MEDIA and W.W. ADDED

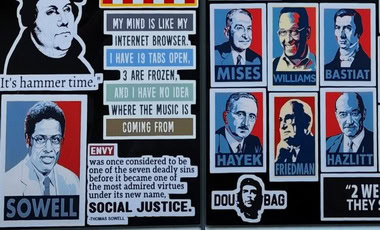

Often I am asked who the pictured persons are on the back of my van. So I figured I would explain a few of them in bio form and what books by them are classics.

All books and pictures will be linked.

(More at Econ Library) Milton Friedman was the twentieth century’s most prominent advocate of free markets. Born in 1912 to Jewish immigrants in New York City, he attended Rutgers University, where he earned his B.A. at the age of twenty. He went on to earn his M.A. from the University of Chicago in 1933 and his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1946. In 1951 Friedman received the John Bates Clark Medal honoring economists under age forty for outstanding achievement. In 1976 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics for “his achievements in the field of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory, and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.” Before that time he had served as an adviser to President Richard Nixon and was president of the American Economic Association in 1967. After retiring from the University of Chicago in 1977, Friedman became a senior research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

Friedman established himself in 1945 with Income from Independent Professional Practice, coauthored with Simon Kuznets. In it he argued that state licensing procedures limited entry into the medical profession, thereby allowing doctors to charge higher fees than they would be able to do if competition were more open.

His landmark 1957 work, A Theory of the Consumption Function, took on the Keynesian view that individuals and households adjust their expenditures on consumption to reflect their current income. Friedman showed that, instead, people’s annual consumption is a function of their “permanent income,” a term he introduced as a measure of the average income people expect over a few years.

In Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman wrote arguably the most important economics book of the 1960s, making a case for relatively free markets to a general audience. He argued for, among other things, a volunteer army, freely floating exchange rates, abolition of licensing of doctors, a negative income tax, and education vouchers. (Friedman was a passionate foe of the military draft: he once stated that the abolition of the draft was almost the only issue on which he had personally lobbied Congress.) Many of the young people who read it were encouraged to study economics themselves. His ideas spread worldwide with Free to Choose (coauthored with his wife, Rose Friedman), the best-selling nonfiction book of 1980, written to accompany a TV series on the Public Broadcasting System. This book made Milton Friedman a household name.

(More at Econ Library) If any twentieth-century economist was a Renaissance man, it was Friedrich Hayek. He made fundamental contributions in political theory, psychology, and economics. In a field in which the relevance of ideas often is eclipsed by expansions on an initial theory, many of his contributions are so remarkable that people still read them more than fifty years after they were written. Many graduate economics students today, for example, study his articles from the 1930s and 1940s on economics and knowledge, deriving insights that some of their elders in the economics profession still do not totally understand. It would not be surprising if a substantial minority of economists still read and learn from his articles in the year 2050. In his book Commanding Heights, Daniel Yergin called Hayek the “preeminent” economist of the last half of the twentieth century.

Hayek was the best-known advocate of what is now called Austrian economics. He was, in fact, the only major recent member of the Austrian school who was actually born and raised in Austria. After World War I, Hayek earned his doctorates in law and political science at the University of Vienna. Afterward he, together with other young economists Gottfried Haberler, Fritz Machlup, and Oskar Morgenstern, joined Ludwig von Mises’s private seminar—the Austrian equivalent of John Maynard Keynes’s “Cambridge Circus.” In 1927 Hayek became the director of the newly formed Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research. In the early 1930s, at the invitation of Lionel Robbins, he moved to the faculty of the London School of Economics, where he stayed for eighteen years. He became a British citizen in 1938.

