of Privy Counseling, written by the author of The Cloud of Unknowing, says:

“reject all thoughts, be they good or be they evil” (The Cloud of Unknowing and The Book of Privy Counseling, edited by William Johnston, Image Books, 1973, chapter 1, p. 149).

A mantra is the key to entering the non-thinking mode. The practitioner is taught to choose “a sacred word” such as love or God and repeat it until the mind is emptied and carried away into a non-thinking communion with God at the center of one’s being.

“… the little word is used in order to sweep all images and thoughts from the mind, leaving it free to love with the blind stirring that stretches out toward God” (William Johnston, The Cloud of Unknowing, introduction, p. 10).

The practitioner is taught that he must not think on the meaning of the word.

“… choose a short word … a one-syllable word such as ‘God’ or `love’ is best. … Then fix it in your mind so that it will be your defense in conflict and in peace. Use it to beat upon the cloud of darkness above you and to subdue all distractions, consigning them to the cloud of forgetting beneath you. … If your mind begins to intellectualize over the meaning and connotations of this little word, remind yourself that its value lies in its simplicity. Do this and I assure you these thoughts will vanish” (The Cloud of Unknowing, chapter 7, p. 56).

“… focus your attention on a simple word such as sin or God … and without the intervention of analytical thought allow yourself to experience directly the reality it signifies. Do not use clever logic to examine or explain this word to yourself nor allow yourself to ponder its ramifications …I do not believe reasoning ever helps in the contemplative work. This is why I advise you to leave these words whole, like a lump, as it were” (The Cloud of Unknowing, chapter 36, p. 94).

The attempt to achieve a mindless mystical condition through a mantra can produce a hypnotic state and open one to demonic activity. Even if you don’t consciously try to lose the meaning of the word, it quickly becomes lost to the mind. Ray Yungen, who has done extensive and excellent research into the New Age, explains:

“When a word or phrase is repeated over and over, after just a few repetitions, those words lose their meaning and become just sounds. … After three or four times, the word can begin to lose its meaning, and if this repeating of words were continued, normal thought processes could be blocked, making it possible to enter an altered state of consciousness because of the hypnotic effect that begins to take place. It really makes no difference whether the words are ‘You are my God’ or ‘I am calm,’ the results are the same” (A Time of Departing, p. 150).

Catholic contemplative master Anthony de Mello agrees. He says:

“A Jesuit friend who loves to dabble in such things … assures me that, through constantly saying to himself ‘one-two-three-four’ rhythmically, he achieves the same mystical results that his more religious conferees claim to achieve through the devout and rhythmical recitation of some ejaculation. And I believe him” (Sadhana: A Way to God, pp. 33, 34).

Across from the reference to “silence” on page 14 of The Seven Day Journey we find the following photo on page 15 (pictured to the right):

I told myself that maybe I was being too paranoid and that this photo Merton took was just of an old wagon wheel and had nothing to do with Eastern meditative practices encapsulated in the Wheel of Life. So I told myself to give it a chance, so I put page 14 and 15 out of my mind. Okay. Page 16 mentions repeating words in a mantra, something Catholics are use to, even in light of Matthew 6:7. Again I put it aside. When I got to page 26 however, all these thoughts reemerged with this:

From then on Merton never stopped writing. Books, articles, poems, flowed from his pen. He wrote books of meditation, books about the monastic life, books on issues of peace and war, books on Zen and the east.[5]

My thoughts were back to that wheel. I remembered where I had seen it before — So I flipped the book closed and there on the cover was where that wheel sat (see photo above), confirming my thought that Merton truly believed what he said when he said “I see no contradiction between Buddhism and Christianity. I intend to become as good a Buddhist as I can.” Now I was back to my comparative religious mindset. Mind you it only took me 26-pages to resume this thinking. On page 32 (SDJw/TM) the Desert Fathers are mentioned, keep in mind that the progression of their practices and Merton’s lifting them up for modern consumption looks like this (pictured to the right):

This reference to the Desert Fathers in his Contemplative Prayer book and Esther de Waal mentioning that Merton loved the Desert Fathers (42) is troublesome to me. Loving the Desert Fathers is a “ding” in my book, especially considering the other biographies I put together (see: Part I, Part II, Part III). There are offensive theological and philosophical positions throughout SDJw/TM. However, I wanted to point out a big one or two that take an Eastern slant (there are positions in this book that fly in the face of Reformational thinking that undergirds Protestantism as well) — On pages 66 and 68 we find the following:

The meditation on the power of Christ continues as Merton now leads us more deeply into a rediscovery, a recognition of the Christ in the Trinity and in each one of us.

Christianity is life and wisdom in Christ,

It is a return to the Father in Christ.

It is a return to the infinite abyss of pure reality in which our own reality is grounded

and in which we exist.

