John Eastman in THE NEW YORK TIMES:

…“Subject to the jurisdiction” means more than simply being present in the United States. When the 14th Amendment was being debated in the Senate, Senator Lyman Trumbull, a key figure in its drafting and adoption, stated that “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States meant not “owing allegiance to anybody else.”

And Senator Jacob Howard, who introduced the language of the clause on the floor of the Senate, contended that it should be interpreted in the same way as the requirement of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, which afforded citizenship to “all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power.”

The Supreme Court has never held otherwise. Some advocates for illegal immigrants point to the 1898 case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark, but that case merely held that a child born on U.S. soil to parents who were lawful, permanent (legally, “domiciled”) residents was a citizen.

The broader language in the case suggesting that birth on U.S. soil is alone sufficient (thereby rendering the “subject to the jurisdiction” clause meaningless) is only dicta — not binding. The court did not specifically consider whether those born to parents who were in the United States unlawfully were automatically citizens.

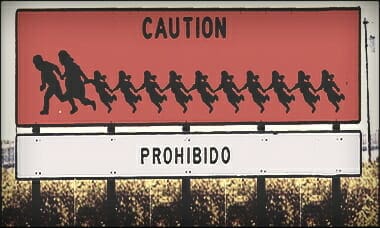

The misunderstood policy of birthright citizenship provides a powerful magnet for people to violate our immigration laws and undermines the plenary power over naturalization that the Constitution explicitly gives to Congress. It is long past time to clarify that the 14th Amendment does not grant U.S. citizenship to the children of anyone just because they can manage to give birth on U.S. soil.

Here is part of the NATIONAL REVIEW article by Andrew McCarthy:

…My friend John Eastman explained why the 14th Amendment does not mandate birthright citizenship in this 2015 New York Times op-ed. In a nutshell, the Amendment states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The highlighted term, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was understood at the time of adoption to mean not owing allegiance to any other sovereign. To take the obvious example, if a child is born in France to a married couple who are both American citizens, the child is an American citizen.

I won’t rehash the arguments on both sides. With due respect to our friend Dan McLaughlin (see here), I think Professor Eastman has the better of the argument. As I have observed before, and as we editorialized when Donald Trump was a candidate (here), this is a very charged issue, and it is entirely foreseeable that the Supreme Court (to say nothing of the lower federal courts teeming with Obama appointees) would construe the term jurisdiction differently from what it meant when the 14th Amendment was ratified….