Most of Hayek’s work from the 1920s through the 1930s was in the Austrian theory of business cycles, capital theory, and monetary theory. Hayek saw a connection among all three. The major problem for any economy, he argued, is how people’s actions are coordinated. He noticed, as Adam Smith had, that the price system—free markets—did a remarkable job of coordinating people’s actions, even though that coordination was not part of anyone’s intent. The market, said Hayek, was a spontaneous order. By spontaneous Hayek meant unplanned—the market was not designed by anyone but evolved slowly as the result of human actions. But the market does not work perfectly. What causes the market, asked Hayek, to fail to coordinate people’s plans, so that at times large numbers of people are unemployed?

One cause, he said, was increases in the money supply by the central bank. Such increases, he argued in Prices and Production, would drive down interest rates, making credit artificially cheap. Businessmen would then make capital investments that they would not have made had they understood that they were getting a distorted price signal from the credit market. But capital investments are not homogeneous. Long-term investments are more sensitive to interest rates than short-term ones, just as long-term bonds are more interest-sensitive than treasury bills. Therefore, he concluded, artificially low interest rates not only cause investment to be artificially high, but also cause “malinvestment”—too much investment in long-term projects relative to short-term ones, and the boom turns into a bust. Hayek saw the bust as a healthy and necessary readjustment. The way to avoid the busts, he argued, is to avoid the booms that cause them.

Hayek and Keynes were building their models of the world at the same time. They were familiar with each other’s views and battled over their differences. Most economists believe that Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) won the war. Hayek, until his dying day, never believed that, and neither do other members of the Austrian school. Hayek believed that Keynesian policies to combat unemployment would inevitably cause inflation, and that to keep unemployment low, the central bank would have to increase the money supply faster and faster, causing inflation to get higher and higher. Hayek’s thought, which he expressed as early as 1958, is now accepted by mainstream economists (see phillips curve).

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Hayek turned to the debate about whether socialist planning could work. He argued that it could not. The reason socialist economists thought central planning could work, argued Hayek, was that they thought planners could take the given economic data and allocate resources accordingly. But Hayek pointed out that the data are not “given.” The data do not exist, and cannot exist, in any one mind or small number of minds. Rather, each individual has knowledge about particular resources and potential opportunities for using these resources that a central planner can never have. The virtue of the free market, argued Hayek, is that it gives the maximum latitude for people to use information that only they have. In short, the market process generates the data. Without markets, data are almost nonexistent.

Mainstream economists and even many socialist economists (see socialism) now accept Hayek’s argument. Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs noted: “If you ask an economist where’s a good place to invest, which industries are going to grow, where the specialization is going to occur, the track record is pretty miserable. Economists don’t collect the on-the-ground information businessmen do. Every time Poland asks, Well, what are we going to be able to produce? I say I don’t know.”

In 1944 Hayek also attacked socialism from a very different angle. From his vantage point in Austria, Hayek had observed Germany very closely in the 1920s and early 1930s. After he moved to Britain, he noticed that many British socialists were advocating some of the same policies for government control of people’s lives that he had seen advocated in Germany in the 1920s. He had also seen that the Nazis really were National Socialists; that is, they were nationalists and socialists. So Hayek wrote The Road to Serfdom to warn his fellow British citizens of the dangers of socialism. His basic argument was that government control of our economic lives amounts to totalitarianism. “Economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest,” he wrote, “it is the control of the means for all our ends.”

To the surprise of some, John Maynard Keynes praised the book highly. On the book’s cover, Keynes is quoted as saying: “In my opinion it is a grand book…. Morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it; and not only in agreement with it, but in deeply moved agreement.”

Although Hayek had intended The Road to Serfdom only for a British audience, it also sold well in the United States. Indeed, Reader’s Digest condensed it. With that book Hayek established himself as the world’s leading classical liberal; today he would be called a libertarian or market liberal. A few years later, along with Milton Friedman, George Stigler, and others, he formed the Mont Pelerin Society so that classical liberals could meet every two years and give each other moral support in what appeared to be a losing cause. …

(More at Famous Economists) Thomas Sowell is a renowned economist, theorist and writer hailing from the United States of America. He is known for his old-fashioned assessments of economic theory, often drawing criticism from his liberal counterparts, but still attracting appreciation from fellow conservatives for encouraging hard work and self-sufficiency.