It is a return to the source of all meaning and all truth.

It is a rediscovery of paradise within our own spirit, by self-forgetfulness.

And, because of our oneness with Christ,

It is the recognition of ourselves as sons and daughters of the Father. It is the recognition of ourselves as other Christs.

It is the awareness of strength and love imparted to us by the

miraculous presence of the Nameless and Hidden One

Whom we call the Holy Spirit.

[….]

Writing to the Zen scholar Daisetz Suzuki he speaks of Christ within:

about his own hidden spiritual life. Writing to the Zen scholar Daisetz Suzuki he speaks of the Christ within.

The Christ we seek is within us,

in our inmost self,

is our inmost self,

and yet infinitely transcends ourselves.

Christ himself is in us as unknown and unseen.

We follow Him,

we find Him,

and then He must vanish,

and we must go along without Him at our side. Why?

Because He is even closer than that.

He is ourself.

In case you didn’t catch it, those two quotes are very New Age’ish. There is a bit of universalism involved because this God-consciousness indwells all. De Waal tells a story Merton shared:

In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realisation that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers . . . Then it was as though I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality, the person that each one is in God’s eyes. If only they could see themselves as they really are.

She continues with a different quote, same page:

I have the immense joy of being man, a member of a race in which God Himself became incarnate. As if the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition could overwhelm me, now I realise what we all are. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.

Taken by itself of course, the above would be hard to make a case from. Taken as a whole however, it is pretty damning. I am not done however, I love this upcoming page. It made me wonder how pastors think of this page in light of all the evidence as a whole, especially conservative Reformed and Evangelical pastors. What contortions do they need to go through in order to make this philosophy fit with the inerrant Word of God. To me it must be mind-boggling! Feelings and emotions [e.g., these practices “make me feel good,” or, “give me the feeling of being closer to God.” Aside from feelings, how do they compare to the Word of God?] must be imported into the equation to ease over the obvious heresies involved. Here is page 88:

One way of seeing Merton’s life is as ‘an odyssey towards unity’. His path towards healing and maturity was one of unification. He faced the opposites and the tensions within himself, and let them converge. In doing this he becomes a symbol of the way in which we have watched in the twentieth century the bringing together of East and West, of masculine and feminine, secular and religious. Merton’s interest in the East has at times been controversial. ‘We must contain all divided worlds in ourselves’ he once said. He learnt much in his later years from the study of Eastern thought and in particular from Zen. He spent five years studying texts from fourth and fifth century Taoist circles. He was attracted to them because he found there ‘a certain taste for simplicity, for humility, self-effacement, silence and in general a refusal to take seriously the aggressivity, the ambition, the pusg, the self-importance which one must display in order to get along in society.’ He also discovered here the role played by the central pivot through which passed Yes and No, I and non-I. Here he found the complementarily of opposites, and this became extremely important for him.

We see it in the yin-yang symbol [actual symbol from book].

Here then are light/dark, good/evil, masculine/feminine. The white and the black show that contradiction exists, and yet each flows into the other. At the start of each there is a small portion of the other. Taken separately each side appears contradictory; taken as a whole they flow together and become one dynamic unity.

How this could be taken as “normative” in a Christian’s life is beyond me. A page later we find this, “It is not a question of either-or but of all-in-one… of wholeness, wholeheartedness and unity… which finds the same ground of love in everything.” Hogwash! A couple of pages later (93) we find this as well, “It is an invitation to become part of that dance, in harmony with the whole universe…” Last I remember, the universe isn’t in harmony (Romans 8:22). What is presented to us in this book is not Christian theology, it is a mix of paganism and Catholicism — both of which are works oriented. Man trying to spread the gap between God and himself. By-the-by, the forward to this book is by Henry Nouwen, another damning sign for those apologists who live by the Sword (Hebrews 4:12):

| For the word of God is living and effective and sharper than any double-edged sword, penetrating as far as the separation of soul and spirit, joints and marrow. It is able to judge the ideas and thoughts of the heart. ~ HCSB |

God means what he says. What he says goes. His powerful Word is sharp as a surgeon’s scalpel, cutting through everything, whether doubt or defense, laying us open to listen and obey. Nothing and no one is impervious to God’s Word. We can’t get away from it—no matter what. ~ The Message |

Footnotes:

[1] David Cloud, Contemplative Mysticism: A Powerful Ecumenical Bond (Port Huron, MI: Way of Life Literature, 2008), 85-89.

[2] (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 1982), 85.

[3] Thomas Merton, Contemplative Prayer (New York, NY: Image/Doubleday, 1996), 35-36.

[4] Cloud, 64-66

[5] Esther de Waal, A Seven Day Journey with Thomas Merton (Ann Arbor, MI: Charis, 1992).