The WALL STREET JOURNAL hurts itself closing article this good and important to the current dialogue surrounding this topic. Here is Daniel’s article:

We’ve arrived at a moment when some choices have to be made. After a lifetime watching America’s three main professional sports—baseball, football and basketball—I’ve decided I prefer baseball.

Starting Tuesday, I’ll exclusively devote what’s left of my sports-viewing budget to the Major League Baseball playoffs. And not just in the hope that my hometown Cleveland Indians will overcome last year’s heartbreaking loss for the ages to the Chicago Cubs.

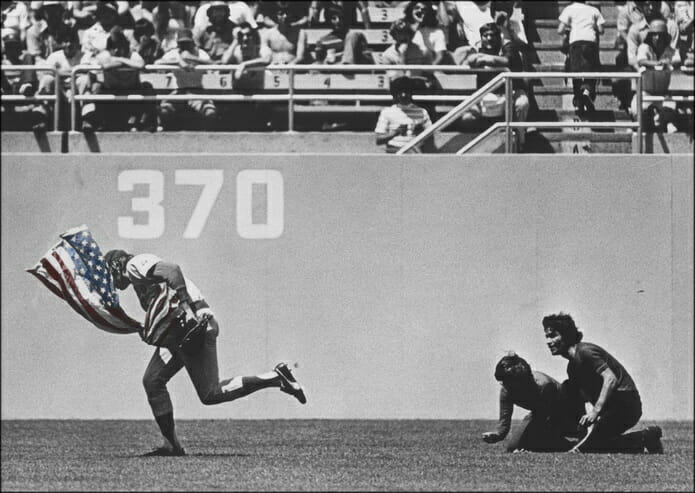

Set to one side that the reason most Americans can sing the words to their national anthem is that for generations, every American attending a professional baseball game has stood to look at the flag while someone sings “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Many Americans think the last words of the national anthem are “Play ball!”

Baseball is about baseball. The NFL and NBA seem to be about more things than I can process—some of them political, some of them personal.

Baseball has an informal code of on-field conduct, which has held for a hundred years. The NFL doesn’t seem to have an enforceable code of anything.

Last Sunday, after the New York Giants’ wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr. caught a touchdown pass, Mr. Beckham got down in the end zone and imitated a dog urinating on a fire hydrant, which the opposing Philadelphia Eagles (who won) took as mockery of their team.

From Babe Ruth 90 years ago to Aaron Judge now, when you hit a home run, you run around the bases and into the dugout. That’s it. No end-zone antics that suggest the sport itself takes a back seat to a personality.

After the Yankees’ Mr. Judge hit his 50th home run this week, a record for a rookie, his teammates had to force him out of the dugout to wave to the cheering crowd.

For some years, the parsons of the sports press have pushed the idea that demonstrations of high-level athletic skill, the result of uncountable hours of practice, were morally insufficient. Athletes, the parsons intoned, had to “give back” by dedicating their status to solving the nation’s endlessly unresolved issues of race, gender and—the inevitable guilt trip they laid on pro athletes—income inequality.

And so last September, Colin Kaepernick, the San Francisco 49ers backup quarterback, reduced the parsonage’s moralistic hectoring of professional athletes to its absurd end by deciding that the pregame national anthem was the place to raise the issue of inner-city policing.

Only the innocent could feign shock that eventually Donald Trump, in his capacity as president of the United States, would go after the kneeling players about the same way you’d hear from a guy sitting in the high seats at a New York Jets game, who by the third quarter is on fumes: “Get that son of a bitch off the field!”

Stepping down to the Trumpian moment, LeBron James tweeted, “U bum!”

Sportswriters sometimes use the phrase “lunch bucket” about a player who is mainly interested in doing his job well without drawing attention to himself. Other than someone like Kawhi Leonard of the San Antonio Spurs, you don’t see too many stars in the NFL or NBA described as lunch-bucket guys anymore.

Most future stars of basketball and football are identified while they’re in high school. They often play in special leagues and receive constant visits from coaches at Division I universities.

Once inside the university, these players live and practice in gold-plated facilities. They play on national TV and are talked about nonstop by analysts and the political commentators at ESPN. They get famous young. (Though let it be said, 90% of the non-sports NFL and NBA news was made by maybe 10% of the players, until now.)

The road up in baseball is different. Promising teenagers go from high school into baseball’s minor leagues. They play for teams in places like Delmarva, Clinton and Greenville. They travel by bus and play before crowds not much bigger than what they had in Little League. They rise from A ball to AA (say, the Trenton Thunder) then AAA teams, which are in places most people have heard of, like Toledo, Fresno or El Paso.

Years spent competing and surviving against other skilled players teaches them they have to learn to be a member of a team before anyone calls them a star.

Some might say baseball isn’t political because so many players are from Latin America. But maybe the Latin players are mostly bemused at what the U.S. considers social problems, compared with escaping from Cuba across shark-infested waters or getting out of a dirt-road slum in Nicaragua or the Dominican Republic.

There is an expression in sports: Don’t leave it in the locker room. It means you are supposed to save your best performance for the game. With baseball, that’s still what you get.

We live in a highly polarized country. If people want their sport and its performers to be an affirmation of their politics, feel free. I don’t.