Sowell is an African American born in North Carolina on 30 June, 1930. He spent a lot of his early childhood migrating between cities due to family issues which required him to drop out of his high school. His family’s financial predicament forced him to work different jobs at a very young age; his endeavors saw him work at a machine shop and as a delivery boy for Western Union. He was soon inducted in to the Marine Corps as an aspiring photographer, where he also learned how to operate pistols. He managed this job whilst simultaneously continuing his education, attending night classes at his high school.

After enrolling in Howard University, Sowell soon obtained a transfer to Harvard University on the back of impressive results in College Board examinations and positive recommendations from professors. Sowell graduated with a degree in economics in 1958, and then moved to Columbia University for his Masters program, after which he completed is Ph.D. studies from the University of Chicago in 1968.

TRANSCRIPT

Dave Rubin: You were a Marxist at one time in your life. Most people will find this hard to believe, but, It is true.

Thomas Sowell: But it’s not that unusual. Ahhh, most of the leading conservative thinkers around time did not start off as conservatives. You had a couple like Bill Buckley and George Will [that did start off conservative]. But, Milton Friedman was a liberal and a Keynesian. Hayek was a socialist. Ronald Reagan was so far left at one point the FBI was following him.

Dave Rubin: So then, what was your wake up to what was wrong with that line of thinking?

Thomas Sowell: Facts

PICTURED: Thomas Sowell’s book on Marxist Economics, David Horowitz, Whittaker Chambers, Frank Meyer, William F. Buckley Jr., George Will, Milton Friedman, F.A. Hayek, Ronald Reagan

Thomas Sowell occupied a number of teaching positions at various universities after completing his education. After teaching at Rutgers and Howard universities in the early 60’s, he held the title of assistant professor of economics at Cornell and the University of California, Los Angeles where he was given full professor status in 1974. Sowell has also been part of the faculty at Brandeis University and Amherst College. In 1980, he moved to Stanford University which granted him the title of Senior Fellow at its Hoover Institution. He has held this position there ever since.

Sowell initially subscribed to the Marxist school of thought in economics theory, an approach he renounced after his experience working as an intern for the U.S. Department of Labor in 1960, instead opting for free market principles. His research in his time there also made him critical of minimum wage laws, which he felt not only perpetuated unemployment, but were introduced by bureaucrats only to secure their status in the government. He orchestrated the Black Alternatives Conference in San Francisco during the Reegan regime to oppose minimum wages and call for more black representation in the government. In 1969 however, Sowell defended Cornell University against allegations of racism after observing the rebellion by black students.

Sowell also boasts remarkable credentials in the field or journalism and writing, expressing opinion on a multitude of topics such as state policies on social and racial groups, Marxist economic theory and education. He has published a number of works since 1971, with some of his best-selling books being ‘Basic Economics: A Common Sense Guide to the Economy‘, ‘Black Rednecks and White Liberals‘, and ‘Intellectuals and Society‘. Besides publishing books Sowell has written for prominent magazines and academic journals. These include the New York Times, Forbes and the Spectator. He also managed a column for the Scripps-Howard news service in the years 1984-1990.

During is elaborate career, Thomas Sowell was no stranger to controversy. His claims that inequality which persists across ethnic groups bears no connection with discrimination, but is to do with the characteristics and attitudes intrinsic to these groups was not received well by some sects. His resistance towards government assistance of economically and socially challenged groups, which he believes discourages self-sufficiency and dependence, has also been criticized. But he still remains one of the great African American thinkers of his generation given his contributions not only towards the economics, but political philosophy and social theory as well. …

Ludwig von Mises was one of the last members of the original austrian school of economics. He earned his doctorate in law and economics from the University of Vienna in 1906. One of his best works, The Theory of Money and Credit, was published in 1912 and was used as a money and banking textbook for the next two decades. In it Mises extended Austrian marginal utility theory to money, which, noted Mises, is demanded for its usefulness in purchasing other goods rather than for its own sake.

In that same book Mises also argued that business cycles are caused by the uncontrolled expansion of bank credit. In 1926 Mises founded the Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research. His most influential student, Friedrich Hayek, later developed Mises’s business cycle theories.

Another of Mises’s notable contributions is his claim that socialism must fail economically. In a 1920 article, Mises argued that a socialist government could not make the economic calculations required to organize a complex economy efficiently. Although socialist economists Oskar Lange and Abba Lerner disagreed with him, modern economists agree that Mises’s argument, combined with Hayek’s elaboration of it, is correct (see socialism).

Mises believed that economic truths are derived from self-evident axioms and cannot be empirically tested. He laid out his view in his magnum opus, Human Action, and in other publications, although he failed to persuade many economists outside the Austrian school. Mises was also a strong proponent of laissez-faire; he advocated that the government not intervene anywhere in the economy. Interestingly, though, even Mises made some striking exceptions to this view. For example, he believed that military conscription could be justified in wartime.

From 1913 to 1934 Mises was an unpaid professor at the University of Vienna while working as an economist for the Vienna Chamber of Commerce, in which capacity he served as the principal economic adviser to the Austrian government. To avoid the Nazi influence in his Austrian homeland, in 1934 Mises left for Geneva, where he was a professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies until he emigrated to New York City in 1940. He was a visiting professor at New York University from 1945 until he retired in 1969.

Mises’s ideas—on economic reasoning and on economic policy—were out of fashion during the Keynesian revolution that took over American economic thinking from the mid-1930s to the 1960s. Mises’s upset at the Keynesian revolution and at Hitler’s earlier destruction of his homeland made Mises bitter from the late 1940s on. The contrast between his early view of himself as a mainstream member of his profession and his later view of himself as an outcast shows up starkly in The Theory of Money and Credit. The first section, written in 1912, is calmly argued; the last section, added in the 1940s, is strident. ….

Joseph Schumpeter described Bastiat nearly a century after his death as “the most brilliant economic journalist who ever lived.” Orphaned at the age of nine, Bastiat tried his hand at commerce, farming, and insurance sales. In 1825, after he inherited his grandfather’s estate, he quit working, established a discussion group, and read widely in economics.

Bastiat made no original contribution to economics, if we use “contribution” the way most economists use it. That is, we cannot associate one law, theorem, or pathbreaking empirical study with his name. But in a broader sense Bastiat made a big contribution: his fresh and witty expressions of economic truths made them so understandable and compelling that the truths became hard to ignore.

Bastiat was supremely effective at popularizing free-market economics. When he learned of Richard Cobden’s campaign against the British Corn Laws (restrictions on the import of wheat, barley, rye, and oats), Bastiat vowed to become the “French Cobden.” He subsequently published a series of articles attacking protectionism that brought him instant acclaim. In 1846 he established the Association of Free Trade in Paris and his own weekly newspaper, in which he waged a witty assault against socialists and protectionists.

Bastiat’s “A Petition,” usually referred to now as “The Petition of the Candlemakers,” displays his rhetorical skill and rakish tone, as this excerpt illustrates:

We are suffering from the ruinous competition of a foreign rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light, that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price…. This rival … is none other than the sun….

We ask you to be so good as to pass a law requiring the closing of all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains, casements, bull’s-eyes, deadlights and blinds; in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures.

This reductio ad absurdum of protectionism was so effective that one of the most successful postwar economics textbooks, Economics by Paul A. Samuelson, quotes the candlemakers’ petition at the head of the chapter on protectionism.

Bastiat also emphasized the unintended consequences of government policy (he called them the “unseen” consequences). Friedrich Hayek credits Bastiat with this important insight: if we judge economic policy solely by its immediate effects, we will miss all of its unintended and longer-run effects and will undermine economic freedom, which delivers benefits that are not part of anyone’s conscious design. Much of Hayek’s work, and some of Milton Friedman’s, was an exploration and elaboration of this insight.

Henry Hazlitt, a journalist, writer, and economist, was born in Philadelphia. His father died soon after his birth, and he attended a school for poor, fatherless boys. His mother remarried, and the family moved to Brooklyn, New York. When he graduated from high school, Hazlitt’s ambition was to go to Harvard and write books on philosophy. But his stepfather died, and he started attending the no-tuition College of the City of New York. However, he soon left school to support himself and his mother. In those years, it was not hard for a young man to get a job. With no government- imposed obstacles to hiring or firing, no minimum wage laws, no workday or workweek restrictions, and no unemployment or social security taxes, employer and potential employee needed only to agree on the terms of employment. If things did not work out, the employee could quit or be fired. Hazlitt’s first jobs lasted only a few days each.

When Hazlitt realized that with shorthand and typing skills he could earn two or three times the $5 per week he was being paid as an unskilled office boy, he studied stenography. Determined to become a writer, he looked for a newspaper job and soon took a job with the Wall Street Journal, then a small limited-circulation publication. Its executives dictated editorials to him, and reporters phoned in their stories. At first he knew nothing about Wall Street. On one assignment, Hazlitt was informed that a company had passed its dividend. Hazlitt thought this meant the company had approved it. But in stock market terminology, passing a dividend meant skipping it. Fortunately, in reporting the story, Hazlitt used the company’s original verb. He was learning about the market.

Having missed out on college, Hazlitt determined to study on his own. He started reading college economics texts, but was not misled by their anticapitalist flavor. Experience had taught him that businessmen did not always earn profits; they sometimes suffered losses. Hazlitt’s uncle had been forced to close his Coney Island enterprise when it rained heavily over a Fourth of July holiday and customers stayed away in droves. Hazlitt’s stepfather lost his business making children’s hats when this custom went out of fashion.

Hazlitt’s real economic education began with his study of Philip H. Wicksteed’s The Common Sense of Political Economy, which introduced him to the subjective theory of value, only recently developed by Austrian economists Carl Menger and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. Hazlitt continued his self-study program and persisted in his ambition to write. His first book, Thinking as a Science, appeared in 1916 before his 22nd birthday.

In 1916, Hazlitt left the Wall Street Journal for the New York Evening Post. He was forced to leave during World War I, serving in the Army Air Corps in Texas. However, when the war ended, the Post wired Hazlitt that he could have his job back if he was in the office in 5 days. He entrained immediately, went directly to the newspaper, and worked that day in uniform.

From the Post, Hazlitt went on to become either financial or literary editor of various New York papers. From 1934 to 1946, Hazlitt was an editorial writer for The New York Times. Hazlitt and the Times parted company over the Bretton Woods Agreement, against which Hazlitt had been editorializing. The Times supported the agreement, which had been endorsed by 43 nations, but Hazlitt claimed it would only lead to monetary expansion and refused to support it. Hazlitt secured a position with Newsweek and left the Times. From 1946 to 1966, he wrote Newsweek’s Business Tides column.

An analysis of Hazlitt’s libertarian sympathies must mention his association with Ludwig von Mises, the leading exponent of the Austrian School of Economics. Hazlitt first heard of Mises through Benjamin M. Anderson’s The Value of Money, published in 1917. Anderson criticized many writers on monetary theory, but said he found in Mises’s works “very noteworthy clarity and power. His Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel [later translated into English as The Theory of Money and Credit] is an exceptionally excellent book.” Although Mises had been widely respected in Europe, he was little known in this country when he arrived as a wartime refugee in 1940. When Mises’s Socialism appeared in English in 1937, Hazlitt remembered Anderson’s remark about Mises and reviewed Socialism in the Times, describing it as “the most devastating analysis of socialism yet penned … an economic classic in our time.” He sent his review to Mises in Switzerland and, 2 years later, when Mises came to this country, he phoned Hazlitt. Hazlitt recalled Mises’s call as if coming from an economic ghost of centuries past. Hazlitt and Mises soon met and became close friends. Hazlitt’s contacts helped establish Mises on this side of the Atlantic, enabling him to continue his free-market teaching, writing and lecturing. Hazlitt was instrumental in persuading Yale University to publish Mises’s Omnipotent Government and Bureaucracy in 1944 and then his major opus, Human Action, in 1949. As a founding trustee of the FEE, Hazlitt also was responsible for Mises’s appointment as economic advisor to that Foundation.

In 1946, Hazlitt wrote and published his most popular book, Economics in One Lesson. It became a best-seller, was translated into 10 languages, and still sells thousands of copies each year. Its theme—that economists should consider not only the seen but also the unseen consequences of any government action or policy—was adopted from 19th-century free-market economist Frédéric Bastiat. Thanks to Economics in One Lesson’s short chapters and clear, lucid style, countless readers were able to grasp its thesis that government intervention fails to attain its hoped-for objectives.

While still at Newsweek, Hazlitt edited the libertarian biweekly, The Freeman—as coeditor from 1950 to 1952 and as editor-in-chief from 1952 to 1953. When the left-liberal Washington Post bought Newsweek, Hazlitt became a columnist from 1966 to 1969 for the international Los Angeles Times syndicate. ….

Walter E. Williams, prominent economist, commentator, and professor at George Mason University, died on Tuesday, December 1. He was 84.

Williams was a national fellow at the Hoover Institution in the academic year 1975-1976. He also served on the Board of Overseers from 1983 to 2004 and was a member of its executive committee from 1994 to 2004.

The highly esteemed Williams was born in 1936 to humble origins in Philadelphia. A onetime taxi driver, he went on to earn a BA in economics from California State University (Cal State)– Los Angeles, and an MA and PhD in economics from University of California, Los Angeles.

He has served on the economic faculties of Los Angeles City College, Cal State Los Angeles, Temple University, and Grove City (Pennsylvania) College. Since 1980, he has been the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor at George Mason University (GMU), Fairfax, Virginia, where he was also the chair of the economics department from 1995 to 2001.

“The economics profession boasts many excellent, but it has precious few with the ability and interest to do rigorous research and to engage the public with its results,” said Donald J. Boudreaux, Williams’s GMU colleague, in Wall Street Journal tribute.

A prolific writer of widely read syndicated columns, academic papers, and best-selling books, Williams authored the seminal 1982 book The State against Blacks, about how the regulatory state negatively impacts African Americans. He was also known for his concise arguments about how minimum-wage laws can result in employment discrimination.

“What minimum-wage laws do is lower the cost of, and hence subsidize, racial preference indulgence. After all, if an employer must pay the same wage no matter whom he hires, the cost of discriminating in favor of the people he prefers is cheaper,” Williams held.

Williams has also made countless appearances on radio and television shows including Firing Line, Free to Choose, Face the Nation, and Crossfire. In 2014, he produced Suffer No Fools, a PBS documentary criticizing antipoverty programs and based on his autobiography, Up from the Projects, published in 2010 by Hoover Institution Press. Among his other thirteen books are More Liberty Means Less Government, also published by Hoover Institution Press in 1999. The collection of thoughtful, hard-hitting essays explores issues including minimum wage, the Americans with Disabilities Act, affirmative action, and racial and gender quotas.

Williams was also a perennial substitute host of The Rush Limbaugh Show, on which he would frequently invite Milton and Rose Friedman Senior Fellow Thomas Sowell for conversations on economics, politics, and a wide range of contemporary social issues.

“He was my best friend for half a century. There was no one I trusted more or whose integrity I respected more,” Sowell said.

I Hope This Helps!

The conservative base of the Republican Party are filled with people like me and all the peeps I know. We are well read, present answers to questions with facts. Correct peoples opinions with a more reality based view. Etc. The books above [and more] helped form my opinions on economics and government, and assisted in a total worldview. A coherent worldview must be able to satisfactorily answer four questions: that of origin, meaning, morality, and destiny. All those are based in the Christian worldview and have a more coherent view within the Biblical, Judeo-Christian worldview. Meaning and direction in life are salted with the laws of economics and self governance. And church history plays a role in all this. Just one example:

A WILDERNESS OF CASUISTRY

In 1957, the great Reformation historian Johannes Heckel called Luther’s two-kingdoms theory a veritable Irrgarten, literally “garden of errors,” where the wheats and tares of interpretation had grown indiscriminately together. Some half a century of scholarship later, Heckel’s little garden of errors has become a whole wilderness of confusion, with many thorny thickets of casuistry to ensnare the unsuspecting. It is tempting to find another way into Lutheran contributions to legal theory. But Luther’s two-kingdoms theory was the framework on which both he and many of his followers built their enduring views of law and authority, justice and equity, society and politics. We must wander in this wilderness at least long enough to get our legal bearings.

Luther was a master of the dialectic — of holding two doctrinal opposites in tension and of exploring ingeniously the intellectual power of this tension. Many of his favorite dialectics were set out in the Bible and well rehearsed in the Christian tradition: spirit and flesh, soul and body, faith and works, heaven and hell, grace and nature, the kingdom of God versus the kingdom of Satan, the things that are God’s and the things that are Caesar’s, and more. Some of the dialectics were more uniquely Lutheran in accent: Law and Gospel, sinner and saint, servant and lord, inner man and outer man, passive justice and active justice, alien righteousness and proper righteousness, civil uses and theological uses of the law, among others.

Luther developed a good number of these dialectical doctrines separately in his writings from 1515 to 1545 — at different paces, in varying levels of detail, and with uneven attention to how one doctrine fit with others. He and his followers eventually jostled together several doctrines under the broad umbrella of the two-kingdoms theory. This theory came to describe at once: (I) the distinctions between the fallen realm and the redeemed realm, the City of Man and the City of God, the Reign of the Devil and the Reign of Christ; (2) the distinctions between the sinner and the saint, the flesh and the spirit, the inner man and the outer man; (3) the distinctions between the visible Church and the invisible Church, the Church as governed by civil law and the Church as governed by the Holy Spirit; (4) the distinctions between reason and faith, natural knowledge and spiritual knowledge; and (5) the distinctions between two kinds of righteousness, two kinds of justice, two uses of law.

When Luther, and especially his followers, used the two-kingdoms terminology, they often had one or two of these distinctions primarily in mind, sometimes without clearly specifying which. Rarely did all of these distinctions come in for a fully differentiated and systematic discussion and application, especially when the jurists later invoked the two-kingdoms theory as part of their jurisprudential reflections. The matter was complicated even further because both Anabaptists and Calvinists of the day eventually adopted and adapted the language of the two kingdoms as well — each with their own confessional accents and legal applications that were sometimes in sharp tension with Luther’s and other Evangelical views. It is thus worth spelling out Luther’s understanding of the two kingdoms in some detail, and then drawing out its implications for law, society, and politics.

John Witte, Jr., Law and Protestantism: The Legal Teachings of the Lutheran Reformation (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 94-95.

iPencil

Starring comedian Andrew Heaton, EconPop takes a surprisingly deep look at the economic themes running through classic films, new releases, TV shows and more from the best of pop culture and entertainment. Heaton brings a unique mix of dry wit and whimsy to bear on the dismal science of economics and the result is always entertaining, educational and irreverent. It’s Econ 101 meets At The Movies, with a dash of Monty Python.

I, Pencil

I, Pencil – FINAL CUT from Nicholas Tucker on Vimeo.

The “Original ‘I-Pencil'”